The 21st century will be a century of cities. Long the engines of American innovation, cities are supplying fresh ideas and vital economic growth, and in an interconnected world, they are working collaboratively across national boundaries to deal with big issues like economic development, environmental sustainability, and terrorism. Cities can lead America into the 21st century. But to do so, they need an infrastructure capable of serving as a platform for sustainable development. And they need an infrastructure that serves everyone.

Investing in urban infrastructure should be a top priority for the next president. As the White House lays out a vision for the future of our cities, it should keep in mind three lessons of history:

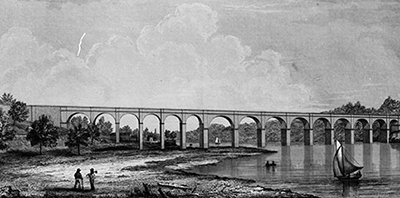

The growth of early U.S. cities was limited by the scarcity of clean drinking water. In 1837, New York City used the Croton Aqueduct to bring bring fresh water from Westchester County into the city.

To appreciate how American cities are built on infrastructure, consider public water systems. Until the mid-19th century, clean drinking water was scarce and sewer systems nonexistent; widespread contamination contributed to frequent outbreaks of disease, and the scarcity of water made it difficult to douse fires—a major scourge of early American cities. In 1837, following outbreaks of yellow fever and cholera and the Great Fire of 1835, New York City reached into rural Westchester County to collect fresh water via the Croton Aqueduct. Other big cities followed suit. Complex systems of reservoirs, aqueducts, filtration facilities, tunnels, and pipes helped big cities overcome key barriers to urban development—contamination, epidemic disease, and fire. Water infrastructure has become such a fundamental part of American life that we seldom think about it—until it fails us. The ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan, which is playing out in less spectacular fashion in other cities across the nation, highlights just how essential infrastructure is to urban life.

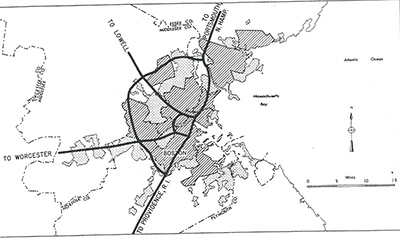

But if infrastructure has made the modern city possible, it has also contributed to some of the most severe problems facing American cities today. After World War II, massive federal investment in highways helped many white middle-class Americans—and many businesses—to move out of cities into surrounding metropolitan regions, leaving behind a legacy of racial segmentation, inner-city disinvestment, and the fragmentation of metropolitan regions. The same interstate highways that helped drive national economic growth in the late 1950s tore through working-class urban neighborhoods, displacing hundreds of thousands of residents and countless small businesses and subjecting those who stayed to environmental degradation. The challenges facing many American cities today are in no small measure the consequences of patterns of metropolitan development underpinned by automobile-centric infrastructure.

This 1955 "Yellow Book" of Interstate Highway System plans shows the city of Boston, Massachusetts, and illustrates the ways in which highways cut through urban neighborhoods.

Infrastructure has played a crucial—yet problematic—role in the making, and remaking, of the modern American city. Public works have expanded access to essential goods and to economic opportunities, and they have contributed to universal improvements in the standard of living. But they have also conferred advantages on privileged parts of American society at the expense of the marginalized. The story of urban water systems highlights the extent to which we are living off the legacy of the age of city building that ran from the mid-19th to the mid-20th century. If our cities are truly to thrive, we need to make our own investments in the future. And we need to do so in ways that serve all our citizens.

During the Great Depression, the federal government began to collaborate with cities to develop urban infrastructure through programs such as the Public Works Administration.

Prior to the 1930s, most infrastructure projects within cities were carried out by local governments. (Washington and the states helped to link localities through interregional transportation and the postal service.) Initially, municipalities used tools such as franchise grants, special assessments, and eminent domain to work collaboratively with private investors. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, cities developed an impressive capacity to plan, finance, and carry out projects themselves; after World War I, new public-benefit corporations took over some of these functions. Cities built roads, bridges, tunnels, water systems, electrical grids, and mass transit systems—all with relatively little help from the federal government.

Only during the Great Depression did the federal government and cities begin to collaborate in the development of urban infrastructure. In 1933, Congress and President Franklin Roosevelt created the Public Works Administration (PWA), which offered local governments grants-in-aid for large, capital-intensive construction projects; two years later, FDR established the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which paid unemployed Americans to work on projects designed by local governments.

The success of both initiatives depended on the capacity and the imagination of both local and national officials; working together, cities and the federal government could do things that neither was capable of on its own. “We would have been awful damned fools,” WPA director Harry Hopkins remarked, “if we thought for a minute that we have either the power or the ability to go out and set up 100,000 work projects . . . without the complete cooperation of local and state officials. We couldn’t do it if we wanted to.” For enterprising local leaders (such as New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia), the New Deal represented, as one official put it, “a challenge and an opportunity . . . to have done those things which make our cit[ies] more beautiful and useful, and which [we] on [our] own behalf would hardly ever be financially able to do.” In the span of a few years, the PWA and WPA helped build a staggering amount of infrastructure: airports, bridges, tunnels, subway extensions, parkways, schools, public beaches, college campuses, health centers, and public radio broadcast facilities.

The growth of suburban neighborhoods drained older cities of residents and revenue.

The initiatives of the 1930s established a new model of collaboration between the federal government and local authorities. In the postwar years, Congress replaced the New Deal agencies with a variety of targeted grant-in-aid programs (notably, to support the construction of hospitals and airports). The federal government also took on the role of supporting the nation’s water systems through regulation, quality assurance, and assistance, and, in the 1960s, it began to support the development of mass transit.

At its best, midcentury liberalism strengthened urban neighborhoods by building a social infrastructure that made city life more decent and enjoyable. But some elements of the New Deal’s vision were also at odds with the very form of the dense, crowded industrial city. Starting in the 1930s, the federal government actively supported suburban single-family homeownership, and Cold War spending on research and development funneled resources to new research complexes located on the outskirts of cities, such as Boston’s Route 128 and the Bay Area’s Silicon Valley. As suburbanization and corporate relocation drained older cities of residents and revenue, the federal government used infrastructure spending to try and help cities beat suburbia at its own game. New urban superhighways connected downtowns to outlying residential areas, and federally supported “urban renewal” projects flattened urban neighborhoods to create space for middle-class housing, commercial establishments, and third-sector institutions such as hospitals, university campuses, and cultural facilities. These projects offered little to established neighborhoods and their residents; indeed, inner-city communities paid the price for urban renewal, in the form of dislocation and environmental degradation. Planners also frequently routed new highways through communities of color, and they not infrequently used infrastructure to reinforce boundaries between white and nonwhite communities.

Cities have found it hard to maintain existing infrastructure. In 2014, Vice President Joe Biden likened La Guardia Airport in New York to "some third-world country."

Since the 1960s, public investment has largely been on the decline. Citizens responded to the excesses and inequities of urban renewal with intense protests, leading to more-rigorous permitting and approval processes. At the same time, suburbanization and corporate relocation made it harder for city governments to fund essential projects (while also prompting them to chase private investment for sports stadiums, convention centers, and other commercial facilities). Total public spending on transportation and water infrastructure topped out in the first half of the 1960s (as a share of GDP); it has been falling more or less ever since, although it revived temporarily following passage of the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Both federal spending on infrastructure and federal contributions to cities have declined sharply since the end of the 1970s.

The ongoing water crisis in Flint, Michigan, where the lack of clean water has poisoned thousands of children, is a vivid illustration of the consequences of neglecting the country's infrastructure.

Increasingly, cities have found it difficult to maintain existing infrastructure, let alone build new projects. Cities like New York, once the showcase of the New Deal, have crumbled. When La Guardia Airport opened in 1939, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia wrote ebulliently to President Roosevelt, thanking him for helping to build “the greatest, the best, the most up to date, and the most perfect airport in the United States . . . ‘the’ airport of the New World.” In 2014, Vice President Joe Biden made headlines when he likened La Guardia Airport to “some third-world country.” And New York, a hub of the global economy, has been a comparative urban success story. Cities like Flint, Michigan, have not been so fortunate.

Fortunately, infrastructure is the rare issue that today commands bipartisan support. “We’ve spent $4 trillion trying to topple various people,” Republican nominee Donald Trump remarked in a primary debate. “If we could’ve spent that $4 trillion in the United States to fix our roads, our bridges and all of the other problems . . . we would’ve been a lot better off.” Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton promised to fill America’s “infrastructure gap” through a five-year, $275 billion federal commitment. In a global economy, infrastructure is essential for economic competitiveness. It is also a matter of national prestige, as an outdated physical plant feeds a sense of national malaise. And catastrophes like the Flint water crisis, in which thousands of children have been poisoned, bring home just how much is at stake.

It is obvious that infrastructure needs to be a national priority. What does the history of city building tell us about how to approach the challenge of urban infrastructure?

Infrastructure sometimes seems like a highly technical issue—a question of engineering specifications, debt-amortization tables, obscure funding streams and review processes. But once one understands the history of our cities, it becomes clear that questions about infrastructure are really questions about what kinds of communities we want to live in. Do we value commercial activity above all, or do we want to commit some resources to non-commercial goods? How committed are we to the idea of a commonwealth, an infrastructure that connects everyone to basic resources and opportunities? How do we balance the long-range needs of our cities against our citizens’ right to have a say in what happens to their communities? Who gets to decide the future of our cities?

Tackling questions like these requires vision and leadership. Supplying that vision and leadership, above all, is the next president’s task.