The Miller Center hosted a First Year event, “A new dialogue on race in America.”

Donald Trump’s presidency offers an extraordinary opportunity to advance the paralyzed national discourse on race in America, and our new chief executive can validate his campaign claims to be a racially tolerant figure working for the success of all Americans—without alienating his core supporters.

To millions of citizens, that will sound like an astounding assertion. Many Americans concerned about racial issues, immigration, and discrimination regarded Trump’s election as a bleak setback, reversing 50 years of racial progress since the era of the civil rights movement.

Last November, Trump received negligible support from African American voters, who recoiled at revelations of racial discrimination by his family’s New York real estate company in the 1970s, a history of coarse public comments about African Americans, caustic statements during the campaign about Mexican immigrants and Muslims, and political endorsements from white supremacist organizations and their leaders.

When the Trump administration issued an executive order that blocked citizens of seven countries from entering the United States, it confirmed the fears of those who were concerned about Trump's racial attitudes.

Indeed, Trump’s candidacy triggered more worry and commentary about his racial attitudes than any significant presidential aspirant since segregationist Alabama Governor George Wallace won five southern states in the 1968 general election. President Trump’s early executive orders accelerating construction of a wall at the Mexican border and blocking entry to the U.S. of many Muslims only appeared to confirm the worst fears of many who did not support him.

Nonetheless, as unlikely as it may appear to his critics, President Trump is uniquely positioned to lead an epochal transformation—by bridging the historic political and economic divide between African Americans and other minority groups and his core working-class, rural white supporters. In doing so, he could become the engineer of one of the most important turning points in American race relations and reopen for the first time in a generation the possibility of more significant levels of African American political support for Republicans.

American presidents historically have had limited power over the policies that affected race and discrimination, and rarely did they use their direct influence in ways that were helpful to African Americans. For nearly 200 years, our presidents overwhelmingly made domestic stability for the majority white population a far higher priority than ensuring civil rights or equal opportunity for nonwhites.

First Year Video: Presidential Problems: Race And The Crisis of Justice

But presidents also have a long history of employing moral persuasion when they had no formal power over crucial issues—especially in times of crisis. Even before his inauguration, Trump himself expressed a willingness to use the soft powers of a president-elect to pressure American companies to keep jobs and factories in the U.S. And in modern times, presidents have been able to dramatically—and in some cases very swiftly—help the American population constructively reimagine and reshape deeply entrenched attitudes in areas such as the rights of women, minorities, gays, and others.

To fulfill the desire he expressed on election night to be “president for all Americans,” Trump must make a national address early in his first year using his trademark “no-nonsense” style to establish four critically important symbolic messages:

If President Trump can convince even a modest percentage of Americans of color that he can be a president for all people, he can open the door for a new policy agenda.

If President Trump can persuade even a modest percentage of Americans of color that he is acting in good faith on issues of race, he would open the door for a new policy agenda around which lower-income citizens of all races could rally, while simultaneously retaining support among other conservatives. Those policies should include the following:

Were President Trump to do nothing—or very little—related to racial disparity in the U.S., or acted only by using force to shut down participants in civil disturbances like those that occurred in Ferguson, Missouri, and so many other cities in recent years, his record would fit easily into a long pattern of presidential ineffectiveness on issues of race

Known as the father of the Bill of Rights, George Mason noted that slavery was a "slow poison...daily contaminating the minds and moral of our people."

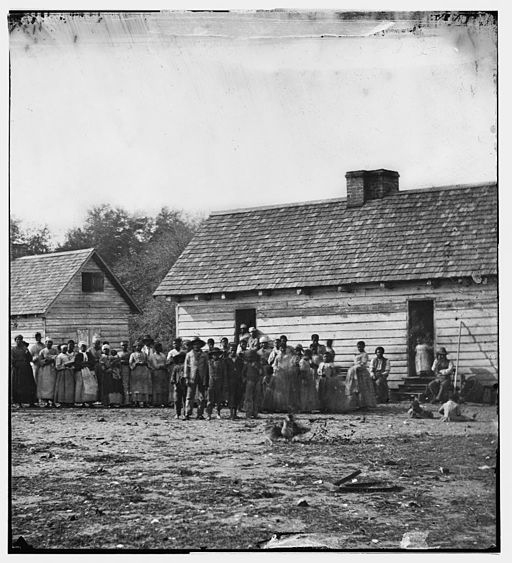

Slavery and the extended racial divisions it spawned are a vein of cruelty and immorality inextricably embedded in the bedrock of American history. George Mason—one of the principal architects of the American ideals defined in the Bill of Rights—correctly identified slavery as a “slow poison . . . daily contaminating the minds and morals of our people.” The challenge posed to presidents by that poisoned history has evolved profoundly through three great eras. First, there was chattel slavery from Mason’s colonial period to the Civil War; then the century of legally mandated segregation that followed; and, most briefly, the modern era in which the civil rights of all races are acknowledged in the law but ongoing discrimination and vestiges of past conduct still deform U.S. society.

There were, of course, certain presidents remembered heroically for bold action on race: Abraham Lincoln most of all, for declaring an end to antebellum slavery and holding the nation together through the Civil War; Franklin Delano Roosevelt for opening federal jobs to African Americans in the 1940s; John F. Kennedy for endorsing legislation to end Jim Crow segregation in 1963; and Lyndon Johnson for fulfilling Kennedy’s vision and then extending to African Americans rights and assistance far greater than JFK could have imagined.

But over most of American history, it was astonishingly rare for presidents to take any action related to race, in the first years of their terms or any other. When presidents did act, it was overwhelmingly bad for African Americans or other minorities.

This is for a simple reason: One-third of American presidents served during the era of antebellum slavery, during which time eight chief executives personally owned slaves, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and Andrew Jackson. Overwhelming evidence today suggests that Jefferson fathered multiple children with an enslaved woman on his Virginia plantation, and it would be unsurprising if that were not the case with other founding fathers, given how common such coerced liaisons were in the period of slavery.

The early U.S. presidents viewed the debate over slavery as a threat to the unity and stability of the nation.

While Jefferson and others at times expressed reservations about the morality of slavery, the early presidents all accepted that their only legitimate role in relation to race was extraordinarily narrow. From the beginnings of the American republic to the end of the 1850s, there were no “issues” related to race beyond the fundamental question of whether the practice of slavery would expand into new territories or be abolished from all U.S. territory. Furthermore, almost every president viewed slavery less as a question of morality or a test of American principles, but primarily focused on whether the debate over slavery threatened the unity and future stability of the still-young nation.

As a result, as historian Russell Riley at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center has written, even presidents who had personal doubts about the morality of slavery repeatedly took positions against abolitionist agitators, in the belief that their primary responsibility as chief executive was to preserve the Union, rather than extend freedom or justice to the enslaved.

For most of a century, when action related to race did come from a U.S. president, it almost invariably gravitated toward actions that would defeat any efforts to end slavery or moderate its most terrible dimensions. As the conflict that would ultimately trigger the Civil War in 1861 grew more sharp, presidents were more often compelled to act.

In modern times, there is no serious debate about the immorality of slavery. But in the context of the decades leading to the Civil War, presidential actions related to race were almost always predicated on a reversal of that basic morality as it would be understood 150 years later. Loyalty to the republic and a commitment to preserving the Union were—just as they are today—a foundation of American civic values. Since slavery was critical to a national economy hugely reliant on agriculture—and cotton production in particular—then challenges to slavery were also challenges to the preservation of the entire nation. By that harsh logic, a patriot was compelled to accept the institution of slavery as an ethical necessity to protect the United States itself.

The result was that all presidential actions related to slavery in the decades prior to the Civil War were shaped by a grand bargain in which the destruction of the lives and happiness of millions of enslaved men, women, and children were seen as an acceptable price for sustaining the new American republic and its extraordinary opportunities for the descendants of European colonists.

In 1837 President Martin Van Buren used his inaugural address to endorse a policy adopted by his predecessor, Andrew Jackson, that banned antislavery literature from delivery through the U.S. postal service and attempted to suppress much other abolitionist activity. In response to talk of a congressional measure limiting slavery in the District of Columbia, Van Buren swore to veto any such provision. He cautioned about tampering with “domestic institutions which, unwisely disturbed, might endanger the harmony of the whole . . . republic.” Those who sought to preserve slavery were, like the founding fathers, “humane, patriotic, expedient, honorable, and just,” Van Buren said, while those who pushed to limit or end slavery were the “wicked.”

That pattern continued until the nation reached the brink of civil war, as presidents repeatedly turned their backs on opportunities to reduce or eliminate the oppression of slavery in deference to regional leaders who insisted that forced labor and involuntary servitude must remain the economic foundation of the 19th-century United States and its expansion westward.

Yet even within this generally abominable record of presidential leadership on race, there are lessons President Trump could draw—in particular the power of moving boldly on principle and contrary to party expectations in the first months of a presidency.

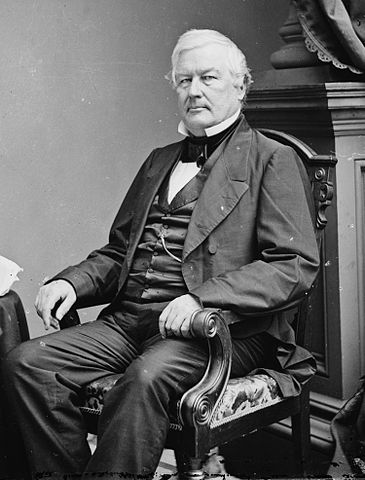

In 1850, the question of whether new territories such as California and New Mexico would be admitted into the Union as free states or slave states immediately confronted newly inaugurated President Millard Fillmore. His ascension from the office of vice president came with the sudden death of his predecessor, Zachary Taylor—the last president to have been a slave owner.

President Millard Fillmore went against expectations by supporting the Compromise of 1850.

Over the course of his political career, Fillmore, a New Yorker, had been a friend of abolitionists and was viewed as generally opposed to slavery. Once in office, Fillmore was faced with whether to support an agreement proposed by Taylor before his death to allow the new territories to join the country as “free” states and at the same time guarantee the uninterrupted preservation of slavery in the states where it already existed. In a historic turn of fate, Fillmore during his first year in office went against public expectations and his previous positions to instead support the sweeping Compromise of 1850. That agreement simultaneously pulled the country back from the verge of disunion and enlarged the free territories of the nation. But at the same time, it also imposed even more draconian limits designed to prevent interference with slavery in the South. Through the infamous Fugitive Slave Act, the agreement also blocked all efforts to liberate any of the several million African Americans already shackled to the yoke of involuntary servitude.

Over time, the cruelties of the proslavery aspects of the compromise inflamed antislavery factions even further, but Fillmore’s political reverse at the start of his administration demonstrated the effectiveness of a first-year presidential blitzkrieg—even when the president was acting on entirely wrong convictions.

In the century after the Civil War, U.S. presidents, with some exceptions, continued a pattern of failure to preserve the hard-won rights of former slaves. A cynical agreement to settle the disputed presidential election of 1876 awarded the White House to Republican Rutherford B. Hayes, in return for ending Reconstruction in the South and the removal of Union troops. Hayes’ first year began decades of the federal government turning a blind eye as whites in the former Confederate states proceeded with the systematic reassertion of their political and economic subjugation of African Americans.

This failure of national will and presidential leadership ushered in another 80 years of excruciating dispossession, in which huge numbers of African Americans remained in a state of “neoslavery,” and forced labor became as central to the resurrection of the U.S. cotton economy as antebellum slavery had been a generation earlier.

President Woodrow Wilson allowed Jim Crow segregation practices to be adopted in the federal government, reducing the number of African Americans appointed to federal jobs.

In the first years of the 20th century, President Woodrow Wilson allowed Jim Crow segregation practices to be adopted in the federal government, dramatically reduced the number of African American appointees to federal offices, and did virtually nothing to blunt a wave of lynchings and civil terror that followed the efforts of black military men to vote or assert economic independence after returning home from World War I. Nearly two decades before his election in 1912, Wilson had written that the resubjugation of blacks after the Civil War was “the natural, inevitable ascendancy of the whites.” Wilson never retreated from such views.

The Democratic Party already was openly the party of white supremacy, but the Republican Party—which had once proudly claimed its mantle as “the party of Lincoln and of emancipation”—also was turning its back on African Americans. In his inaugural address in 1909, Republican President William H. Taft applauded how whites in the South had successfully engineered new voting restrictions to prevent almost all blacks from voting—thwarting the “danger of . . . an ignorant electorate.”

After World War II, newly invented farm equipment began to eliminate the need for black laborers in the farm fields of the South.

In the 1930s, before FDR opened federal jobs to African Americans, he brokered passage of his New Deal programs partly with promises to racist southern U.S. senators that the programs would never challenge segregation. After the World War II era—as newly invented equipment and chemicals began to eliminate the need for millions of black laborers in the farm fields of the South—the continued oppression of African Americans slowly became less necessary to the preservation of the Union. That allowed for the first time since the Emancipation Proclamation the possibility of presidential actions that might meaningfully benefit black citizens.

In the early 1960s, President Kennedy ordered federal troops to Mississippi to enforce the court-ordered desegregation of a state university. Moved by terrible violence being unleashed on civil rights workers in the South in 1963, he gave a national address promising a new law to end racial segregation and guarantee the economic and political rights of African Americans.

Before its passage, however, Kennedy was assassinated. His successor, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, once again demonstrated the power of moving swiftly and against expectations. In stark contrast to his past profile as a vulgar Texan from a state with a long history of extreme racial oppression, Johnson demanded swift action on Kennedy’s civil rights bill, and forged an unorthodox coalition of northern Democrats and moderate Republicans to pass it. Despite his recognition that enactment of the law would likely sever from his party “the South for a generation," as he reportedly told an aide, Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law on June 19, 1964—the signature achievement of his first year in office.

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, which was a signature achievement of his presidency and one of the most important laws in U.S. history.

By moving quickly, in the earliest days of his presidency, and leveraging the grief of American voters, Johnson achieved a legislative victory long thought impossible, and one with vast tangible benefits for African Americans. The Civil Rights Act would become one of the most impactful laws in U.S. history.

Kennedy and Johnson also dealt with a president’s limited powers to affect race by using the prestige and moral authority of the White House to engage in day-to-day developments related to the civil rights movement, or to coerce and cajole local officials into reforming their own behavior. Both men directly called southern governors and other local officials to demand protection for civil rights activists.

In August 1965, for example, Johnson instructed aides to become involved when local funeral homes in Alabama refused to transport the body of slain civil rights activist Jonathan Daniels, a young priest from New Hampshire who had been gunned down by an Alabama deputy sheriff.

In total, only seven presidents, beginning with Richard Nixon, have held the White House since the final dismantling of legally mandated segregation. Among those, the first three—Nixon, Jimmy Carter, and Ronald Reagan—governed in an era in which discussions of race were dominated by debate over legislation directly derived from the civil rights movement and its constitutional reinterpretations: funding for private schools, the question of whether federal powers allowed intervention in segregated neighborhoods, whether Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. should be honored with a national holiday.

Since the administration of George H. W. Bush beginning in 1988, however, presidents have faced an increasingly elusive challenge in guiding the nation on race. Opposing overtly discriminatory laws, or combating self-proclaimed hate groups, has been replaced by debates over measuring economic progress, the sources of social ills, and most explosively, interaction between the police and African American citizens. Meanwhile, Supreme Court rulings have undercut the once-certain symbolic reauthorizations of key federal civil and voting rights statutes.

Despite a generally more tolerant atmosphere toward race, presidents continued to be reticent about embarking on dramatic initiatives early in their terms. One result was that more often presidential engagement would come, as so often in history, only at the height of civil crisis.

In 1992, riots broke out in Los Angeles, California, after a video emerged that showed four Los Angeles police officers beating motorist Rodney King.

In 1992, George H. W. Bush was the first modern president to confront the power of citizens and the media recording what appeared to be police misconduct toward a citizen, when grainy video of four Los Angeles police officers beating motorist Rodney King triggered days of massive riots. Bush condemned the actions of police and urged calm on the part of citizens, but he was unable to stem a tide of violence that spread to Atlanta and other cities.

His successor, President Bill Clinton, struggled to address outrage over New York police mistreatment of Haitian immigrant Abner Louima. Clinton’s national “Advisory Panel on Race” was widely viewed as remote and ineffective. George W. Bush attempted to shift discussion around the struggles of minorities away from a focus on past discrimination and toward expanded opportunity and improved public schools. But his signature No Child Left Behind education initiative came to be seen as widely ineffective, especially for poor and minority children.

President Barack Obama, as the first African American to occupy the White House, entered office with an explicit promise to heal the divisions within U.S. society. Yet his tenure was characterized by a spike in racial tensions and multiple episodes of questionable police conduct followed by civil disturbances. As his administration came to an end, it was unclear what, if anything, would become of recommendations from a special presidential commission on police practices that he convened.

Both Clinton and Obama—arguably the two modern presidents most popular among African Americans—were applauded for resonant, sweeping oratory around race, but each struggled to find genuine traction and effect after key events that galvanized the public. Their calls for a “national dialogue on race” never moved beyond rhetoric. “It sounded good, but it just didn’t do much,” said former Mississippi Governor William Winter, who cochaired the national commission organized by President Clinton. Both the Clinton and Obama presidencies ultimately left many black citizens with a deep sense of unfulfilled promise.

On first examination, Trump would seem highly unlikely to have any greater success in restoring racial civility. While announcing his candidacy in June 2015, he infamously declared that undocumented Mexican immigrants were “bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”

After civil unrest erupted in Ferguson and Baltimore in response the deaths of young black men during confrontations with local police, Trump criticized protestors and rioters and rebuked the emerging Black Lives Matter movement. “I think they’re looking for trouble,” he said on Fox News.

He repeatedly emphasized support for police officers, skepticism toward the victims of police violence, and comfort with tactics such as “stop-and-frisk,” a police search strategy primarily aimed at black citizens that has been declared unconstitutional by a U.S. judge.

After Georgia Representative John Lewis criticized Donald Trump, the president lashed out at him.

During the presidential campaign, Trump repeatedly—and incorrectly—asserted that areas with predominantly African American populations were engulfed in crime, drugs, and poverty. After Georgia Representative John Lewis, an iconic figure from the civil rights era, criticized Trump shortly after his inauguration, the new president castigated Lewis and declared his home district to be “crime-infested” and “falling apart”—apparently unaware that the area contained some of Atlanta’s most prosperous commercial and residential neighborhoods.

Yet at the same time, Trump also insisted throughout the campaign that he was committed to the economic uplift of minorities—especially inner-city black families—and that he is “the least racist person there is.” He claimed that his racial views were distorted by critics and the media. In his victory speech after the surprise outcome of the election, Trump promised to be “president for all Americans.”

After five Dallas police officers were killed in a surprise attack in July 2016, Trump issued an uncharacteristically tempered statement: “Our nation has become too divided. Too many Americans feel like they’ve lost hope. Crime is harming too many citizens. Racial tensions have gotten worse, not better. This isn’t the American Dream we all want for our children. This is a time, perhaps more than ever, for strong leadership, love, and compassion. We will pull through these tragedies.”

As the first year of the Trump presidency gets underway, the nation’s new chief executive has the chance to learn from his predecessors by setting a new and unexpected civil rights agenda, and moving quickly and confidently to help his followers see the shared interests of all who have been “left behind” by the U.S. economy, regardless of race. It could be his most historic achievement.