“Who would want to read a book on disasters?”

That was the question John F. Kennedy put to an aide in late 1961 upon hearing that journalists were thinking about writing books on the first year of his presidency. It was a loaded question, as Kennedy was quite familiar with the book market, having written two popular volumes of history, including one on a political and military disaster. And there was no denying that his previous 12 months had been filled with foreign policy missteps—the most notable being the failed invasion at Cuba’s Bay of Pigs.

But, as Kennedy himself might have imagined, any book on that difficult year would have included his response to those “disasters” and thus made it an attractive read, for it would have offered something of a primer on how to make a course correction early in one’s presidency. Among its lessons would have been the need to (1) surround oneself with loyal and trusted advisors; (2) consider the wisdom of the outgoing administration; (3) insist on a full and frank discussion of contingencies; (4) maintain multiple channels of communication with adversaries; and (5) allow your adversary a dignified retreat. These lessons were hard-earned, and not without qualification, but they flowed directly from decisions Kennedy made during his first months in office, and especially in the wake of the Bay of Pigs fiasco that April. While Kennedy’s first year is about much more than the Cuban misadventure, that epic failure loomed large and would condition national security policy for the remainder of his presidency.

*

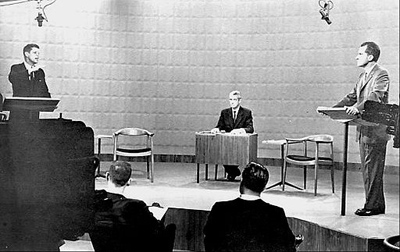

Cuba, in fact, figured prominently in Kennedy even gaining the presidency. Throughout the presidential contest of 1960, the Democratic senator challenged Richard M. Nixon, the sitting vice president, on the Republicans’ handling of Cuba policy. It was on the GOP’s watch, Kennedy charged, that Fidel Castro had engineered his revolution and cozied up to the Soviet Union. Kennedy called for measures to forestall Castro’s full consolidation of power and absorption into Moscow’s orbit, criticizing President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and by extension Nixon, for insufficient vigor in meeting the communist threat. Privately Nixon fumed, knowing he had to stay mum about the ongoing training of Cuban refugees who were to take part in a CIA plan for anti-Castro military action. While Kennedy muted his attack during the later stages of the campaign, his earlier charges hit home and likely contributed to electoral victory that November.

During the presidential debates in 1960, Kennedy criticized Nixon and the Republicans for their handling of Cuba.

Kennedy refrained from public comment on Cuba during the presidential transition as he shifted his efforts from running to governing. But the narrow margin of his popular victory and the hawkish tenor of his campaign rhetoric narrowed his room for maneuver once he took office. Having laid the groundwork for a more assertive posture in the Cold War and specifically toward the Castro regime, Kennedy heightened the consequences of inaction were he not to make good on his pledge of greater activism. The domestic politics of foreign policymaking, particularly for a Democratic Party still smarting from partisan battles over the Chinese communist revolution and the impact of McCarthyism, thus constrained Kennedy’s policy options and sustained the momentum toward anti-Castro military action.

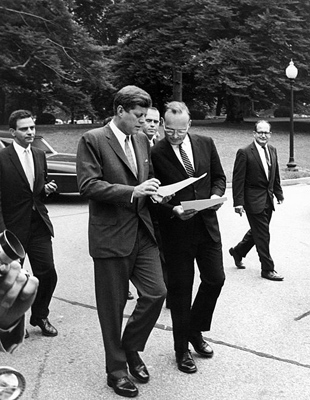

The choices Kennedy made during this period on personnel, process, and priorities also conditioned his approach to Cuba and shaped the contours of his national security policy making more broadly. These included the particulars of agenda setting, which took place in conjunction with a series of preinaugural task forces on a wide range of domestic, defense, and foreign policy topics. Cuba was on his mind throughout this period, but it hardly dominated the conversation internally or with President Eisenhower during their transition meetings, sharing space with Berlin, the developing world, the Far East, the nuclear threat, and foreign aid.

President Eisenhower greets President-elect Kennedy on December 6, 1960. The two men discussed a range of foreign affairs including Cuba, Berlin, the nuclear threat, and foreign aid.

Nowhere in this mix, however, was there any indication of which subjects Kennedy would tackle first as president, how he might sequence his agenda thereafter, or how he understood the threats that each challenge posed. Indeed, his national security advisor, McGeorge Bundy, acknowledged that the incoming administration would simply respond to external events as they arose, and that high-level planning would focus primarily on capabilities and tactics. Overarching statements of strategy were likely to be so broad as to be useless, and if divorced from the budgetary process, would fail to meet the strategic imperative of matching means with ends. In any event, Bundy recognized, administration positions would become apparent through the issuance of statements on presidential and departmental policies.

Accordingly, Kennedy showed no interest in establishing a comprehensive and coherent national security strategy for his administration. He chose neither to review Eisenhower’s basic national security policy during the transition nor to consider how the many threats facing the United States fit into a broader conceptual approach to national security. In fact, he never settled on a formal, articulated statement of security strategy for the entirety of his presidency. Although aides began the process of fleshing one out in 1961, it never received Kennedy’s final sanction, not the least of reasons being the president’s discomfort with such documents and their potential for limiting his range of options.

As President Kennedy’s National Security Advisor, McGeorge Bundy, focused on external events as necessary rather than on formulating strategy statements.

If there was a strategic lodestar for the administration, it was the principle of “flexible response.” Having emerged in reaction to Ike’s perceived reliance on nuclear weapons for addressing all manner of enemy hostilities, Kennedy sought to calibrate American responses to communist provocations. A symmetrical approach to national security thus offered a range of choices, graduating in intensity, from the sublimited warfare of counterinsurgency, to the conventional warfare of battlefield maneuver, to, quite literally, the nuclear option itself. Following a review of defense policy early in his new administration, Kennedy beefed up military capabilities in each of these areas. While the ensuing fiscal expansion threatened to undo the ties that Eisenhower stressed between balanced budgets and national security, Kennedy regarded such deficit spending as a stimulus package that would allow him to grow the arsenal while growing the economy.

To enact his defense programs, as well as his foreign and domestic initiatives, Kennedy assembled a “ministry of talent” to populate a bipartisan cabinet and White House staff. The group was comprised of action-oriented, pragmatic policymakers—men made of stern stuff and smart as hell. “You can’t beat brains,” he’d quip about Bundy; it was a comment equally befitting Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Preferring to act as his own secretary of state, though, Kennedy settled on the taciturn Dean Rusk to lead Foggy Bottom. Kennedy also revamped the machinery of national security, molding it to his operational style to allow for a more fluid policy-making environment. Facets of the National Security Council that Eisenhower relied on to produce thoroughly vetted—and, to Kennedy, utterly stale—policy options and ventures were dismantled in favor of a leaner bureaucracy marked by a series of task forces on regional and functional issues.

Kennedy assembled a “ministry of talent” to populate a bipartisan Cabinet, shown here in at the Swearing-In Ceremony on January 21, 1961.

As a result, the locus of energy in the administration, at least for that first year, remained at the tactical level, as Kennedy and his advisors developed bilateral and regional policies without systematically assessing their relative importance or their strategic coherence. Initiatives and agencies such as the Peace Corps, the Alliance for Progress, and the Agency for International Development, for example, remained in tension with the Cold War impulses suffusing them, as the search for international stability often trumped efforts toward meaningful and lasting reform. While these and the aforementioned measures Kennedy adopted offered compelling rationales in isolation, all of them contributed to the “disasters” that were soon to come.

*

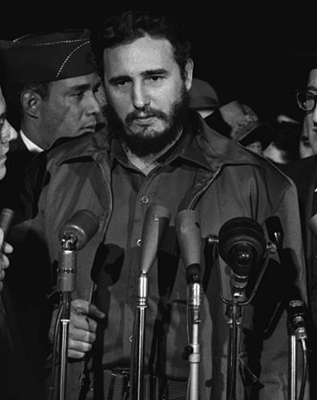

None were as traumatic or as consequential as the Bay of Pigs. While Kennedy’s first year included several low points—a testy exchange with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev in Vienna, a heightened sense of crisis over Berlin, the building of a wall separating that city’s eastern and western residents, and a showdown with Soviet tanks at Berlin’s Checkpoint Charlie—all paled beside the failed invasion of Cuba’s southern shore. Kennedy inherited a scheme to topple Fidel Castro from President Eisenhower, and though leery of involving himself in actions held over from the previous administration, he nevertheless sanctioned ongoing planning for the assault. Success of the plan was hardly assured, but fearing its design rendered the operation too “noisy” and thus too easily traceable to American sponsorship, Kennedy altered key elements of the proposed invasion, including the site of its landing and the scope of its air cover. It would prove a fateful move.

The Bay of Pigs, the failed invasion of Cuba’s southern shore, was designed to topple Fidel Castro who came to power in 1959.

Compounding his troubles, Kennedy’s national security team failed to conduct a meticulous evaluation of the revised plan and its chances for success, dooming the operation, now known as Zapata, to failure. Key principals never met with the president en masse to probe with sufficient rigor the veracity of guiding assumptions, the soundness of tactics, and the likely attainment of objectives; senior defense officials never fully dissected the particulars of what had come to be a military operation run by the CIA; and Kennedy himself failed to grasp the mantle of the entire process and demand both full candor and a full evaluation. Nor did the president gauge the impact of the operation on his goal of better hemispheric relations and his support of postcolonial nations worldwide. The result was indeed a disaster. Not only did the operation fail miserably, with over 100 members of the invasion force killed and roughly 1,200 captured, it came to be seen as an American project nonetheless—the very circumstance the president most sought to avoid. For Kennedy, the experience was shattering.

While the president accepted blame publicly for the humiliation, privately he seethed at the malfeasance, incompetence, or mendacity of key members of his national security team. He found himself equally culpable, wondering how he could have been so “stupid.” But failure at the Bay of Pigs wasn’t just the result of poor advice or bad judgment. It also stemmed from deficiencies within the machinery for national security policymaking, as the compartmentalized task force arrangement failed to provide an adequate means of fully vetting the operation. Eisenhower’s hierarchical NSC was not the right fit for the less-stratified Kennedy White House, but its emphasis on formal and systematic procedures might well have imposed the necessary rigor on the New Frontiersmen’s deliberative process. Kennedy’s own frenetic pace and style likely contributed to the disarray as well; in the aftermath of the crisis, Bundy complained to the president about how hard it had been to pin him down on specific matters and have him digest information in an orderly fashion. But failure in Cuba had a thousand fathers, for it occurred at every stage of the process—managerial, operational, and analytic—with too little forethought, too much improvisation, and too few profiles in courage.

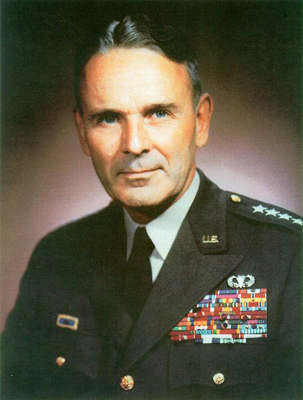

To conduct the operation’s postmortem, Kennedy turned to retired general Maxwell D. Taylor, whose earlier writings had popularized the term “flexible response.” Structural and personnel changes, even architectural ones, were soon in the offing. Bundy moved physically closer to the president, trading space in the Executive Office Building for a basement office in the White House. A new Situation Room would adjoin Bundy’s office, ensuring that classified information from the relevant national security agencies flowed uninterrupted to the national security advisor and his staff. Kennedy also reshaped his team, releasing or reassigning officials he deemed insufficiently loyal, supportive, or astute; these included top-tier policymakers at the State Department and the CIA. In time, Kennedy also replaced the Army and Navy chiefs of staff, and removed the chairman of the Joint Chiefs.

President Kennedy asked retired general Maxwell D. Taylor to oversee a postmortem after the failed Bay of Pigs invasion.

But merely swapping out one set of officials for another neither enhanced the quality of advice nor the frankness of those giving it. Kennedy therefore turned to men whose judgment he could trust and who could speak to him in utmost confidence. His increasing reliance on Special Counsel Ted Sorensen and even more so on his brother Robert, the attorney general, brought new voices into discussions of national security. Alongside Maxwell Taylor, who now served Kennedy as his military representative and mediated between the president and the Joint Chiefs, Bobby became a catalyst for the newly created Special Group coordinating counterinsurgency activities. The president thus shrewdly placed those closest to him in positions where they could lobby increasingly hard for the more activist elements of administration policy, and arguably those he deemed most important.

*

These changes and others conditioned Kennedy’s handling of national security for the remainder of his presidency. More formalized procedures for managing policy arose after the Bay of Pigs. In addition to the Special Group and its offshoots, an NSC standing committee assumed coordination of interdepartmental activities, stepping in to provide leadership where the State Department had proved wanting. Improvisation remained, however, and episodically to the good, as an executive committee of the NSC labored to resolve the Cuban Missile Crisis and other matters into 1963. In terms of personnel, Kennedy’s vow never to rely on the “experts” left him wary of recommendations coming from military and intelligence officials, stiffening his reluctance to intervene in Laos, his resistance to an American combat role in Vietnam, and his rejection of lethal force in resolving the Cuban Missile Crisis. Likewise, Kennedy resolved the Berlin tank crisis in October through his use of brother Robert and a secret back channel, and with an awareness of the need for U.S. as well as Soviet leaders to avoid escalation and humiliation; it was a lesson Kennedy would heed 12 months later when faced with Soviet missiles in Cuba. In addition, Kennedy’s willingness to establish a personal relationship with Khrushchev through a “pen pal” correspondence in late 1961, during a period flush with bellicose rhetoric and dramatic confrontation, may also have aided in the peaceful resolution of the missile crisis.

President Kennedy increasingly relied on his brother, Robert (right), to help him navigate foreign affairs.

But these lessons were offset by less salutary measures Kennedy took both prior to and following his early Caribbean misadventure. With public statements first rejecting the idea of a “missile gap” in Moscow’s favor and then acknowledging Washington’s superiority in nuclear weapons, administration officials openly needled Khrushchev and laid bare the reality of the strategic balance. Their continued agitation for Castro’s ouster further threatened Soviet interests, particularly at a time when Moscow was competing with Beijing for leadership of the communist camp. No one was more hawkish on Castro than Robert Kennedy, whose value to JFK in the wake of Zapata should not mask his contribution to the frictions that culminated in the placement of Soviet missiles in Cuba.

Kennedy’s approach also indicates that his sensitivity to rifts within the Communist world failed to shape policy in ways that moderated the belligerence of great power adversaries. While his détente with Moscow and isolation of Beijing contributed to the desired hardening of the Sino-Soviet split, the near-term benefits of the rift to Washington likely shrank with JFK’s escalation of the conflict in Vietnam. The influx of American military aid to Saigon helped to galvanize increasing Chinese and, eventually, Soviet support for Hanoi, as the two communist powers competed for influence and prestige in Southeast Asia and in the socialist world at large. While the rift and the war would intensify according to their own historical logics, Kennedy’s commitment to South Vietnam raised the stakes in the struggle, for East as well as for West, making peace and disengagement that much more elusive.

*

President Kennedy’s increased commitment to South Vietnam galvanized Chinese and Soviet support for North Vietnam.

In the wake of the missile crisis, the very ethos of crisis seemed to permeate national security decision making. McNamara’s apocryphal comment that there was “no longer any such thing as strategy, only crisis management,” captures the sense that events were outpacing the relevance of broader conceptual planning. The administration, however, had never tried to articulate a comprehensive and systematic strategy, and arguably had been engaged in crisis management since its first days in office. It may be that all presidential administrations are fated to do likewise as they respond to threats and opportunities both seen and unforeseen. But a failure to undertake a more comprehensive strategic review denied Kennedy the opportunity to establish priorities, to evaluate the coherence of proposed initiatives, and to consider more rigorously the implications of various policy options.

President Kennedy and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara worked within a national security team that was engaged in crisis management from its first days in office.

Instead, what the administration emphasized, and what gave its actions coherence, was the posture of flexible response. Yet flexible response provided no clear road map for articulating and prioritizing objectives, no ready framework for aligning ends with means, and no standard for evaluating or reconsidering threats. What it did offer was a rationale for the administration’s intrinsic urge toward activism, justifying both the expansion of means for countering threats—across the full spectrum of military capabilities—as well as the number and range of threats to be countered. A telling result of this logic was a sharply increased commitment of U.S. military advisors to Vietnam, which became a laboratory for the newly fashionable warfare of counterinsurgency. Kennedy deepened that commitment in late 1961, looking to prevent yet another “disaster” from taking place on his watch. The greater disaster, of course, was still to come.