“I used to think if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the Pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.” – James Carville

To the new president:

Eight of your predecessors confronted a major domestic financial crisis in the first year of their administrations—a sobering reminder that you can either harness the power of the nation’s economy, or be run over by it.

To succeed in the realm of fiscal policy and manage through an economic crisis, you must master four principal levers:

Each crisis that challenged your forebears was unique. So the good news is, you are unlikely to have to relive any of these particular nightmares.

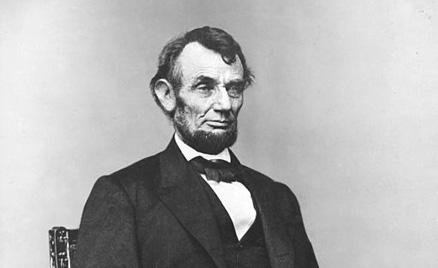

As the Civil War began, President Abraham Lincoln strained the economy to finance the military buildup, which lead to the Panic of 1861.

John Adams, Panic of 1797

Unbeknownst to Adams, a week before his inauguration, the Bank of England suspended payments in gold, which triggered a severe credit contraction in Britain and the U.S. The contraction burst a bubble of speculation in land and bankrupted merchants and speculators. Adams took no specific action about the Panic of 1797, probably because there was scant precedent for a national government to rescue banks, relieve the unemployed, and stimulate economic growth. The mid-term elections of 1798 produced growing tensions between nascent political parties. Adams’ strategy was to steer a middle course between the parties, which doomed his chance for re-election in 1800.

Martin Van Buren, Panic of 1837

Within weeks after Van Buren’s inauguration, a bank panic broke out in New York and other eastern cities. This had its roots in rising interest rates in Britain, the falling price of cotton, and policies of Van Buren’s predecessor, Andrew Jackson. In May, 1837, Van Buren called for a special session of Congress, to convene in September. His proposal was to reorganize the U.S. Treasury to hold gold reserves in federal sub-treasuries, rather than banks, around the country. Congress balked until 1840, when it approved the bill. Popular anger over the panic and subsequent depression echoed in the mid-term elections of 1838, which enlarged seats of the opposition party in Congress. Van Buren lost his bid for re-election in 1840.

James Buchanan, Panic of 1857

Rising interest rates in England and the U.S. pierced a speculative bubble in land and shares of stock in new railroads. The collapse from August to October 1857 of institutions that had financed the speculations triggered bank runs and suspensions across the nation. The economic contraction sparked riots for bread and strikes by workers. Government tax revenues plunged. Buchanan’s specific response to the crisis was to hold the states responsible for relief to unemployed workers; he said that the federal government was “without power to extend relief.” The panic aggravated debates over tariffs, homesteading, and slavery, and generally contributed to the widening gulf between the North and South. The mid-term elections saw major losses for Buchanan’s party. Buchanan retired from public life in 1861.

Abraham Lincoln, Panic of 1861

With the onset of the Civil War, Lincoln and his Treasury Secretary, Salmon P. Chase, strained to finance the military buildup. Congress approved new taxes and authority to issue bonds. In December 1861, the Treasury sold $150 million in bonds to banks, which were required to pay for the bonds in specie (gold and silver). This massive drain of specie, plus public disbelief in the stability of the banking system, prompted panic. The banks responded by suspending specie payments. The Treasury followed suit by suspending specie payments on its notes. In February 1862, Lincoln signed the Legal Tender Act, which would sustain specie suspension by the federal government for two decades and launched the “greenback era” of fiat money. The Democrats made significant gains in the elections of 1862, attributable not only to the banking crisis but also to emancipation, suspension of habeas corpus, and endorsement of a militia draft. In February 1863, Lincoln endorsed the National Banking Act, which reformed the financial system and introduced federal regulation of nationally-chartered banks.

Grover Cleveland, Panic of 1893

A few days before Cleveland’s inauguration, a major railroad failed. This was followed within weeks by the bankruptcy of a large industrial trust. And on April 21, the gold reserves of the U.S. government fell below the prudent minimum, prompting a stock market crash. Runs on banks began as depositors feared the collapse of the government and the financial system. At the core of this crisis was the Sherman Silver Act of 1890, the unintended consequence of which was an arbitrage against the gold reserves of the U.S. Treasury, which canny traders exploited shortly after enactment. Cleveland summoned Congress into an emergency session in August, aiming to repeal the provisions that created the arbitrage; Congress ultimately relented on November 1. Depletion of the Treasury’s gold reserves continued through the balance of 1893 and 1894 owing to outstanding legal tender gold notes that had to be honored. In early 1895, Cleveland retained J.P. Morgan to issue bonds in Europe for the purchase of gold, under the authority of a little-known law passed during the Civil War. Morgan’s syndicate successfully issued the bonds, the government purchased gold and shipped it to the U.S., and confidence in the financial system returned. But the panic and subsequent recession split Cleveland’s party and crushed his support in the following mid-term and presidential elections.

Herbert Hoover, Crash of 1929 and Panics of 1930 and 1931

Almost eight months after Hoover’s inauguration, the stock market began a spectacular crash and would ultimately plummet 85% in value. The Great Depression produced mass unemployment, widespread bankruptcies, and bank closings. Caught between progressives who insisted on government relief programs and conservatives who insisted on not responding, Hoover convened a high-level conference of business and government leaders in which he sought to gain voluntary commitments to maintain prices, wages, and unemployment. These commitments unraveled as the depression deepened. Hoover signed the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff in 1930, in the belief that high tariffs would help to boost domestic production. He declined proposals to undertake a massive public works program or to support relief for the unemployed. This, combined with his eviction of bonus marchers from Washington, D.C., fueled criticisms of indifference to social distress. Eventually, he agreed to sign legislation to establish the Reconstruction Finance Corporation that would invest government funds in ailing firms. And in February 1932, he endorsed legislation to modify the supposedly inviolable gold standard and allow the Fed to discount a wider range of securities. In July 1932, Hoover signed the Federal Home Loan Bank Act, establishing a system to provide liquidity and oversight to building and loan associations. Yet his presidential activism was too little, too late. The Republican House majority of 62% in 1928 fell to 28% of the seats after the election in November 1932.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Panic of 1933

A fresh wave of bank runs in the month before Roosevelt’s inauguration heralded renewed virulence of the Great Depression. FDR declined to embrace any of Hoover’s policy proposals before inauguration. In his first inaugural address, FDR set a tone of confidence, determination, and activism. Two days later, he issued a proclamation declaring a national bank holiday and calling Congress immediately into special session. What ensued was the famous “100 Days” in which Congress enacted some 15 pieces of major legislation, much of it a government safety net stitched from stimulus spending, jobs programs, deposit insurance, bank resolution, and new regulations on the financial sector. Roosevelt led the U.S. off the gold standard. Through the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, the government became an active financier of last resort not only to banks but also industrial firms. Yet, John Maynard Keynes criticized FDR for emphasizing reform over recovery. And historians today debate whether FDR’s response was so different from the direction in which Hoover had been heading in his final months. Roosevelt’s Congressional majority was sustained at the 1934 mid-term election. And FDR was re-elected to three more terms in office.

Barack Obama, Panic of 2008-9

This crisis climaxed in August through October, with the collapse and/or bailout of financial institutions, a stock market crash, and financial distress of industrial firms. Regulators of the financial system—mainly the Fed and FDIC—intervened to stabilize the financial system through radical new monetary tactics and the exercise of a little-used provision of the Federal Reserve Act. In 2008, President George W. Bush’s administration took various steps to quell the panic: stabilizing financial institutions and industrial firms, urging calm, and using existing powers in new and novel ways. But the flurry of interventions by the government triggered populist revulsion that took shape as the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street social protest movements. The elections in November 2008 returned large Democratic majorities to Congress and a Democrat to the White House. As in 1933, the new president declined to endorse the crisis response of his predecessor. Eight days after Obama’s inauguration on January 20, 2009, Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion economic stimulus plan. In 2010, Obama signed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act.

When Franklin Roosevelt took office during the Great Depression, he set a tone of confidence, determination, and activism.

Despite their heterogeneity, these cases yield several lessons for your serious consideration.

Almost one in five U.S. presidents confronted a major domestic financial crisis in the first year of his administration. And half of all presidents faced a major financial crisis at some point.

Barry Eichengreen, an economist at Berkeley, wrote, “A crisis is a time when the pace of events seems to accelerate and when information is especially incomplete.” A severe financial crisis damages not only the financial system (“Wall Street”), but also the real economy (“Main Street”), in the form of lost output, curtailed R&D and capital investment, rising unemployment and bankruptcies, and the appearance of bread lines and civil unrest. According to one estimate, the economic output lost to a banking crisis amounts to 23% of GDP, a massive setback.

A financial crisis can presage regime shift—a durable change in voting behavior. Populist anger toward elites is a regular response to major domestic financial crises, exemplified by the Tea Party and Occupy Wall Street after the Panic of 2008, William Jennings Bryan and the populists after the Panic of 1893, and the Whigs after the Panic of 1837. At the mid-term elections following the eight crises profiled here, the median decline in House seats held by the president’s party was 12%—twice the average loss of seats in the House in non-crisis mid-term elections. Cleveland suffered a stunning 35% decline in the House, which remains the record today. FDR, however, experienced a gain of 2% in the House and 11% in the Senate. Regime shift could move either way, depending on how the president handles the crisis.

Today, the phrase “financial crisis” is used loosely to embrace a wide range of events: stock market crashes, bank panics, sovereign bond defaults, market closings, illiquidity, institutional collapse, and sharp currency declines.

But not all of these are worth your intervention. What should command the president’s time and attention is an event that threatens the safety and soundness of the national financial system and the real economy. Such instability is unambiguous, costly, and longer in duration.

Populist anger toward elites, such as the Occupy Wall Street protest, is a regular response to major financial crises.

Most financial crises are localized and have little long-lasting impact. The decline and bankruptcy of Enron in the fall of 2001—in George W. Bush’s first year as president—potentially threatened the stability of financial and energy markets just one month after the 9/11 terror attacks. But Bush decided against any intervention. In 1998, a run on Long Term Capital Management, a hedge fund, threatened the stability of the financial system; the Fed, not President Bill Clinton, used its influence to organize an orderly liquidation of LTCM. President George H.W. Bush declined to intervene in the crash of the junk bond market following the indictment of Drexel Burnham Lambert in 1989. Various sharp but short stock market crashes in 1987 and 2010 elicited no presidential action. Thus, the staple response to smaller and more local events is for the president to do nothing and let the markets cure themselves, with appropriate regulatory oversight.

Various federal laws empower agencies such as the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Financial Stability Oversight Council to stabilize the financial system in a crisis. Their tools include auditing and investigating, imposing capitalization standards, managing interest rates, injecting liquidity and capital into the system, and implementing “circuit breakers” to suspend trading in financial markets that are spiraling out of control. All of these are time-honored responses but are not to be implemented lightly. The dilemmas will be less about whether to implement these tactics and more about when and how.

Though powerful, the regulators are limited in the scope of their discretion. The president complements the agencies with other vectors of response. One vector entails initiating reforms of the financial system to enhance stability and forestall another crisis. Van Buren, Lincoln, Cleveland, and Roosevelt led such efforts. In June 2009, the Obama administration advanced proposed regulatory reforms that ultimately emerged as the Dodd-Frank Act in 2010, the most significant change in financial sector regulation in 76 years.

A second vector is promoting transparency. During a crisis, decision makers and the public need to know what is going on. You can promote transparency through executive orders, wise legislation, and study commissions. Transparency helps to relieve problems caused by information asymmetry. The National Banking Act of 1863; the Federal Reserve Act that grew out of the Panic of 1907; FDR’s legislative agenda in 1933 and 1934; and the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 all imposed new public reporting requirements on financial institutions. Sunlight may be the “best disinfectant,” but transparency comes with a cost, such as time-consuming reporting and bureaucratic oversight.

A third vector is relieving distress and stimulating the economy. Repairing the real economy is the province of the president, for which you have the full panoply of instruments: fiscal stimulus spending, social relief, executive orders, government contracts, anti-trust and tax policy, and the “bully pulpit” for exhorting decision makers to action.

In response to the Panic of 2008, George Bush and Barack Obama deployed their administrations to nudge nearly $1.5 trillion in fiscal spending bills through Congress, stimulate the economy, bail out industrial firms such as General Motors and Chrysler, promote mergers of failing institutions, and assist distressed mortgage borrowers.

During the Great Recession, Presidents Bush and Obama used a variety of tools such as fiscal spending bills and bail outs to try to relieve distress and stimulate the economy.

It was not always thus. Adams, Van Buren, Buchanan, Lincoln, and Cleveland did nothing for relief and economic stimulus. The tide turned with Herbert Hoover. Today voters are likely to expect some presidential intervention to address the damage to the real economy from a major financial crisis.

Nobel Laureate in Economics Milton Friedman and his collaborator, economist Anna Schwartz, wrote: "The detailed story of every banking crisis [is that] … In the absence of vigorous intellectual leadership … the tendencies of drift and indecision had full scope. Moreover, as time went on, their force cumulated. Each failure to act made another such failure more likely."

Presidential leadership in a financial crisis is a matter of asserting priorities, mobilizing a coalition, and communicating well to decision makers and the public. You alone are not in control of crisis-fighting. But you have immense influence and convening power necessary to coordinate actions across the federal government. In addition to coordinating and motivating regulators, the president must work with Congress—often with the opposition party—on legislation involving fiscal stimulus and changes in financial regulation. Turning to Congress was among the earliest steps of Van Buren, Lincoln, Cleveland, Roosevelt, and Obama.

Engaging the opposition, however, is both expedient and fraught with danger, since the opposition will certainly sense the potential for regime shift. Generally, presidential legislation responding to a financial crisis has garnered scant support from the opposition. Offering a response to the crisis that is partisan and polarizing is especially risky: Van Buren, Buchanan, and Cleveland all did, and their parties suffered the consequences.

The potential for regime shift poses a stark choice: Master the crisis or be mastered.

President Obama’s first chief of staff, Rahm Emanuel stated, “you never want a serious crisis to go to waste.”

“You never want a serious crisis to go to waste. And what I mean by that is an opportunity to do things that you think you could not do before,” Rahm Emanuel, President Obama’s first Chief of Staff, said in 2008.

Lincoln, FDR, and Obama made broad changes in financial regulations. Reagan significantly restructured the Savings and Loan industry. FDR and Obama also harnessed their crisis momentum on behalf of social legislation.

A first-year first term financial crisis calls for pragmatism and agility. Despite the fact that Van Buren campaigned on a continuation of Andrew Jackson’s system of “pet bank” depositories for gold reserves, he swung his support to a sub-treasury system after the Panic of 1837. FDR’s platform in 1932 advocated a balanced budget, which he abandoned in 1934. He also campaigned against federal deposit insurance, but later endorsed such legislation. Teddy Roosevelt, the trust-buster, endorsed a major merger in the steel industry to help quell the Panic of 1907. In the face of a run on the dollar in 1971, Richard Nixon abandoned the gold standard, famously saying “I am now a Keynesian in economics.”

Turning from strong ideology or campaign promises is politically risky, though voters may forgive a pivot in the face of extreme circumstances.

Take action commensurate with the threat and with the context. Interventions risk making the financial system less nimble and more costly and can promote moral hazard. Government intervention in crises (large and small, systemic and local) may create an incentive for risk-taking, which can amplify and accelerate the next crisis.

Also, the impact of a financial crisis will vary considerably by industry, region, and socio-economic class. It is a mistake to assume that the impact is homogeneous across the nation and world. Industries such as health care; education services; and food, beverage, and tobacco products actually grew in 2009 and 2010; in contrast, oil and gas exploration and output in automobile and furniture manufacturing fell sharply. In 1857, the manufacturing North suffered much more than the plantation South.

The president must target remedies to the crisis in ways that deal most effectively with the threat and its impact.