The first year of the first Bush administration demonstrates that less can be more. More happened on the international stage during those first 12 months than for any other president in American history. A democratic tsunami overwhelmed European communism. The Berlin Wall fell. The Cold War effectively ended. Tiananmen Square transformed from a place to an event. Coups failed in Panama and the Philippines, the first due to American indifference and the second because of American action; the former setting the stage for the eventual invasion of Panama and arrest of Manuel Noriega, the latter for Corazon Aquino’s continued leadership of a vital U.S. ally. All this in a single year, and from Washington’s perspective, save for events in China, nearly all positive.

It didn’t have to work out that well. Profound changes carry incalculable dangers. Collapsing states frequently bring ethnic violence and retribution for historic affronts. Mass protests can lead to crackdowns, civil war, or coups, the condemnation of which brings diplomatic problems of their own. As Robert Gates frequently noted from his post as Bush’s assistant national security advisor, never before in history had a great power collapsed without an ensuing great power war. Never before, he need not have added, had nuclear weapons been involved. Peacefully navigating the potential rocky shoals of the Soviet Empire’s disintegration in particular therefore meant avoiding or at least tempering scenarios that historically brought devastating results.

During George H. W. Bush’s first year as president, the Berlin Wall in Germany was dismantled, and the Cold War effectively ended.

Officials of the George H. W. Bush administration navigated these shoals because they declined to act decisively at all when clear policy choices did not present themselves, providing a lesson that less can indeed be more. Theirs was a Hippocratic approach to diplomacy, predicated upon first doing no harm. More than President Obama’s recent dictum against doing “stupid shit,” and certainly more than laziness or bureaucratic inertia, this was instead a conscious choice to avoid anything that might hinder their overall successful trajectory. Convinced of the appeal of American ideas and the inherent power of the American economy and military, and more fundamentally convinced that world affairs generally trended in democracy’s direction, they strove above all to do nothing that might jar the international system off its positive course.

They did not intervene in the Soviet Bloc’s travails, for example, even when short-term political gain seemed ripe for the taking with just a few short words of support for prodemocracy rallies, and not even when criticized for seeming indifference to the mass protests catalyzed by Mikhail Gorbachev’s programs of perestroika and glasnost. Awful images of Tiananmen Square remained fresh in Bush’s mind, when hope for democratic change quickly turned to desperation and death once government officials determined they’d heard enough from protesters and from their supporters around the world, the American president in particular. Bush’s mild support of the prodemocracy rallies had not triggered the crackdown in Beijing. But Chinese officials nevertheless employed his words to justify their actions as a defense against foreign interference, and later as the reason behind Beijing’s ensuing anti-Americanism. The crowds that formed in East Germany only a few short months later therefore naturally triggered fears of similar treatment, not least because the East German government had made a point of inviting Chinese police officers to teach their own all they could about “crowd control.” History, Bush feared, seemed about to replay.

He therefore chose to do and say as little as possible, in part out of fear of catalyzing a new communist crackdown, and to an even larger extent because he felt the best odds of democracy’s success came from his simply letting events play out. Warning Beijing against cracking down had done nothing. Thus similar warnings were never issued to East Germany. More importantly, neither did Bush too overtly praise the protesters no matter how much he sympathized with their cause, because they had something far more important than an American president on their side: history.

“What I also recall is his understanding that the relationship was complex and that it was tragic but that the entire relationship could not be defined by—We could not afford to let the relationship be defined by that tragic incident. We had to find a way to engage, to allow face-saving. That was very unpopular among many in Congress and many in the White House.”

“I keep hearing critics saying we’re not doing enough on Eastern Europe,” he explained to his diary. “Here the changes are dramatically coming our way, and if any one event—Poland, Hungary, or East Germany—had taken place, people would say this is great. But it’s all moving fast—moving our way—and [yet] you’ve got a bunch of critics jumping around saying we ought to be doing more. What they mean is, double spending. It doesn’t matter what, just send money, and I think it’s crazy.” It had been precisely five months since the bloodshed at Tiananmen, yet the events of those nights, and more importantly the fear that his own actions had somehow contributed to the violence, weighed heavily on his mind. “If we mishandle it [Eastern Europe], and get way out looking like [promoting dissent is] an American project,” he continued, pouring his fears into his tape recorder, “you would invite crackdown, and…that could result in bloodshed.” Things were moving their way, but could still easily veer dangerously off course, or reverse.

Written the night before the Berlin Wall unexpectedly fell, the timing of this sentiment is particularly illuminating. No one expected the breach. The wall opened largely by accident, though the faltering East German regime lacked the power to close it ever again. Bush consequently got what he wanted—greater democratization in Eastern Europe—without doing or saying anything that might have thwarted this desire, because he rightly perceived things already “moving our way.” Guided by a profound sense of democracy’s universal appeal, and witness to its apparent triumph behind the Iron Curtain, Bush reasoned that when the stream of history carried your ship of state in your preferred direction, one should let it.

When the Berlin Wall fell in November 1989, it was largely unexpected.

Even when criticized. “We’re seeing it move, aren’t we?” he quickly retorted when a reporter asked for the umpteenth time why his White House was not doing more to openly support the region’s democratic transition. “We’re seeing dynamic change, and I want to handle it properly.” Pundits and legislators could propose almost anything without consequence. He was ultimately responsible, and he knew “the United States can’t wave a wand and say how fast change is going to come to Czechoslovakia or to the GDR.” Anger finally burst through when another query began: “Your administration has been criticized—” Its author was quickly cut off. “I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and I knew how I wanted to go about doing it,” Bush blustered. “And that’s why I didn’t need the advice of others in this particular subject matter. I knew how I wanted to do it.”

Not acting precipitously did not mean not acting at all, as two examples from Bush’s first year demonstrate. First, Bush did nothing to precipitate the Berlin Wall’s collapse, but did much behind the scenes in its aftermath, engaging in marathon telephone diplomacy with European leaders, including Gorbachev, to ensure that each strove to keep any ensuing chaos or unrest at bay. With the stream of history moving in his direction, in other words, he paddled hard only to avoid rapids, working quietly and largely without public notice when others might have sought greater credit. “I’m not going to dance on the Berlin Wall,” Bush told aides in response to critics who charged he should do more to celebrate this apparent Cold War triumph. The last thing he wanted to do was to “stick a finger in Gorbachev’s eye,” or catalyze a communist backlash.

“[George H. W. Bush] understood that if he had [taken credit for the fall of the Berlin Wall], he would have provoked a different response from Gorbachev. He understood about, How do we help Gorbachev save face and unwind this thing in a way that is responsible and doesn’t require him to get his back up, doesn’t push him up against a wall and invite some response other than a peaceful unwind of this thing?”

Bush’s team also used their first months in office to think. Most administrations want to hit the ground running, showing their mettle or righting all the wrongs they’d been elected to fix. Even though they followed a Republican president into office, Bush’s team did not think of themselves as merely Reagan’s third term. “This is not a friendly takeover,” Secretary of State designate James Baker announced soon after his friend’s election, demanding resignations from every one of Reagan’s appointees so Bush would have free rein to make his own appointments. More than just bureaucratic policies drove this decision, as Bush’s inner circle also thought Reagan’s team had been too trusting of Gorbachev and potential Soviet reforms. “Don’t you think you all went too far?” Baker asked during his first visit to Foggy Bottom.

They didn’t immediately change course, however, instead initiating a lengthy “pause” in Soviet-American relations while launching a full top-to-bottom review of their nation’s foreign policies. “The jury is still out” on whether or not the U.S. should really trust in perestroika, Bush said, and whether Gorbachev’s new spirit of cooperation was merely a Machiavellian “peace campaign” designed to wean Western Europe from Washington’s sphere of influence without firing a shot.

When George H. W. Bush came into office, he and his inner circle did not rush into action but took time to reassess policies.

The pause worked, providing time to think and assess, leading ultimately to a reversal of Bush’s own uncertainty. “Look, this guy IS perestroika,” Bush told his staff by the fall. Let’s not do anything to make Gorbachev’s life harder, he consequently instructed, finding ways to give him a helping hand without doing anything to exacerbate the rising opposition the Soviet leader faced at home. The aforementioned events of November 1989 in East Germany seemed to validate his earlier conclusion. Watching once-unfathomable televised images of the Berlin Wall’s breach, Bush turned to Brent Scowcroft, his national security advisor, and said, “If they are going to let the Communists fall in East Germany, they’ve got to be really serious.”

President George H. W. Bush came into office uncertain about Gorbachev and the Soviet reforms but gradually came to believe in his efforts.

There are two keys to understanding this overall reaction. First, as noted, Bush did not act rashly because he perceived his side already winning. Second, and of equal importance, he perceived no good policy options he might pursue in any event. The White House could have just as easily sent a battalion to the moon as they could have directly supported an armed humanitarian intervention in the heart of China’s capital (and to be clear, no one suggested this course). Neither could direct force or direct aid be employed behind the Iron Curtain, where the Warsaw Pact retained millions of troops. Presidents had helped spur uprisings before, during the 1956 Hungarian revolution for example, only to realize the costs of support were subsequently more than they could bear. Hungary was “as inaccessible to us as Tibet,” Dwight Eisenhower complained, adding that any attempt to deliver aid to Hungarian insurgents was sure to lead to a broader Soviet-American conflict, perhaps even a nuclear one. “Those boys” in the Kremlin were “furious and they’re scared” at the prospect of their newfound empire unraveling, Eisenhower reluctantly concluded. “And just as with Hitler, that’s the most dangerous state of mind they could be in.” Bush, who not coincidentally took Ike as his presidential role model, might well have said the same thing when confronted with his own turmoil in Eastern Europe.

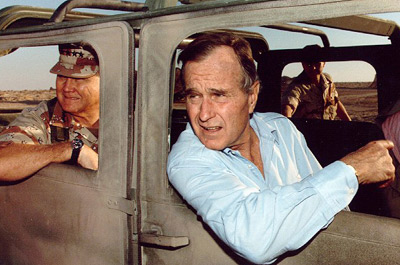

In 1990, President Bush ordered more than half a million troops into the Middle East to counter Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait.

We should not think Bush wholly incapable of action merely because he so effectively demonstrated restraint during his first year in office. This was the president, after all, who subsequently moved more than half a million troops to the Middle East to reverse Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait. “I feel great pressure, but I also feel a certain calmness,” Bush wrote of his decision. It had taken days, but he knew “what can be done and how long it will take.” Ultimately, because he had a clear option before him, because the moral and political issues at stake seemed clear, and in the final analysis because unlike the prodemocracy movement in Eastern Europe the situation in the Middle East would not resolve itself without American leadership, Bush concluded that “I know I am doing the right thing.” It was “only the United States that can lead” in situations like these, he later said—not only because they were the strongest, but also because the situation was right.

Taken collectively, therefore, Bush’s first year in office offers an incoming administration three lessons.

“We didn’t have the backbiting and backstabbing and leaking on each other. We didn’t have that. We worked as a team. And I wrote that the main thing was the leadership of our president, because he knew how [the national security team] ought to work.”

First, do no harm. For all its ups and downs, the American system works better than any other potential peer or competitor. Then, as now, the United States remains the world’s dominant economy and cultural center. Then, as now, it is the hub of dynamic innovation, especially on the technology front. Then, as now, the American military largely guarantees the safety of the global commons. Then, as now, the democratic ideals it espouses resonate throughout the world. Yes, problems exist, wicked problems lacking clear-cut solutions instigated by evil men with little to commend them. But when the world is moving in Washington’s general direction…let it.

Second, take time to reassess policy, rethink convictions, and reshape the national security bureaucracy to your liking, noting even when reconsidering a predecessor’s apparent mistakes that your peers from the previous team might well have been right after all. Taking the time to make the assessment yourself, however, helps make this determination your own.

President Bush took his time to consider his predecessor’s approach to foreign policy and to build a national security team that worked well together.

Third, take time before implementing solutions. Bush’s team bungled a series of crises in their first year, most famously their failure to provide even minimal support to plotters eager to remove Manuel Noriega from power. Information was stove-piped and jealously guarded, leaving crucial bits of data unavailable to everyone in the decision-making loop, and ultimately leaving Bush to wonder about Noriega’s fate a full six hours after Defense Secretary Dick Cheney and Joint Chiefs Chairman Colin Powell knew of his return to power. It was Powell’s first week on the job, in fact, and he could hardly have made a worse first impression.

Critics howled at the administration’s apparent incompetence, demanding the removal of Cheney or Powell, perhaps both. Bush refused to fire anyone, however, giving them instead time to refine their organizations for future crises while emboldening Scowcroft to streamline the administration’s overall emergency management approach. Having taken the time to select good people, Bush believed it important to give subordinates, and old colleagues in particular, the opportunity to learn how best to work with each other from their new positions and departments. Every subsequent incoming administration has stated its intention to follow Scowcroft’s model, but it is important to note that the model they hoped to emulate was that of 1990 and 1991, and not of the Bush team’s less impressive first year. It was during that first year, however, though not in its first iteration, that the model was formed.

“One of the nice things about working for George Bush in the intelligence field is that uniquely among Presidents he knew the strengths and limitations of intelligence and he knew what could be done, what couldn’t be done. He knew that all they could tell you is that the army is there and it is ready and it could go within a matter of hours, if they chose to do so. Whether they chose to do so is unknowable.”

In the final analysis, Bush’s example teaches prudence. Prudence is an overused word when describing George Bush’s foreign policy, thanks in particular to comedian Dana Carvey. It is, nonetheless, the ideal word. Prudence requires caution, judgment, experience, and patience. It does not preclude one from acting. Neither does it allow for reckless decisions. Rather, the prudent leader realizes that less is more when the world is moving your way, and that action, when necessary, is best done consciously and intentionally. It means allowing good people time to think and to do their jobs, and recognition that the best leadership can come from doing nothing at all. Or, as Bush noted in his diary as his one-year anniversary in office neared: “The longer I’m in this job, the more I think prudence is a value and experience matters.”