Financial crises happen when you least expect them, including soon after a new president takes office. Containing a crisis can require quick decision making and action before the new administration has accrued significant experience. Addressing it may require the president to put aside other policy priorities to which much attention was devoted during the electoral campaign. It can require smooth relations with Congress at a time when such relations are not yet deep. It can require cooperation with foreign governments and leaders before there has been time for introductions, much less for the development of relationships.

Barack Obama inherited the economic crisis that began during the presidency of George W. Bush.

A new president can be faced with an economic and financial crisis for different reasons. Barack Obama had inherited his crisis: It erupted on the watch of his predecessor, George W. Bush. That earlier administration, together with the Congress, had failed to take adequate steps and lacked time to resolve it, therefore bequeathing it to their successors. Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 both inherited and created his crisis. The Great Depression was underway well before the election and, for that matter, before the campaign, and the Hoover Administration, together with the Congress, failed in its efforts to contain it. But the president-elect hesitated to clarify his intentions in the then four-month interregnum between election and inauguration, causing investors to fear dollar devaluation and pull their money out of the country.

The experiences of FDR and Obama suggest clear “dos and don’ts” for newly elected presidents confronted by an economic and financial crisis.

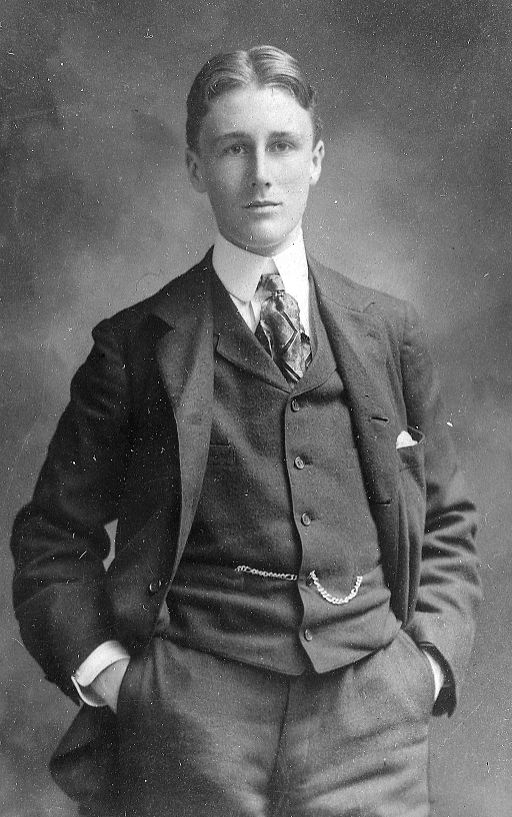

The United States has never had a trained economist as president. Franklin Roosevelt studied history at Harvard before attending law school at Columbia University.

If you think that this points to a gap between the new president’s natural inclinations and what it will take to resolve a crisis, then you’re right.

For better or worse, the United States has never had a formally trained professional economist as chief executive. (Some would argue this has been for better.) FDR was certainly not a professional economist. After graduating from Harvard College in 1904, Roosevelt remained there to study economics, political science, and history before entering law school at Columbia University. But his training in economics was never more than a minor element in his education. With its emphasis on long-run structural issues (the closing of the frontier, the rise of big business), that training was less than immediately relevant to the task of resolving the financial crisis.

Thus, it was important for well-informed and timely decision making for FDR to assemble a team of expert advisers—a team, because no single adviser possesses the requisite range of expertise. It was further necessary for the president to devise a method for focusing their efforts, sifting through their conflicting opinions, and making a decision on further action. Historians have reached mixed conclusions on FDR’s success at managing this process. A Roosevelt adviser, Judge Samuel Rosenman, already encouraged the candidate to gather a group of academic advisers prior to the nomination to help him articulate a response to the principal campaign issue, namely the economic crisis. Rosenman then contacted Raymond Moley, a 46-year-old Columbia University professor of government and public administration (not economics). Moley in turn suggested R. G. Tugwell, an economist; Adolf Berle, a lawyer with interests in economics; and several others. From this seed, FDR’s “Brains Trust” sprouted. These men with diverse backgrounds had diverse views, all of which received a hearing from the candidate. Gathering around him this team of academic thinkers already during the campaign was regarded as a “great innovation” at the time, one that presidential candidates have emulated ever since.

After the election, several members of the Brains Trust were given administrative positions in government agencies. Rosenman criticized this as a mistake, arguing that the president would be better served keeping them available for free-ranging discussion and advice. Be this as it may, FDR maintained the same approach of surrounding himself with advisers with conflicting points of view when appointing cabinet members.

FDR’s mechanism for eliciting advice and information was encouraging free-wheeling discourse and conversation. He encouraged members of the Brains Trust and subsequent advisers and visitors to offer plans and ideas by nodding encouragingly, seeming to agree while all the while keeping his own counsel and prepared to exercise final decision making authority, given his own assessment of political imperatives and constraints.

While continuing to solicit advice and ponder options prior to his inauguration, FDR refused to commit to a course of action. Hoover, now a lame duck, made repeated efforts to get the president-elect to agree to a joint statement and course of action during the interregnum, but FDR refused—a refusal that Hoover blamed for aggravating the banking crisis of early 1933 and worsening the Depression. It is not clear, however, whether FDR had any choice in the matter. The course that Hoover urged—maintaining the gold standard, pursuing a joint agreement at the London World Economic Conference—was not one that FDR had yet decided, or would ultimately decide, was prudent. The president-elect understood that restoring confidence required speaking with a firm, reassuring voice and taking decisive action. It was not clear that a compelling message that there was “nothing to fear” could be sent when speaking as part of a chorus, or that decisive action was possible prior to taking office.

In his first Fireside Chat, President Roosevelt calmed the fears of the nation and outlined his plan to restore confidence in the banking system.

The new president’s priority on entering the White House was necessarily resolving the banking crisis, the first step in which was declaring the Bank Holiday. FDR understood that economic stabilization, much less recovery from a financial crisis, was impossible with an impaired banking system. The president immediately took to the airwaves, using the media to reassure the public that their deposits were safe. There being no time to waste, or even to plan, he built on the plan developed by Hoover’s treasury secretary, Ogden Mills. He utilized the previous administration’s crisis-resolution mechanism, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC), to which he assigned expanded responsibilities.

Recognizing the need to work together with the Congress, FDR summoned the latter into special session, expressly to address the banking crisis. Both houses quickly passed the Emergency Banking Act. This gave legal status to the Bank Holiday; it authorized the RFC to inject capital into banks and not just provide liquidity; and it loosened collateral requirements on Federal Reserve lending to distressed financial institutions, effectively providing an unlimited guarantee of deposits. By the end of the first month of the new administration, the banking crisis was a long way toward resolution.

FDR’s approach to enlisting the Congress is revealing. In calling the special session, he initially gave it a very limited mandate confined to the core issue: addressing the banking crisis. In seeking to elicit its support and induce quick action, he gave it a short, focused piece of legislation: just five titles or sections, and only a handful of pages. Reform of the banking system, which came with the Glass-Steagall Act, was left for two months later. Only later, when the efficacy of the special session had become evident, did FDR extend it and expand the mandate to include other aspects of what became the Hundred Days and the New Deal.

In responding quickly to the banking crisis, FDR was aided by the fact that his party possessed large majorities in both houses of Congress. But even large majorities did not allow the president to respond unilaterally. In formulating policy toward the economic and financial crisis, the predominance of Democrats and presence of populists also posed a constraint. FDR was concerned that populist members committed to inflation might break away from him and from responsible congressional leadership in the absence of decisive, visible action to counter the deflationary threat. The president’s decision in April to place a permanent embargo on gold exports and support the Thomas Amendment, providing for active credit expansion, and then his efforts, under authority granted the RFC, to actively push down the dollar exchange rate by pushing up the price of gold, were taken in response to this perceived danger. Other policies like the crop set-asides of the Agricultural Adjustment Act, which the majority of economists came to regret, can be seen in a similar light.

These references to the dollar and the price of gold flag a final aspect of FDR’s approach to the financial crisis. The Great Depression and 1930s financial crisis, like all serious financial crises, were global rather than national phenomena. Events in the United States infected foreign economies, and vice versa. This recognition had been Hoover’s motivation for calling for a World Economic Conference to be held in 1933. It was similarly the instinct of many in FDR’s own circle. By refusing to seriously pursue an international agreement at the conference, FDR antagonized many of those advisers. By issuing his famous “bombshell message” denigrating exchange rate stabilization as one of the “old fetishes of so-called international bankers” in the midst of the conference, he was widely criticized for eliminating all residual scope for an international cooperative response.

Eventually, most major governments adopted the same response as the United States to the Great Depression. They abandoned the gold standard, which enabled their central banks to cut interest rates and provide desperately needed credit to the banking and financial system, and through that channel, to the rest of the economy. As central banks cut interest rates, their currencies declined on the foreign exchange market, which enhanced the competitiveness of their exports but excited complaints of “currency manipulation” (to use the modern terminology) from the rest of the world. Trade conflicts and political conflicts were exacerbated.

But as other countries responded in kind, the initial configuration of exchange rates was essentially restored. Each of the countries involved now benefited from lower interest rates, putting an end to deflation and helping to stabilize their banking systems and their economies. The problem was that this happy result had been achieved only at the end of a period of high uncertainty and international recrimination, which were not good for economic stabilization and recovery. Better would have been if different governments had been able to cooperate by implementing the same steps simultaneously. But Roosevelt, in his wisdom, was not willing or able to persuade them.

The economic and financial crisis was the defining issue of the 2008 election and of 2009, the first year of the Obama Administration. The pressing nature of the financial crisis was already apparent in the summer of 2008, although it became transparently clear following the failure of the investment bank Lehman Bros. in mid-September.

President Barack Obama did not have formal training in economics so he assembled a diverse team of economic specialists to help him navigate the economic crisis of 2008.

Like FDR, Obama did not have extensive formal training in economics, so like FDR he moved early in the campaign to surround himself with an eclectic group of advisers. Initially his advisers were mainly family, friends, and longtime associates such as the political operative David Axelrod. Economic expertise was thinly represented; Obama, a Chicago native, enlisted a younger University of Chicago professor, Austan Goolsbee, with wide-ranging interests but limited expertise in macroeconomics, banking, and finance. Recognizing the centrality of the economic and financial crisis for the campaign, he then assembled a diverse team of economic specialists. There were the Robert Rubin protégés (Jason Furman, Lawrence Summers, Timothy Geithner), with Rubin playing the same role in stocking the administration-to-be as had Felix Frankfurter in 1933. There were the progressives (Robert Reich, Jared Bernstein). There were independents who did not obviously fall into any of these categories but had stature or relevant expertise (Paul Volcker, Christina Romer). Importantly, some of these advisers had been involved in helping to manage the Mexican financial crisis in 1994 and the Asian financial crisis in 1997–98. Others were experts on the history of earlier financial crises.

Like FDR, Obama sought a diversity of views. He encouraged debate, in which he was a more active participant than the frequently nodding FDR, although he also displayed more impatience with the failure of his advisers to reach a consensus. What started as once-every-five-days telephone briefings during the campaign turned into four-mornings-a-week economic briefings with the inauguration. Where FDR had loaded down a number of Brains Trusters with heavy administrative responsibilities, Obama kept a number of them (Summers, Romer, Bernstein) as policy coordinators and advisers in the White House.

In contrast to Roosevelt, Obama did not refuse to cooperate with the outgoing administration on financial policy prior to his inauguration. He supported the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) during the campaign and lobbied for release of its second $350 billion tranche during the interregnum. It can be argued that this was the responsible approach: Money for bank recapitalization was urgently needed. The window during which an increasingly angry Congress would support funds for recapitalization was closing. It might be easier to get the Congress to release already-appropriated funding, the Obama Administration reasoned, than to vote later to fund a new program. But in supporting this Bush Administration initiative, Obama was also constrained in his ability to criticize his predecessor’s approach to managing the financial crisis. This inability to assign blame meant that his political opponents were better able to place significant responsibility for the crisis on Obama’s own shoulders. His failure to assign blame was something that Obama subsequently came to regret.

Also unlike Roosevelt, Obama did not focus on the banking crisis, instead devoting equal attention to a range of other issues including macroeconomic stimulus and health care reform. (FDR, in contrast, had waited until 1935 for Social Security, his signature social legislation.) This difference had a number of aspects. First, there was the development in the intervening 80 years of macroeconomic analysis and policy, which pointed to the need for fiscal stimulus to counter the slump. There was no analogous body of knowledge about the need for a stimulus package in 1932. FDR himself was a fiscal conservative and believer in balanced budgets. Obama similarly had conservative fiscal instincts, to which he succumbed in 2010 when the debate turned to the pace of fiscal consolidation. But he did not question the need for a substantial fiscal stimulus package in 2008–09. This was a priority to which he devoted considerable time and effort, seeking to get a stimulus bill signed on his first day in office.

Historians continue to debate the Obama stimulus. Some criticize it as too small while others defend it as reasonably sized given what was known about the economy’s rate of contraction at the time. Some dismiss it as ineffectual on the grounds that Obama chose to tilt it toward tax cuts rather than public spending so as to win Republican support, where the tax rebates were banked rather than spent, and the Republicans were simply able to pocket the offer of tax cuts without offering any policy concessions in return. This is part of the more general criticism that Obama was too concerned with preserving bipartisanship at a time when the Democrats had majorities in both houses of Congress.

On the spending side, some criticize the Obama stimulus as focusing excessively on shovel-ready projects and neglecting inspiring initiatives like the Grand Coulee Dam that would have taken longer to complete, while others defend it on the grounds that the extended nature of the slump, which created time for high-profile “signature” projects, could not have been anticipated at the time. My own view is that more emphasis on the public-spending side, less attention to shovel-ready projects, and above all a larger stimulus would have been better. But that is the conclusion of an economist. Obama’s political advisers argued that the Congress would be reluctant to pass a larger stimulus and that proposing one might damage the administration and the president. Their arguments carried the day.

As well, there was Obama’s reluctance to put the rest of his policy agenda on hold. He had campaigned on a platform of health care reform and other progressive social policies that he was reluctant to set aside. Avoiding a financial catastrophe was not enough for a new president with greater ambitions. Obama and his advisers subscribed to a “big bang theory,” whereby a host of social programs could be passed in a period of extraordinary politics associated with a financial crisis. Hindsight suggests, to the contrary, that passing each of these programs, health care for example, absorbed political capital that might instead have been husbanded for measures to resolve the economic and financial crisis.

President Obama's Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner argued that aggressive intervention and criticism of banks would damage confidence in the financial system and hinder recovery.

Team Obama’s management of the banking crisis similarly remains controversial. There was disagreement at the time about how hard to come down on the banks: whether to require of them significant amounts of new capital, thereby forcing those unable to raise it to take it from the government, de facto nationalizing them, or whether to proceed on the assumption that the banks were still solvent, pointing to limited new capital needs that could basically be raised on the market. Treasury Secretary Geithner argued the second position; prominent private sector economists and, at some points, National Economic Council Chair Summers argued the first. Geithner maintained that more aggressive intervention and criticism of the banks would damage confidence in the financial system and hinder recovery. His critics countered that without swift and forceful recapitalization, vigorous economic recovery was impossible.

In the end a compromise figure of $75 billion of new capital was agreed. Nationalization was avoided, and the banking system recovered. It can be argued that Geithner was right in his assessment that the banks were illiquid but not insolvent. But it can also be argued that there was more than a little smoke and mirrors involved, as in 1933. In 1933, the reality was that it was not possible to really do a careful evaluation of the solvency of each and every individual bank during a two-week holiday. But the claim that the Federal Reserve would be carefully scrutinizing the banks, together with enhanced powers to provide liquidity under the Emergency Banking Act, had been enough to dispatch the panic. In 2009, Geithner’s stress tests of the banks were perhaps less scientific than purported when it came to determining their capital needs. But the belief that the government was again on the case and the conclusion that new capital needs were neither too small to be credible nor too large to be obtainable were enough to contain the crisis. Effective resolution of a banking crisis requires concrete policy intervention, but it also requires effective public relations to persuade the public that there is nothing to fear but fear itself.

President Obama cooperated closely with foreign leaders in seeking to manage the financial crisis, including attending the Group of Twenty summit in London in 2009.

In contrast with FDR, Obama cooperated closely with foreign leaders in seeking to manage the crisis. There were ongoing telephone consultations and a high-profile Group of Twenty summit in London in February 2009, where governments committed to coordinating their policies, shunning protectionism, and undertaking $1 trillion of fiscal stimulus. Avoiding protectionist responses was a valuable achievement, although it can be argued that doing so is easier when other measures are utilized to expand demand so that efforts to bottle up a fixed lump of spending at home become less pressing.

In addition, with the tacit approval of the administration, the Federal Reserve extended four $40 billion credits (technically swap lines, under which dollars were swapped to foreign central banks for their respective currencies) to four emerging markets (Mexico, Brazil, South Korea, and Singapore), and even larger credits to the central banks of Canada, England, Japan, Switzerland, and the Euro Area. Providing dollar credit to these foreign central banks was critical, since the global banking system—and not just the U.S. banking system—runs on dollars. Foreign central banks have limited dollars of their own, so they would have had limited capacity to intervene and stabilize their banking systems without the Fed’s swaps. These efforts at international cooperation thus played an important role in resolving the crisis, both by providing dollar credit where dollar credit was needed and as a confidence-building measure.

Imagine that the 45th president of the United States experiences a serious banking and financial crisis early in his administration. What lessons should he draw from how his predecessors handled similar events?

First, it is essential for the president to take advice from persons with demonstrable economic and financial expertise. While banking and financial crises have political aspects, they also have complex, technical economic dimensions. Individuals experienced in dealing with them and able to characterize events in nontechnical terms can help the president reach informed decisions that balance the costs and benefits of alternative courses of action. This doesn’t mean relying only on PhD economists for advice, but it does mean assembling a team of advisers that includes not just businessmen, hedge fund managers, and trade economists but also individuals with this specialized macroeconomic and financial training. Trump’s early circle of advisers is notable for the absence of professional economists with demonstrable expertise in macroeconomics and finance, not to mention persons familiar with financial crises that have taken place earlier in U.S. history.

Second, entertain different points of view. The complexity and fast-moving nature of financial crises means that there will not be clarity and agreement on how to proceed. Different considerations—stabilizing the financial system and the economy versus not rewarding reckless behavior and not setting the stage for more risk taking and crises in the future—will have to be weighed against one another, and the terms of trade will be unclear. The president should hear different views of the nature of these trade-offs before reaching a judgment and settling on a course. Although advisers to Obama and FDR were criticized for not embracing a sufficiently diverse variety of viewpoints (both presidents were criticized for not listening to enough progressive advisers), each made visible efforts to incorporate economic advisers with different points of view. This kind of intellectual diversity is not an obvious feature of Trump’s initial group of advisers.

Third, focus first on resolving the financial crisis—the most pressing order of business— and put the rest of the policy agenda on hold. The experience of the Obama Administration, and the contrast with FDR, suggests that attempting to use the crisis as an opportunity for extraordinary politics is likely to be counterproductive. Even a new president still on his political honeymoon has limited political capital. Allocating that capital to the most pressing priority, in this case resolving the financial crisis, avoids dissipating it on issues that can wait.

Fourth, the midst of a financial crisis is no time for off-the-cuff statements or Twitter messages. Statements that excite financial markets can aggravate the damage from a crisis and create irrecoverable costs. Both FDR and Obama understood the role of the president in providing reassurance and acting as a calming influence in the midst of a crisis.

Fifth, recognize that financial crises are not just national but international events. Financial crises spill across borders. Even if they originate in the United States, they infect other countries, and events there can then spill back to the United States. Attempts to resolve a crisis without cooperating with foreign governments are costly or impossible. Resolution of the 2008–09 crisis, for example, was greatly expedited by the decision of the Federal Reserve to extend multibillion-dollar credits to foreign central banks, and by agreement among governments, including that of the U.S., at the February 2009 summit of the Group of Twenty in London to coordinate their national programs of fiscal stimulus. If faced with a serious financial crisis, the new president will have to establish lines of communication and good relations with foreign governments, and he will have to encourage the Fed to cooperate with foreign central banks. This may not be his natural inclination, but succumbing to that natural inclination would be disastrous.