The passage of Medicare and Medicaid represented one of the most significant accomplishments of Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. Together, they formed critical components of perhaps the most successful “first year” presidency in U.S. history. Careful review of the process through which the Johnson administration shepherded the legislation through Congress offers key lessons for the president who will take office in January 2017.

When Lyndon Johnson took over the presidency in November 1963, critical shifts had already taken place in the debate over health care policy in the United States. Following the defeat of President Harry Truman’s proposals for national health insurance at the hands of congressional conservatives allied with the American Medical Association, reformers focused on achieving health coverage for elderly Americans, rather than for the population as a whole. The elderly represented an inherently sympathetic constituency, and the Social Security system provided a familiar mechanism for their coverage. Meanwhile, through the 1950s, labor unions, corporations, and commercial insurers expand the employer-based health insurance. By the early 1960s, roughly 70 percent of Americans had some form of coverage through this “insurance company model,” a development that further reduced pressure for national health insurance.

During the 1960 campaign, John Kennedy called for a Social Security-based program of federal health insurance for the elderly, an idea his campaign called Medicare.

Yet the elderly, who proved to be poor risks for insurance companies, remained largely outside this private coverage system. In 1960, House Ways and Means Committee chairman Wilbur Mills and Senator Robert Kerr sponsored a limited measure that provided federal matching grants to the states to cover low income seniors. Not all states took up the program (popularly known as Kerr-Mills), and its effectiveness remained limited. During the 1960 presidential campaign, John F. Kennedy called for a Social Security-based program of federal health insurance for the elderly, an idea that his campaign referred to as Medicare.

In January 1962, late in the first year of his presidency, Kennedy submitted his Medicare proposal to Congress. Known as the King-Anderson bill after its chief sponsors, Kennedy’s Medicare bill covered hospital and nursing home expenses for recipients of social security and disability, but did not include coverage of physicians’ fees. Mills, one of the most influential policy figures in Washington, opposed the bill. The Kerr-Mills Act had just taken effect, and Mills did not want to undermine it by passing Medicare. He also feared that financing the new program through the payroll tax might jeopardize the long-term fiscal viability of the existing Social Security system. The AMA, meanwhile, remained uncompromising in its opposition and launched an all-out lobbying campaign, which included the distribution of anti-Medicare recordings made by actor Ronald Reagan. The Ways and Means committee held hearings but never voted on King-Anderson. This pattern repeated itself when the administration re-introduced the bill in 1963.

The Kennedy administration used these defeats strategically, publicizing the nature of the AMA’s opposition and seeking to build public support for a renewed effort later in Kennedy’s term. Significantly, Kennedy also influenced new appointments to the Ways and Means committee: All new members of Ways and Means either supported Medicare or would at least vote to report it to the floor. One potential lesson for a first year president thus rests in the Kennedy role in Medicare’s ultimate passage: Even in defeat, look for opportunities to create future legislative opportunities.

`Taking office after President Kennedy’s 1963 assassination, Lyndon Johnson followed a similar strategy. During 1964—what might be called LBJ’s “first first year”—the president made an intensive push for Medicare, but ultimately fell one vote short of a majority on Ways and Means. Along with congressional liaison Lawrence O’Brien and Assistant Secretary of Health, Education & Welfare Wilbur Cohen, President Johnson worked extensively during this period to win over Wilbur Mills. In part, Johnson did this by suggesting that Mills would receive the credit for passing a Medicare bill, but also by indicating that the administration would be open to options other than King-Anderson. Mills feared that because King-Anderson as written covered only hospital and nursing home costs, seniors might be disappointed when they discovered that Medicare did not cover doctors’ bills—and that they would blame the Democratic Party. As early as January 1964, Mills suggested the addition of physician fees to Medicare. In June 1964, Mills and Johnson discussed a package that would combine hospital and physician coverage with the existing Kerr-Mills program.

This would be the ultimate model for the legislation that, nine months later, created both Medicare and Medicaid. Although the Johnson administration lost the 1964 debate, the president and his team created conditions that would facilitate later success—on an even grander scale than the original proposal.

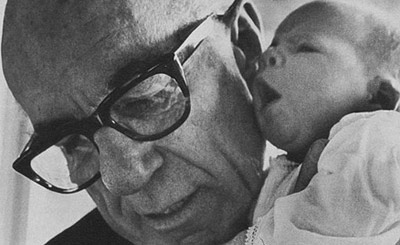

President Johnson’s support for Medicare, which a majority of the public now supported, contributed to his landslide victory in the 1964 election. A few days before the election, Doctor Benjamin Spock (famous for his wildly popular parenting manual) called to congratulate the president. He also relayed an account of his appearance on the ABC News public affairs show Issues and Answers, highlighting the panic that now gripped both Republicans and the AMA over Medicare.

The president’s lengthy coattails also brought large Democratic majorities to Congress. This fundamentally shifted the political situation facing Medicare. Most significantly, the Ways and Means Committee would have a clear majority in favor of a Medicare bill. A few days after the election, President Johnson discussed the implications with House Majority Leader Carl Albert of Oklahoma.

When Johnson took the oath of office for his “second first year,” Medicare’s passage thus seemed certain, but its exact form remained unclear. The 1965 amendments to the Social Security Act constituted the battleground for the bill: The administration initially proposed the standard King-Anderson package of hospital and nursing insurance financed by an additional Social Security payroll tax. Moderate Republicans, desperate to recapture the political center after the Barry Goldwater debacle, attacked Medicare for its lack of coverage for physician services (as Wilbur Mills had anticipated). Wisconsin Representative John Byrnes, the ranking minority member of Ways and Means and a widely respected Social Security expert in his own right, offered a proposal that the Republicans dubbed “Bettercare.” It provided coverage of both physician fees and drugs, with participation voluntary. Financing would be entirely outside the Social Security system, through general tax revenues and participant contributions. Bettercare sought to break the Republican identification with the AMA and to peel off the votes of moderate and conservative Democrats.

Meanwhile, the increasingly desperate AMA sought to stave off both Medicare and Bettercare with a more limited proposal to extend the Kerr-Mills program for low income seniors. The AMA designated their program as “Eldercare.”

The AMA also relaunched its standard attack on Medicare as “socialized medicine,” but by 1965, the doctors’ organization had lost much of its former influence. The public had come to see the organization as simply an interest group, rather than as the legitimate voice of medical authority in the United States, and no longer responded to AMA warnings about creeping socialism.

At a more strategic level, the AMA’s continued intransigence so irritated Mills that he refused to even consult AMA representatives in closed sessions of the Ways and Means committee. Increasingly, some doctors began to defect from their professional organization’s position, both because they saw little real harm in providing medical coverage for the elderly and because they had become comfortable with accepting payments from commercial insurers. Finally, even the AMA’s supposed allies in the insurance industry were not really with them. Although the Health Insurance Industry of America still officially opposed the Medicare legislation, its member companies were happy to offload an unprofitable industry segment (offering health insurance to illness-prone senior citizen) onto the federal government. The non-profit Blue Cross plans had begun negotiating years before for a role administering an eventual Medicare program, and the rest of the industry joined that effort as passage seemed likely in early 1965. As a result, the HIAA publicly supported the AMA position, but never fully mobilized against Medicare.

The respective positions of the AMA and HIAA suggest a principle that first-year presidents should continually pursue: Whenever possible, search out ways to appeal to opponents’ own interests, and failing that, seek to isolate them.

With the Republican “Eldercare” bill gaining traction in the House, Wilbur Mills made a dramatic move during closed Ways and Means Committee hearings. Previously, the Republican, AMA, and administration bills had all been assumed to be mutually exclusive, even though they covered different aspects of medical care. With a flair for the drama that only social policy allows, Mills suddenly mused: “Well now, let’s see. Maybe it would be a good idea if we put all three of these bills together”—and ordered Wilbur Cohen to draft such a bill by morning. This “three-layer-cake,” as it came to be called, formed the basis for the modern Medicare and Medicaid systems.

In June 1964, President Johnson and Wilbur Mills discussed a package that would combine hospital and physician coverage with the existing Kerr-Mills program.

The move stunned veteran observers of Ways & Means. Historians disagree over whether Mills and Johnson had secretly planned the three-layer-cake strategy. Yet the conversation from June 1964 captures the two discussing the prospects for such a combination, and Mills later recalled that “we planned that, yes.” While this comment likely overstates the level of direct coordination between Mills and the White House, Lyndon Johnson had clearly indicated that he would accept new solutions to the Medicare challenge. When Mills saw the opportunity, he felt free to take it.

Cohen and other Social Security experts immediately redrafted the bill according to Mills’ instructions. The King-Anderson Bill became Medicare Part A, covering hospital and nursing home charges through a new payroll tax (as well as a broadening of the wage base on which the payroll taxes are levied). Mills tried to ensure clear actuarial soundness for the overall program and also insulated Social Security from Medicare by creating a separate trust fund for the latter. The two explained the final structure to Johnson in a conversation on March 23, 1965.

As passed, Medicare and Medicaid reflected the ideas not only of the administration but also of Wilbur Mills, moderate Republicans, and even the AMA. This suggests that first-year presidents can develop new policy opportunities if they remain open to changes in approach, particularly through the cooptation of opponents’ ideas.

Medicare and Medicaid represent two of Johnson’s most important legacies. Medicare in particular has done more than any other federal policy to lift seniors out of poverty and assure dignity and a modicum of comfort in old age. But the program also created long-term budgetary challenges that have plagued every president since Johnson. Today, health care represents one of the largest and fastest-growing sources of federal spending. A 2010 Peterson Foundation report on the long-term fiscal crisis emphasized that “any long-term plan to stabilize the national debt as a percentage of the overall economy will depend on successfully controlling the costs of federal health programs.”

Dr. Benjamin Spock, author of a widely popular parenting book, called President Johnson to congratulate the president on his support of Medicare.

Medicare and Medicaid are expensive because they are intertwined with the larger U.S. health care system, which has cost levels that vastly exceed those of other developed countries (Medicare actually has somewhat lower cost levels than private insurers). This outcome reflects Johnson and Mills’ choices about the basic structure of the program. Seeking to avoid further alienation of the AMA, Medicare did not provide effective controls on physicians’ fees. Instead, it left the determination of reasonable charges up to physicians in conjunction with insurance companies (which gained a profitable role in Medicare claims administration). Wilbur Cohen explained this to Johnson as he summarized the overall benefits in the bill.

Hospitals received a similar degree of pricing deference. Over time, this latitude contributed to the excessive rate of cost inflation in the wider health care system. Such costs now threaten the actuarial soundness of Medicare and Medicaid as well as the overall federal budget.

In 1965, Johnson and Mills lacked the precise, long-range forecasts that the Congressional Budget Office now provides. Nonetheless, both understood that the new programs would have significant and unpredictable long-range costs, but they chose to emphasize the short-run affordability of the program. The president made this point to Mills during the March 23 conversation.

The immediate costs would be manageable; the problem lay in the way that Medicare and Medicaid embedded the larger system’s cost structure in its basic incentives and financial architecture. This suggests that politics aside, first-year presidents must consider the long-range implications of health care policy choices. The real benefits of such policies must be balanced against the problems they will generate for future presidents.

While Republicans in the House still preferred John Byrnes’ Eldercare plan (and came within 23 votes of passing it during a late tactical maneuver), most did not oppose the final three-layer-cake of Medicare and Medicaid. Mills’ endorsement, in turn, brought the votes of many conservative southern Democrats. The bill cleared the Ways and Means Committee and passed in the House on a vote of 313 to 115 on April 8. The Senate passed a version with expanded benefit levels that added $800 million in costs to the bill, but Mills led a coalition of fiscal conservatives that knocked out most of these amendments in conference committee.

Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Wilbur Cohen worked extensively with President Johnson to craft the legislation that became Medicare and Medicaid.

On July 27, both the Senate and House passed the conference committee bill. Three days later, President Johnson signed the bill in the presence of Harry Truman at the former president’s library in Independence, Missouri—paying tribute to the president who had proposed the first federal health insurance legislation nearly two decades before.

Lyndon Johnson did not micromanage this legislative process. Instead, he deferred details to knowledgeable surrogates such as Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Cohen, who in turn worked with Mills to craft both strategy and specific legislative points. This allowed the president to exert his influence when needed, while providing a useful degree of separation from the immediate pressures of the policy process. A conversation with West Virginia Senator Robert Byrd, in which President Johnson sought to avoid a commitment to lower the Medicare eligibility age to 60, captured this dynamic.

The passage of Medicare and Medicaid thus demonstrates the importance of identifying and relying on key personnel both inside and outside the administration. On an inside basis, the first-year president should find a Wilbur Cohen (preferably along with a Lawrence O’Brien): talented and knowledgeable subordinates to manage the details of the legislative and policy development process, allowing the president to save direct interventions for critical moments. Outside the administration, the first-year president should find a Wilbur Mills: pragmatic Congressional leaders, some of whom may even begin in opposition, with the credibility to bring their colleagues into line, and an openness to building long-term alliances.

The persistence of the Kennedy and Johnson administrations in pushing Medicare year after year, despite repeated failures, contributed to building the political conditions that won over Mills and the Ways and Means Committee to the Medicare cause. More than just persistence, this reflected the manner in which Medicare met a pressing need among the American people. This suggests a third lesson for new presidents: Identify issues and policies that will appeal to real areas of concern among the broad public, and then do not give up.

In 1965, President Johnson signed the Medicare and Medicaid bill with former President Harry S. Truman by his side.

Johnson emphasized this determination in a conversation with his new vice president, Hubert Humphrey.

Through these techniques, the administration created conditions under which Mills could move the legislation forward by incorporating both the Republican and AMA positions in a way that made it difficult for either to block the final bill. This produced a more expansive program and a historic first-year victory for the Johnson administration. Like all such achievements, the passage of Medicare reflected the particular historical contingencies of its time. The broad principles of its success, however, can nonetheless be useful for the new president in 2017.