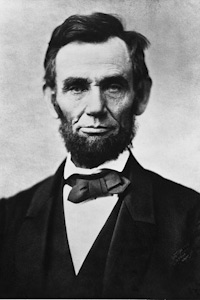

Abraham Lincoln experienced a unique initial year in the presidency. No other incoming president has faced a comparable challenge to the stability of the country. Because of the special circumstances in 1861, no candidate in 2016 should be compared to Lincoln. Yet there are broad parallels between his first year as president and our current political situation. In both instances, national party structures suffered internal fracturing, though it remains to be seen whether either of the current major parties matches the Democratic Party’s collapse in 1860-61.

A second parallel lies in widespread unwillingness to engage in anything approximating bipartisanship, with people all along the political spectrum expecting the worst from their opponents, routinely accusing them of lying, and predicting dire consequences should the election go badly. Finally, the two eras underscore the need to bring different voices to bear on major national problems—in Lincoln’s case, reaching out to Democrats and filling his cabinet with leading figures who held divergent opinions about such issues as emancipation but could be trusted to cooperate in the overriding task of saving the Union.

When President Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address in March 1861, seven southern states had left the Union and established the Confederacy.

Lincoln’s actions illuminate the importance of dealing with the most critical issue or problem and the difficulty of forging policy in the face of opponents loath to trust presidential motives or statements.

When Lincoln delivered his first inaugural address on March 4, 1861, seven states had left the Union and established the Confederacy. The future of eight other slaveholding states remained uncertain, a dangerous situation at Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor simmered, and political divisions within the loyal populace remained deep. Lincoln and members of his party often worked in concert, but sometimes their differences over how best to define the war’s goals, especially pertaining to emancipation, placed them at odds. A large Democratic opposition criticized the president’s use of executive power to suppress the rebellion and distrusted his disavowal of any intention to strike at slavery where it existed under the protection of the Constitution.

The key to understanding Lincoln’s first year is his unwavering focus on restoring the Union. Pursuit of this goal raised a number of questions. Could Lincoln prevent more states from seceding? Could he unite Republicans and Democrats, including residents of loyal slaveholding states, in a military effort to bring the Deep South back into the national fold? Could he negotiate a course relating to emancipation that would satisfy both the radical and more conservative wings of the Republican Party, while at the same time not alienating Democrats and residents of the Border States? And would success in all these arenas result in a restored Union?

Although the 19th-Century meaning of Union has disappeared from our national historical memory, Lincoln knew most of his fellow citizens cherished what they considered an exceptional government bequeathed by the founders—a democratic republic that featured a popular voice in political decisions and the chance to rise economically. Alone among the nations of the western world, the United States—the Union—offered an almost universal white male franchise and allowed singular social and economic mobility. The new president, himself an example of how common men could rise in the American Union, identified what most people considered the twin pillars of American exceptionalism. What lay at stake in the war, he explained in December 1861, were “the first principle of popular government—the rights of the people” and protection of a system that blocked “any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer.”

Lincoln’s First Inaugural Address underscored the centrality of Union. It targeted different groups with varied appeals to their allegiance to the republic. “The Union of these States is perpetual,” the president insisted, much older than the Constitution and made more perfect by the work of the Philadelphia convention of 1787. “Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy,” Lincoln proclaimed, a violation of the sovereignty of a free people in a nation dependent upon acquiescence in majority rule. As a former Whig who remembered when that party had robust northern and southern wings, Lincoln mistakenly believed large numbers of white southerners possessed strong unionist sentiment. He reached out to this supposed pro-Union constituency, as well as to northern Democrats, promising he had “no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists” and affirming as well that he would uphold constitutional provisions regarding fugitive slaves—parts of his address that left abolitionists and some radicals within his own party deeply unhappy. He also sought to reassure northern unionists with a pledge “to hold, occupy, and possess the property and places belonging to the Government and to collect the duties and imposts.”

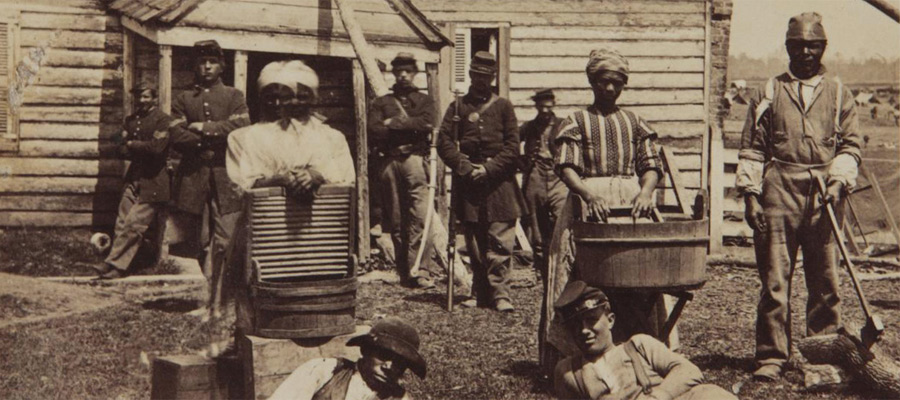

The Confederate $100 banknote showed slaves at work. In his first Inaugural Address, President Lincoln emphasized slavery’s role in the political fracturing of the nation.

Toward the end of his address, Lincoln emphasized slavery’s role in the political fracturing of the nation, sought to separate secessionists from unionists in the South, and engaged listeners with an eloquent plea for Union. “One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended,” he observed, “while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute.” Culpability for destroying the Union and possibly bringing on armed conflict lay entirely with secessionists. “In your hands, my dissatisfied fellow-countrymen,” stated the president clearly, “and not in mine, is the momentous issue of civil war. . . You can have no conflict without being yourselves the aggressors.” Then he offered a lyrical tribute to Union that pulled at shared memories of the revolutionary generation’s sacrifice: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battle-field, and patriot grave, to every living heart and hearthstone, all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

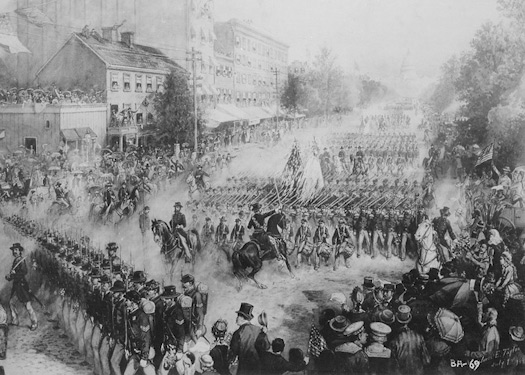

After the Confederates open fired on Fort Sumter, a federal fort in Charleston Harbor, President Lincoln moved to crush the Confederate rebellion.

Lincoln continued to stress Union throughout his initial year in office. When efforts to manage the volatile standoff at Fort Sumter failed in mid-April, he used George Washington’s precedent during the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794 to call forth 75,000 militiamen to crush the Confederate rebellion. “I appeal to all loyal citizens to favor, facilitate and aid this effort,” he wrote, “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuation of popular government.” Four states of the Upper South reacted to Lincoln’s call for volunteers by joining the breakaway slaveholding republic, prompting the president to comment that in Virginia, Tennessee, North Carolina, and Arkansas “the Union sentiment was nearly repressed, and silenced.” This evaluation overlooked the fact that solid majorities in all these states clearly supported secession rather than participation in a military effort to coerce the Deep South back into the Union.

With 11 states gone, Lincoln allocated a great deal of energy to keeping Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri—three of the four remaining loyal slaveholding states—in the Union, as well as to framing mushrooming demands for men and materiel in such a way as to keep northern Democrats on board with the war effort. In both endeavors, he consistently highlighted the importance of Union, as well as the necessity of taking an array of sometimes controversial actions to save it.

At the start of the Civil War, President Lincoln doubled the size of the regular army and navy and began enrolling thousands of federal volunteers.

On April 15, in the same message that called out the militia, Lincoln set July 4 as the date for the 37th Congress to meet in special session. The cumbersome election calendar occasioned this delay. Several states held congressional elections in the spring of odd-numbered years, which meant that all members would not be in place until June. Once the House and Senate convened, the president sent a message discussing his actions since taking office. He had instituted a naval blockade, commenced the enrollment of thousands of three-year federal volunteers, doubled the size of the regular army and navy, and authorized General-in-Chief Winfield Scott to suspend the writ of habeas corpus in parts of Maryland and elsewhere. All these presidential decisions prompted complaints, principally from Democrats but to a lesser degree from conservative Republicans, about excessive executive authority. Lincoln defended his actions as necessary and legal. Creation of the Confederacy had placed “an imperative duty upon the incoming Executive, to prevent, if possible, the consummation of such an attempt to destroy the Federal Union.” By firing on the federal garrison at Fort Sumter on April 12, averred the president, the rebels had “forced upon the country, the distinct issue: ‘Immediate dissolution, or blood.’”

Lincoln understood that Republicans could not restore the Union without help from the 45 percent of the loyal citizenry who called themselves Democrats. He knew as well that only a war in the name of Union could galvanize Republicans and Democrats to fill the ranks of large national armies, pay an array of federal taxes, and accept other burdens related to the conflict. To promote a unified war effort, Lincoln walked a delicate line regarding emancipation. Most Democrats expressed vociferous opposition to the idea of fighting a war to end slavery, and a large majority of unionists in the loyal slaveholding states especially balked at risking white lives to achieve black freedom. Within the Republican Party, some conservatives echoed Democrats while members of the radical wing pushed early and often for the addition of emancipation to Union as a goal for the U.S. war effort. Tensions between the president and Democrats and between him and the radicals grew during 1861 and into the first three months of 1862.

Abolitionists and radicals saw the war as a political upheaval that could open the door to ending slavery. Many of them hoped to tie prospects for Union victory to emancipation, declaring the latter necessary to defeat the rebels. They would have preferred a grand moral crusade but understood how few white citizens would embrace such an idea. The longer and bloodier the conflict, they reasoned, the better the chances for emancipation. Radical senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts made this point in a letter to abolitionist Wendell Phillips following the Union disaster on July 21, 1861, at First Bull Run. “The battle & defeat have done much for the slave,” Sumner wrote on August 3, “... I told the Presdt that our defeat was the worst event & the best event in our history; the worst, as it was the greatest present calamity & shame,—the best, as it made the extinction of Slavery inevitable.”

Lincoln knew such sentiments would outrage those who sought restoration of the Union as quickly and with as little bloodshed as possible. During his first year, almost 750,000 citizen-soldiers donned blue uniforms, news from battlefields such as Bull Run, Wilson’s Creek, Ball’s Bluff, and Forts Henry and Donelson buffeted Washington and the northern home front (all but the forts marked Union defeats), and officers such as George B. McClellan, Henry W. Halleck, and U.S. Grant rose in prominence. The attention of the populace, and of the president, typically centered on operations conducted by U.S. forces.

As a private citizen, Lincoln would have joined abolitionists such as Wendell Phillips in cheering for slavery’s demise, but as president, he had to balance competing political interests.

Against that compelling military backdrop, Lincoln wrestled with the question of emancipation. As a private citizen, he would have joined Sumner and Phillips in cheering for slavery’s earliest demise. But as president he had to balance competing political interests that came into play as the United States created and supplied armies on an unprecedented scale and dealt with the consequences of battles across a vast strategic landscape. On August 6, 1861, he reluctantly signed the First Confiscation Act, which freed slaves directly involved with supporting the Confederate military resistance, but three weeks later instructed Major General John C. Frémont to rescind an order liberating all slaves belonging to pro-Confederate residents in Missouri. Frémont’s action, counseled the president, “will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us—perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky.” The general, added the president, should bring his order into conformity with the more limited reach of the First Confiscation Act.

In his first annual message to Congress on December 3, 1861, Lincoln again sought to reassure all friends of the Union. “The Union must be preserved,” he stated, and all “indispensable means must be employed.” But he set strict limits, arguing, with emancipation at least partly in mind, “We should not be in haste to determine that radical and extreme measures, which may reach the loyal as well as the disloyal, are indispensable.” He did not want the conflict to “degenerate into a violent and remorseless revolutionary struggle” and “therefore, in every case, thought it proper to keep the integrity of the Union prominent as the primary object of the contest on our part, leaving all questions which are not of vital military importance to the more deliberate action of the legislature.” If another congressional law relating to confiscating rebels’ slaves were to be proposed, concluded Lincoln, “its propriety will be duly considered.” A flurry of congressional actions relating to slavery would reach Lincoln’s desk during the next several months—ending slavery in the District of Columbia and the federal territories, vastly expanding the reach of the First Confiscation Act with a Second Confiscation Act, and addressing the status of black refugees reaching Union military lines—but none arrived before the first anniversary of his inauguration.

Lincoln supported voluntary colonization for freed slaves, likely stemming from an honest belief that African Americans could not achieve true equality in the United States.

In line with his desire to court Democrats and border state residents, Lincoln insisted that emancipation in loyal states must follow constitutional guidelines. He sought to persuade the border states to adopt individual plans that would yield gradual emancipation with compensation for owners. The newly liberated black people, he thought, and perhaps those already free in the northern states, should be urged to colonize, as he put it in his December message to Congress, “at some place or places in a climate congenial to them.” Lincoln urged Congress to vote money to help compensate owners who lost slaves and to defray the cost of colonization. His support for voluntary colonization, which continued late into the war (he never recommended forced emigration), likely stemmed from an honest belief that African Americans stood little chance of achieving anything approaching true equality in the mid-19th Century United States. But it also represented an attempt to gain support from Democrats and others who detested the idea of integrating large numbers of free black laborers and their families into the nation’s social and economic structures. Most black Americans, abolitionists, and many Radical Republicans stridently opposed Lincoln’s thinking about colonization, while the border states rebuffed his recommendation that they draw up plans for emancipation.

Lincoln closed his first year in office as an executive who had taken bold actions to combat a vast rebel insurgency. He realized that only a war unequivocally waged to save the Union would inspire widespread support among the loyal citizenry of the United States. Assailed by Democrats on a range of issues, he also endured sustained criticism from Radical Republicans for his handling of emancipation. On March 6, 1862, two days past the first anniversary of his inauguration, he sent a message to Congress. If rebel intransigence continued, Lincoln remarked, “the war must also continue; and it is impossible to foresee all the incidents, which may attend and all the ruin which may follow.” Neither he nor anyone else could imagine what was to come. The massive bloodletting at Shiloh, just one month hence, would recalibrate the scale of military slaughter, after which three years of escalating political upheaval, profound swings in civilian morale, and a stark pivot toward more revolutionary outcomes more than once threatened a permanent sundering of the Union.