Upon taking office President George W. Bush quickly turned his attention to his domestic agenda—lowering taxes, education reform, and the implementation of a strategy of compassionate conservatism through faith-based initiatives. But he faced a real challenge: his foreign policy advisors were saying contradictory things.

“For the first time in decades,” commented Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in March 2001, “the country faces no strategic challenge.… We don’t have to wake up every morning thinking something terrible is going to happen.” But two months later, George Tenet, director of the CIA, warned Condoleezza Rice, Bush’s national security advisor, that “100 percent reliable information” suggested an impending “spectacular” terrorist attack against American or Israeli interests. “This is real.… We are going to get hit,” he told skeptics within the administration.

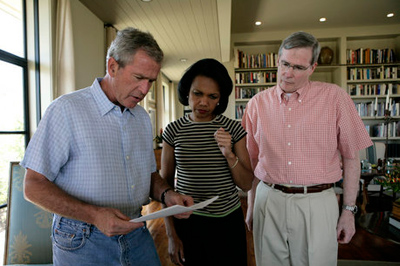

President George W. Bush assembled a foreign policy team that included (from left to right), National Security advisor Condoleezza Rice, Secretary of State Colin Powell, and Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld.

Nonetheless, in mid-July, when Rice asked State Department officials to begin drafting the administration’s national strategy statement, they slighted the terrorist threat, noted the absence of any global rivals, stressed America’s “unparalleled strength,” and heralded a “time of opportunity.” Rumsfeld was otherwise preoccupied. On September 10, before a large audience at the Pentagon, he declared: “The topic today is an adversary that poses a threat, a serious threat, to the security of the United States of America…[it] attempts to impose its demands across time zones, continents, oceans, and beyond.… It disrupts the defense of the United States and places the lives of men and women in uniform at risk.” That adversary, Rumsfeld pronounced, was the “Pentagon bureaucracy.”

These vignettes reflect the discord and the lack of urgency during the Bush administration’s first few months. While ambiguity and uncertainty are not uncommon in newly installed presidencies, the first year of the Bush administration illustrates how important it is for a president to impose his own imprimatur on the nation’s foreign policy goals and priorities, and how essential it is to bring together a team of advisors who embrace those goals, trust one another, and share confidence in their own decision-making machinery. These advisors must also think strategically, rigorously assessing and ranking threats, delineating priorities, and linking tactics and goals.

Bush’s presidential campaign got off to a good start in 1999. A Texas governor and former businessman, Bush did not have much knowledge of foreign policy or national security, and he knew it. So he invited Condoleezza Rice, a former Russia expert on his father’s national security staff, to tutor him and to put together a team to formulate overall policy direction. The group, known as the Vulcans, included Paul Wolfowitz, Richard Armitage, Robert Zoellick, and Dov Zakheim, among others.

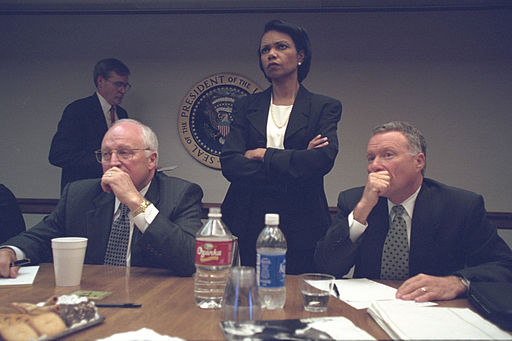

George W. Bush’s foreign policy was formulated by a team of advisors including Vice President Dick Cheney and National Security advisor Condi Rice.

The team fashioned several excellent speeches for candidate Bush, and prepped him for his debates with Al Gore, the Democratic candidate. In his campaign speeches and debates, Bush emphasized the importance of military strength yet wanted the United States to act with humility and empathy. The United States, Bush declared, must not withdraw, and must not drift. “America must be involved with the world,” he said. It must rebuild its military capabilities. But military action must not be “the answer to every difficult foreign policy situation”; it must not “substitute for strategy. American internationalism should not mean action without vision, activity without priority, and missions without end.” Bush stated his priorities clearly: Work with strong democratic allies in Europe and Asia; promote democracy in the Western Hemisphere; defend “America’s interests in the Persian Gulf and advance peace in the Middle East,” with a secure Israel; check the spread of weapons of mass destruction; and promote free trade.

Vice President Cheney (left) served as secretary of defense for Bush’s father.

To carry out this foreign policy, Bush appointed people of great experience and immense stature. His vice presidential running mate was Richard Cheney, a former chief of staff to President Gerald Ford and former secretary of defense; his secretary of state was General Colin Powell, a former national security advisor to Ronald Reagan and former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Donald Rumsfeld was his selection for secretary of defense, a former ambassador to NATO, secretary of defense under Gerald Ford, presidential envoy for Ronald Reagan, and chairman of a national advisory study on ballistic missile defense during the Bill Clinton years. Condi Rice, who was not only Bush’s foreign policy mentor but had become his trusted friend, was appointed national security advisor. Her task was to coordinate, not to operate; to reconcile divergent views, not to impose her own agenda. Bush prided himself on his managerial and leadership skills: pick exceptional people, stress team work, and delegate responsibility.

But the process did not cohere and a clear strategy did not emerge. The transition was delayed because of the controversy over the election’s outcome, and the deliberations of the Supreme Court. Appointments came slowly, then the exceedingly laborious confirmation process handicapped planning and complicated coordination.

From the outset, the principals did not agree and did not really trust one another. Bush did not appoint a secretary of defense he knew well, nor a secretary of state. And Rumsfeld and Powell did not hit it off; their staffs sniped at one another, as did those of the secretary of state and the vice president. The president mostly stayed aloof from these disputes.

As National Security advisor, Rice and her assistant, Stephen Hadley (right), tried to coordinate Bush’s foreign policy team but with little success.

Coordination was difficult, despite Rice’s efforts and those of her assistant, Steve Hadley. Vice President Cheney and his staff proceeded to play a key role in national security matters, yet Cheney mostly voiced his own views privately to the president and not to others. Meetings of deputies and principals were frustrating. Powell did not say much; Rumsfeld liked to ask questions and pose options rather than state his own clear preferences. Rice struggled to establish her authority, failed to garner the full respect of the principals and deputies, and futilely sought consensus when there was none. She knew the president was capable of making tough choices, yet cabinet secretaries and their staffs remonstrated against her reluctance to present the president with divergent options.

Frustration abounded and disarray ensued. For example, establishing better relations with Mexico was a presidential priority. Less than a month after taking office, the president visited the ranch of Vicente Fox, Mexico’s president. The aim was to highlight Mexico’s importance and America’s humility. But during the first press conference, everyone’s attention was distracted by news of an American attack on Iraqi air defenses close to Baghdad. The unplanned American action was precipitated by Iraqi efforts to challenge the no-fly zones imposed by U.S. air power. The news disrupted the meeting; it was a “disaster,” Condi Rice acknowledged. She blamed herself.

President Bush and President Fox of Mexico met early in Bush’s first year but their meeting was overshadowed by U.S. attacks in Iraq.

Less than two weeks later, Kim Dae-jung, the South Korean president, came to visit Washington. President Bush wanted to convey privately that his administration did not favor the South Korean’s conciliatory policy toward North Korea, an approach that the Clinton administration had broadly endorsed. Yet during the visit, Secretary of State Powell said that the United States would continue the approach of his predecessor. Bush was furious, and asked Rice to get Powell to issue a correction. Powell complied, but Rice recognized that “the public perception of Colin Powell being reined in by the White House lingered and festered.”

At almost the same time came a terrible flap over the Kyoto Protocol on climate. The president wrote a public letter to four Republican senators categorically announcing the administration’s opposition. Rice read a draft and knew it would alienate European allies. Wanting to modify the language, she went to the president and learned that Vice President Cheney was already delivering the letter to the Hill. She was “appalled,” she later wrote, that Cheney moved ahead without her assent, or that of the secretary of state. She knew it would sour relations and damage America’s reputation abroad; it did, as do most changes in policy that are not carefully rolled out. “We handled it badly,” Rice acknowledged.

Then came a real crisis with China, when an American espionage plane collided with Chinese aircraft and had to land on Hainan Island. A Chinese pilot was killed in the crash, and China’s government demanded an apology. Since the American plane was flying in international airspace when the incident occurred, defense officials dug in their heels while their counterparts at Foggy Bottom wanted to talk. The Chinese were “testing” us, Rumsfeld insisted. Bush deferred to Powell, and the crisis was resolved by smart diplomacy and mutual accommodation. Rice acknowledged that “this was not the way we’d hope to start off our relationship with Beijing.” But the unexpected always happens, and knowing one’s priorities is critical to successful policy.

More successful were relations with Russia. From the outset of the administration, Bush made clear that ballistic missile defense was a priority. To achieve it, the United States had to disentangle itself from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty of 1972. Although Russian president Vladimir Putin was opposed, Bush communicated this priority to him at their first meeting in June 2001 and successfully prepared the groundwork at home.

President George W. Bush had good relations with Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Yet all these matters paled in comparison to the indecision over what do with Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and how to deal with the threat posed by the Islamic terrorist group known as al-Qaeda, headquartered in Afghanistan and led by Osama bin Laden. Contrary to popular myth, Bush’s advisors had no plans for military action against Iraq. They wanted regime change, but their real focus was on how to handle the erosion of the sanctions regime and the protection of aircraft enforcing the no-fly zones. Deputies and principals met repeatedly to discuss options, with very few concrete results. “The effort to make the sanctions smarter was maddeningly slow,” conceded Rice in her memoir. The bickering and indecision infuriated Rumsfeld, although he posed options rather than offered solutions. Paul Wolfowitz, the deputy secretary of defense, wanted to topple Saddam, but offered no precise plan. Rumsfeld himself was far more interested in reforming the Pentagon than in transforming Iraq. Bush offered little leadership.

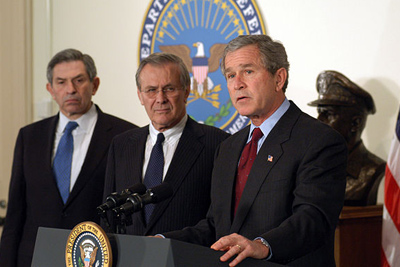

Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and President George W. Bush had differing opinions on how to handle Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and the threat of al-Qaeda.

Nor was there any clarity on the threat posed by al-Qaeda. Richard Clarke, the counterterrorism expert on the NSC staff, was held over from the Clinton administration, as was George Tenet, the director of the CIA. Both these men screamed about the threat posed by al-Qaeda. “The threat from terrorism is real, it is immediate, and it is evolving,” Tenet told the Senate Armed Services Committee in March 2001. The director of the Defense Intelligence Agency said the same thing: the immediate threat over the next 12–24 months “was a major terrorist attack against the United States either here or abroad.” Clarke protested to Rice and Hadley that they needed to move quickly, and Tenet pounded on the desk of his friend, Richard Armitage, the deputy secretary of state, and warned of an imminent attack. Yet Rice and Hadley felt that a regional strategy needed to be designed before directly tackling the al-Qaeda threat. They postponed meetings of deputies and principals until such a strategy was scripted, yet pushed ahead with the appropriate work. Papers were prepared and key meetings were scheduled for September.

President Bush was not indifferent to the terrorist threat. He asked for a presidential daily briefing on the topic that took place on August 6. But he did not dwell on the matter either before or after that briefing. He did not ask for subsequent meetings; did not convey any interest commensurate with the shrill warnings being conveyed by his CIA director and chief White House counterterrorism expert. These men carried little influence within the administration. They were Clinton holdovers in an administration steadfastly committed to changing direction from anything linked to Clinton. Moreover, Clarke was viewed as a self-promoting bureaucratic entrepreneur, inclining his colleagues to minimize his admonitions, especially when those warnings became more muted in the late summer of 2001. Homeland security, Rice believed, was not her domain: it was the FBI’s. Nor was there sufficient reason for her to be concerned with it, she thought.

George Tenet, director of the CIA, tried unsuccessfully to draw the administration’s attention to the threat of al-Qaeda.

Rice and Hadley wanted a regional strategy, including Afghanistan and Pakistan, to deal with al-Qaeda. Their colleagues in the vice president’s office, like Eric Edelman and Scooter Libby, felt that what the administration really needed was an overall global strategy, with a clear delineation of worldwide threats and a set of national goals and regional priorities. Yet the principals and deputies rarely, if ever, discussed overall strategy or priorities. The president and vice president continued to focus mainly on their domestic agenda.

In the summer of 2001 Rice asked the State Department policy planning staff to draft an overall strategy paper. Without so noting, the priorities were remarkably similar to those of the Bush 41 and Clinton administrations: promoting open trade and more freedom in the world. U.S. goals were to collaborate with America’s democratic allies; preserve America’s superior power; forge “realistic” relations with Russia and China; and alleviate poverty, disease, corruption, and tyranny in the world. The principal “impediments” to these goals were prospective disputes with democratic allies, anticipated renewal of great power competition, and endemic poverty and corruption in parts of Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The draft included a passing allusion to the threat of terrorism, but did not even mention al-Qaeda. U.S. interests were not clearly defined; means and ends were not reconciled; regional strategies were still to be designed.

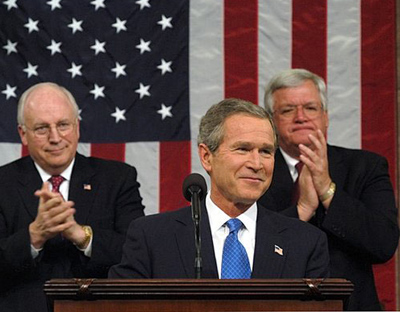

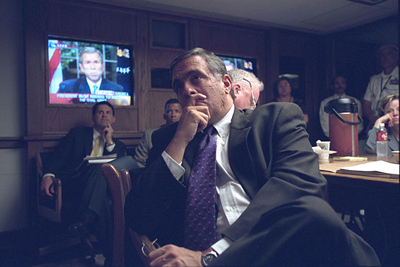

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, President Bush focused on national security policy and launched the global war on terrorism.

Incomplete, the overall strategy—regarded primarily as a bureaucratic exercise to comply with a legislative mandate—was not vetted among the principals nor discussed at NSC meetings. President Bush showed little interest in it. Nor did Secretary Powell; he preferred to react to ongoing challenges, and especially wanted to deal with Palestinian-Israeli strife. Rumsfeld focused on reforming the Pentagon, advocating the case for ballistic missile defense, fighting the entrenched Pentagon bureaucracy, and circumventing many top military officers, several of whom detested him. Cheney was deeply interested in security, intelligence, and energy matters, but he shared his thoughts only with the president. Tenet and Clarke were obsessed with the terrorist threat, but the Joint Chiefs showed no special interest in such matters.

In these initial months, notwithstanding the president’s hopes, there was much bickering, poor teamwork, and incessant badmouthing. The president did not pay much attention to these matters, engaging selectively on some issues but providing little overall direction. While he effectively led meetings, he did not demand the teamwork and accountability he prized. Nor did he underscore the authority that Rice needed to do her work successfully. He made little effort to discuss overall strategy, shape a consensus about priorities, and think seriously about means and ends. He did not grapple with the impact of domestic initiatives, such as tax cuts, on national security goals, such as military transformation and rearmament. Policy was not shaped by a tough assessment of threats; warnings by Clintonian holdovers were minimized.

After September 11, President Bush focused the initial U.S. response on Afghanistan.

After 9/11, the president did take command, riveted his attention on national security policy, and launched the global war on terrorism. His priority was set: destroy terrorists with a global reach and the regimes that accorded them safe haven. The initial mission, he insisted, should be Afghanistan, not Iraq. But the Defense Department and the CIA continued to dispute tactics. Frustrated, on October 10, 2001, Rumsfeld lashed out again at his subordinates: “We have tens of thousands of dedicated, talented, creative people.… But something is fundamentally wrong in the department.… I am seeing next to nothing that is thoughtful, creative, or actionable.” Nonetheless, soon thereafter, the Taliban were defeated by creative actions of CIA operatives, U.S. air power, and the Northern Alliance inside Afghanistan.

Condi Rice hired Philip Zelikow to rewrite the Bush administration’s national security strategy statement although the document was not fully vetted within the administration.

The administration embraced victory with enormous satisfaction. But victory was self-defeating because it nurtured hubris and reduced incentives to reflect on a decision-making process that remained flawed. Nor did it lead to a clear strategic overview about subsequent priorities and actions, other than an inchoate consensus that the greatest threat to U.S. security was the nexus of state actors, terrorists, and weapons of mass destruction. In fact, Rice hired a trusted nongovernmental confidante, Philip Zelikow, to rework the administration’s national security strategy statement. The paper, carefully perused by the president, was not vetted thoroughly through the various agencies, nor discussed among the principals or deputies. Subsequently, there was no meeting to discuss the pros and cons of waging an invasion of Iraq, and the planning for the posthostilities regime in Iraq was wracked with confusion, indecision, and overlapping chains of command between the Coalition Provisional Authority, the Defense Department, the State Department, the national security advisor, and the White House.

What is there to learn? National security decision-making requires strategic thinking that integrates threat perception, reconciles domestic and foreign policy priorities, and links means and ends. It requires teamwork among decision makers, clear lines of authority, a respected and tough-minded national security advisor, and an understood process among the decision-makers themselves. Most of all, it requires a strong, focused, and inquisitive president, inclined to assess and rank threats, think strategically, discuss overall goals and tactics, and articulate priorities. Although the president should delegate responsibility, the commander in chief must also be attuned to and ready to resolve differences among advisors. When priorities are agreed upon, as was the case with ballistic missile defense, effective policy may ensue. But precipitous changes without careful deliberation and systematic rollout will be harmful, as was the case with the president’s unilateral renunciation of the Kyoto initiative on climate or his desire to change course regarding Korea.

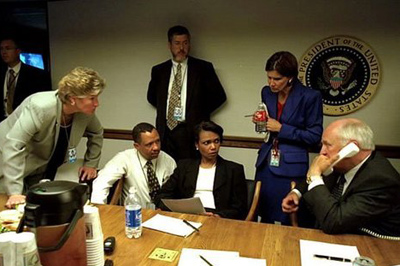

After the September 11th attacks, Vice President Cheney (on phone) and members of the Bush administration gathered in the Presidential Emergency Operations Center.

Bush’s first year shows how daunting can be the challenges of national security even for a president who has chosen advisors of great stature and vast experience, as did our 43rd president. Of course, presidents do learn and recalibrate. Even better if they think through these matters prior to assuming the great responsibilities that await them.