The Miller Center hosted a First Year event, “A new dialogue on race in America.”

There are, now, two profound paradoxes at the heart of American race relations. The first is very evident to anyone who keeps abreast of the news: It is the fact that in the final year of the nation’s first black president, there was growing pessimism and outrage about race in the nation. This is reflected in the Black Lives Matter movement; demonstrations against racism on campuses; outrage over the repeated killing of black youth by police officers; and a general sense that racial progress has stalled and may even be getting worse. A recent Kaiser Foundation study reports that almost two-thirds of the public (64 percent) say racial tensions have increased in the country over the past decade.

What happened to the optimism and triumphalism about American democracy and racial progress that greeted the historic election of President Barack Obama in 2008? How, of all times since the 1960s, could the nation now find itself in anguished discussions, with popular works such as Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me little more than cries of hopelessness about its racial failures?

Although President Barack Obama became the nation's first black president, there was growing pessimism and outrage about race during his administration.

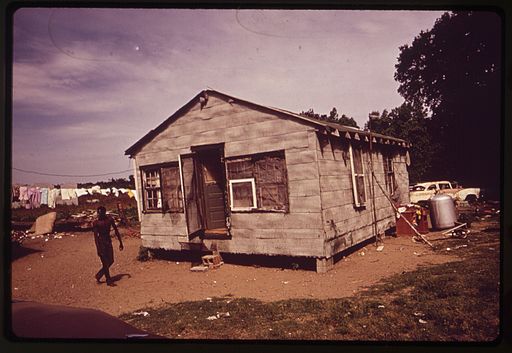

This first paradox—call it the Obama Paradox—must be seen in terms of a broader and deeper contradiction. After centuries of exclusion, black Americans have been almost wholly accepted into the public sphere of American life and are central to the nation’s definition of itself as a political and social community. And yet, at the same time, black Americans remain extraordinarily excluded from most regions of the nation’s private sphere: They are as segregated as ever, have remarkably few intimate friendships with non-blacks, and are the most endogamous group in the nation. This apartness from the nation’s private sphere—two eminent sociologists have labeled it “American apartheid”—has worsened even as their public integration has greatly increased. A black man was twice elected to the presidency; blacks have occupied the nation’s major public offices: senators, governors, secretary of state, attorneys general, the chairmanship of the Joint Chief of Staff; and they are a major presence at all levels of the nation’s cultural life. And yet it is not inaccurate to say that at the private level they are still a largely excluded group, the great majority living in hypersegregated neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, misery, and violence, or else in picket-fenced middle-class communities that are best described as gilded racial ghettos.

First Year Video: Presidential Problems: Race And The Crisis of Justice

One striking expression of the view of blacks as outsiders among a significant segment of the population was the insistent belief that the black president of the nation was not born in America, a foreigner who had stolen “our nation” which “we want back.”

Blacks in the United States have struggled with persistent poverty as racism and segregation have limited their opportunities.

The other side of our paradox is the persisting poverty and apartness of most nonelite blacks from the nation’s private life. There was moderate absolute growth in the black median household income between the 1960s and present, but when we compare income change with that of white Americans we find that the gap has remained the same. In 1967, black median household income was 65.5 percent of the median white household income; in 2013 it was exactly the same. As is now well known, the staggering growth in inequality negatively affects all but the wealthiest Americans, but the black poor have suffered disproportionately. The poverty rate for blacks, having declined during the Clinton years from 32.9 percent in 1992 to 21.2 percent in 2000 (the lowest on record), climbed to 24.5 percent in 2007 and now stands at 27.4 percent. compared with 9.9 percent for whites. Early childhood poverty is now recognized as a reliable predictor of later poverty and social maladjustment, so it is alarming that 46 percent of black children under age 6 are living in poverty. The top-down nature of the economic gains is most strikingly reflected in the fact that inequality within the black group is substantially greater than it is among whites and the nation at large. Among blacks, the mean household income of the top fifth is 20 times that of the poorest fifth, compared with a multiple of 12 in the nation at large.

In light of all these profound social contradictions, what should our newly inaugurated president do?

On February 21, 2017, President Donald Trump spoke at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In 2014, President Obama established the Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which recommended greater transparency, community policing, and an end to racial profiling.

Steps such as the ones outlined here would represent crucial movement toward final completion of the thwarted black struggle for equality. For most of the 20th Century, that effort focused mainly on their exclusion from the public sphere of politics, law, work, and popular culture, or their discrimination within those few corners of the economy where they were tolerated. The civil rights movement marked the triumph of these efforts. And it was, by any reckoning, a revolution. Within less than a generation, the entire institutional infrastructure of Jim Crow was dismantled; the legal system came to support blacks and, in recognizing their equal rights, created a “rights revolution” that had enormous implications for other major disadvantaged groups, especially women, Hispanics, and gays. Accompanying these changes was a fundamental liberalization in the attitudes of the vast majority of whites toward blacks.

The Nurse-Family Partnership program has been shown to be effective for disadvantaged mothers and their children.

The movement, however, was in most respects a top-down revolution, one that largely benefited the middle and upper classes of whites and blacks alike. In this regard it made the American class system unique among the white majority societies of the world. No other diverse society, especially those with black minorities, comes close to America in the degree of integration of its elite, especially its elite public sphere.

This fragile economic base—along with persisting, though declining, labor market discrimination; residential and marital isolation; a reversal in educational attainment; as well as internal cultural problems persisting from slavery but reinforced by modern circumstances—accounts for a second stunning recent development. This is the finding that there has been massive intergenerational downward mobility from the black middle class. A recent Pew study reports that “a majority of black children of middle-income parents fall below their parents in income and economic status,” and fully half fall to the very bottom of the income ladder!

The paradox of public inclusion and persisting, indeed increasing, private separation is most glaringly revealed in the persistence of large-scale racial residential segregation in America. Segregation levels vary by region in quite unexpected ways, compounding the paradox. They are highest in precisely those regions of the country where blacks have achieved the highest levels of public integration: the metropolitan regions of the Northeast and Midwest. New York, the liberal heartland of America where blacks have, arguably, achieved the strongest presence and influence in public life, ranks near the bottom of the nation’s metropolitan areas in levels of residential integration.

The cast of Hamilton sings at the White House. Hamilton, the most successful show on Broadway, is a hip-hop musical.

Nowhere is the paradox of public inclusion and private separation more starkly found than in the present situation of black American youth, especially poor males. On the one hand, they are the most segregated segment of the nation’s population and face the most formidable set of socioeconomic problems. They have the highest rates of dropping out and delinquency in the nation. Although the great majority are law abiding, and homicide rates are at a 51-year low nationwide, violence has remained endemic among a disconnected 20 percent of these youth, with recent surges in Chicago and a few other cities creating problems for all. Delinquency, combined with draconian laws and an unfair justice system that targets all black youth, rather than the 20 percent who are disconnected, has resulted in a horrendous incarceration rate, in which blacks constitute nearly a half of this country’s 2 million prisoners. Those not incarcerated face unemployment rates of over 20 percent among those still seeking work. And yet this same group is the creator of a powerfully vibrant popular culture, one that has had an outsized impact on the broader culture of America, and is today perhaps the most potent force in the globalization of American popular influence. White American youth avidly consume the hip-hop cultural productions of black ghetto youth—their music, fashion, poetry, dance, lifestyle, and language—and whites of all classes and age groups idolize their sports heroes. The most successful show on Broadway, Hamilton, is a hip-hop musical.

How do we explain this paradoxical state of racial affairs?

The negative reaction of whites against the gains of blacks can only be understood in light of the surprising but well-documented fact that one major achievement of the civil rights revolution was a genuine liberalization in the racial attitudes of the great majority of whites. From a situation in the early 1940s, when most whites considered blacks racially inferior and approved of laws prohibiting intermarriage and forbidding the sale of homes to blacks, white American attitudes have evolved to the point where today the great majority—approximately 80 percent—claim to hold genuinely liberal views regarding racial equality. How then do we explain the resistance to policies aimed at helping blacks, and just as importantly, how do we explain the fact that so many blacks—over 50 percent according to a recent Kaiser Foundation study—report experiencing racial discrimination and avoidance in their daily encounters with whites?

One explanation is what Harvard Social Science Prof. Lawrence Bobo calls laissez-faire racism. The fact is that whites, while committed to the principles of racial equality and integration, nonetheless resist supporting policies that benefit blacks if they are perceived as harming their own interests or group position. The classic examples of this are hostility to affirmative action, school busing, and changing zoning laws to facilitate the desegregation of the society.

Another explanation is what I call “the 20 percent conundrum.” While the great majority of whites may genuinely claim to have liberal racial views, surveys and natural experiments indicate that a stubborn 20 percent of whites remain outright racists in their stereotyping of blacks and belief in their racial or cultural inferiority. We saw the extreme wing of this group on display in the violent rhetoric that was unleashed in the recent election season. The total white population, including Hispanic whites, amounts to 246.6 million, or 77 percent of the total U.S. population, while blacks, those who identify as mixed, and black-identified Latinos amount to 42 million, or 14 percent of the total. What this means is that for every black American there is still more than one outright racist. To complicate matters, a disproportionate number of this racist minority of whites are likely to be the very ones who encounter blacks in their daily lives and, worse, are likely to be in positions of institutionalized power, such as police officers, security guards, and small employers. Hence the conundrum wherein the great majority of whites can genuinely claim that they and their friends are not racists in the traditional sense (institutional racism aside) while the great majority of blacks can genuinely experience racist aggression in their daily lives.

So far, I have emphasized the exogenous factors in black-white relations, especially those springing from personal and institutional racism. I want to turn attention briefly to those endogenous factors that partly account for the persisting plight of blacks but that also spill over into black-white relations, especially in regard to white perceptions of blacks.

The most important of these is the growing number of children being born in and raised by single, usually female, parents—now over 70 percent. Sociologists have thoroughly demonstrated the deleterious consequences of single parenting. They include a high probability of such children being poor, their much greater risk of remaining poor as adults, of becoming single parents themselves, and of falling into delinquency and violence.

The high rate of violence within black communities has been a problem in Chicago, Illinois. Protestors in Chicago march for a more peaceful city.

Somewhat related to this is another major internal problem: the high rate of violence within black communities. Again, this is in part a function of poverty, poor schools, unemployment, overconcentration, and a chemically toxic environment. However, the street culture of thuggery, individual and gang violence, and engagement in the underground economy of illegal drugs cannot be wholly explained in terms of disadvantaged circumstances. Black communities have long been plagued by violence, going back to the 19th Century, as W. E. B. Du Bois documented in his sociological works near the end of the 1800s. Violence is in part the persistence of modes of responses to the violence of slavery and Jim Crow and to the problems of being brought up in single-parent families without the resources or the time to nurture and socialize children, especially boys.

Noting these internal sources of economic and social insecurity is not necessarily to blame the victim, as is often claimed, nor to support the racist view that blacks are culturally inferior. Contrary to right-wing views that the state can and should do nothing to help heal these problems, the fact that they are the historic result of state-sponsored slavery and institutionalized racial exploitation dictates the moral imperative that the American state do all in its powers to alleviate the worst effects of these internal problems, which are in good part the lingering effects of slavery and its aftermath, but now reinforced by economic inequality.