The Miller Center hosted a First Year event, “A new dialogue on race in America.”

President Barack Obama took important strides over two terms toward a more inclusive society, urging us to rethink the prevailing strategies of urban social programs that treat “entire neighborhoods as little more than danger zones where we just surround them.” But the nation still has a long way to go.

The real—and perhaps the only—long-term solution to the dynamic Obama identified requires a major infusion of resources and policies that would empower residents in overpoliced communities to transform their own conditions on their own terms. It is the responsibility of the new president, in the earliest phase of his administration, to encourage new conversations about racism, to foster a more meaningful role for the most isolated citizens in shaping the domestic programs that directly affect their everyday lives, and to enact legislation providing the necessary funding and support for those initiatives.

First Year Video: Presidential Problems: Race And The Crisis of Justice

As policy makers, scholars, and the public are increasingly recognizing, a transformation of the fundamental logics of our domestic policies will be necessary to fully realize the democratic principles of this nation’s founding and to evolve from our current mass incarceration society in which the criminal justice system perpetuates racism and poverty.

Fortunately, the new president has taken office at a time when the question of how to move beyond historical and institutional racism is entering national conversations in a way we have not witnessed since the civil rights era. Coverage of police misconduct and brutality against black and Latino citizens can be found in the pages of major news outlets on a daily basis. Social movements for equal rights continue to gain momentum—millions of citizens took to the streets the day after Donald Trump’s inauguration in protest. And across political and ideological lines, many Americans are outraged by the brutal social and economic costs of maintaining the largest prison system on the planet.

We have not seen this level of commitment to egalitarian values since the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, when federal policy makers made combating racial discrimination and poverty a central goal of domestic policy. Yet even as John F. Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson established critical reforms that are still with us, such as the Head Start prekindergarten program, the vocational training and remedial education measures of the New Frontier and Great Society focused on changing the behavior of “antisocial” and “alienated” citizens who suffered from racial discrimination to inspire them to become more “productive” citizens. Unfortunately, the strategy of fighting the effects of inequality rather than its root causes failed to address the larger structural issues of failing school systems, mass unemployment, and substandard housing.

The administrations of John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson used federal policy to combat racial discrimination and poverty.

To capitalize on the current momentum in our national discourse, the new president must not fall into the logical trap that ultimately undermined the work of Kennedy and Johnson. The social programs of the 1960s placed the onus on low-income African Americans themselves to “fix” the problem of racism, a strategy that left the institutions that have effectively reproduced inequality since emancipation largely unaffected. In practice, the equal opportunity programs of the War on Poverty translated to “helping the disadvantaged help himself,” in the words of Lyndon Johnson’s attorney general, Ramsey Clark. Thus, instead of identifying larger historical and systemic patterns or working to combat the destructive pathology of white American racism, policy makers expected black citizens to cope with their own experiences of marginalization.

The tendency on the part of lawmakers and officials to remove themselves from accountability for limited housing options and job prospects, as well as violence in low-income communities, and to blame black citizens themselves for the consequences of institutional racism is alive and well today. Take, for example, former President Bill Clinton’s response to Black Lives Matter activists who challenged him in April 2016, on the role of his administration in exacerbating the criminalization and incarceration of black youth. “I don’t know how you would characterize the gang leaders who got 13-year-old kids hopped up on crack and sent them out to the street to murder other African American children. Maybe you thought they were good citizens,” Bill Clinton said at a campaign rally for his wife. “You are defending the people who kill the lives you say matter.”

White Americans need to take responsibility for the ways in which policies have sustained the systematic exclusion and exploitation of black Americans.

Until former President Clinton and others are willing to confront the impact of white privilege, and the ways in which the policies they created sustained the systematic exclusion, exploitation, and extraction from citizens of color, the “blame the victim” approach to solving the racial problems that have marred this country since its founding will remain. In effect, Clinton suggested that the central issue was not his Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994 that exacerbated mass incarceration and criminal justice disparities by introducing 100,000 police officers on the streets of targeted urban areas, expanding mandatory minimum sentences, and incentivizing prison construction, among other draconian provisions. Instead, Clinton ultimately blamed the harm citizens living in already vulnerable neighborhoods inflict on one another for socioeconomic problems and racial profiling.

As a first step in moving toward a more equitable and just nation, we must revisit the principles of community representation and grassroots empowerment that guided the early development of Great Society programs.

Congress enshrined its commitment to fostering community involvement as “maximum feasible participation” in the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964—the inaugural legislation of the War on Poverty. Based on the Saul Alinsky method of organizing, the idea of maximum feasible participation emphasized that only the widespread participation of local people, working with local agencies supported by the federal government, could change unequal circumstances. As officials in the Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) saw it, maximum feasible participation meant that the federal government had a responsibility to “assist the poor in developing autonomous and self-managed organizations which are competent to exert political influence on behalf of their own self-interest.” The Johnson administration and Congress charged the OEO with ending the systematic exclusion of poor people from urban social welfare programs and assisting them in developing their own solutions to cure and prevent the symptoms of poverty. Unlike the “blame the victim” approach later adopted by Clinton and others, during the 1960s national policy makers recognized the devastating impact of historical discrimination and sought to use national resources to end racial inequality by empowering marginalized communities.

For activists, organizers, and residents of segregated low-income neighborhoods throughout the United States, maximum feasible participation opened the door for radical approaches to disrupting existing racial hierarchies and exercising the claims to self-determination demanded by mainstream civil rights leaders in the mid-1960s. For instance, with support from the OEO, the Mobilization for Youth program in Manhattan’s Lower East Side confronted public school administrators, the New York City Department of Welfare, and the police department. And in Chicago, the Woodlawn Organization received a $1 million development grant to work with youth gang members. It was the first—and only—time that grassroots organizations received direct federal funding to address social problems in their communities on their own terms.

The efforts of the program in New York, Chicago, and other major American cities changed the lives of many of the most marginalized and isolated citizens in important ways. In Syracuse, the Community Development Corporation sought to assist low-income residents in improving their immediate conditions. Federal funding enabled various neighborhood organizations to demand lower rents from unresponsive slum landlords so that parents had enough disposable income to adequately feed themselves and their children. Protests at city hall fostered critical changes in public housing eviction policies to prevent needy families from sleeping on the streets. Sit-ins eventually led to the establishment of public recreational facilities, providing children with places to play after school and on weekends. And calls for proper garbage disposal led to a more humane environment in deprived neighborhoods overall.

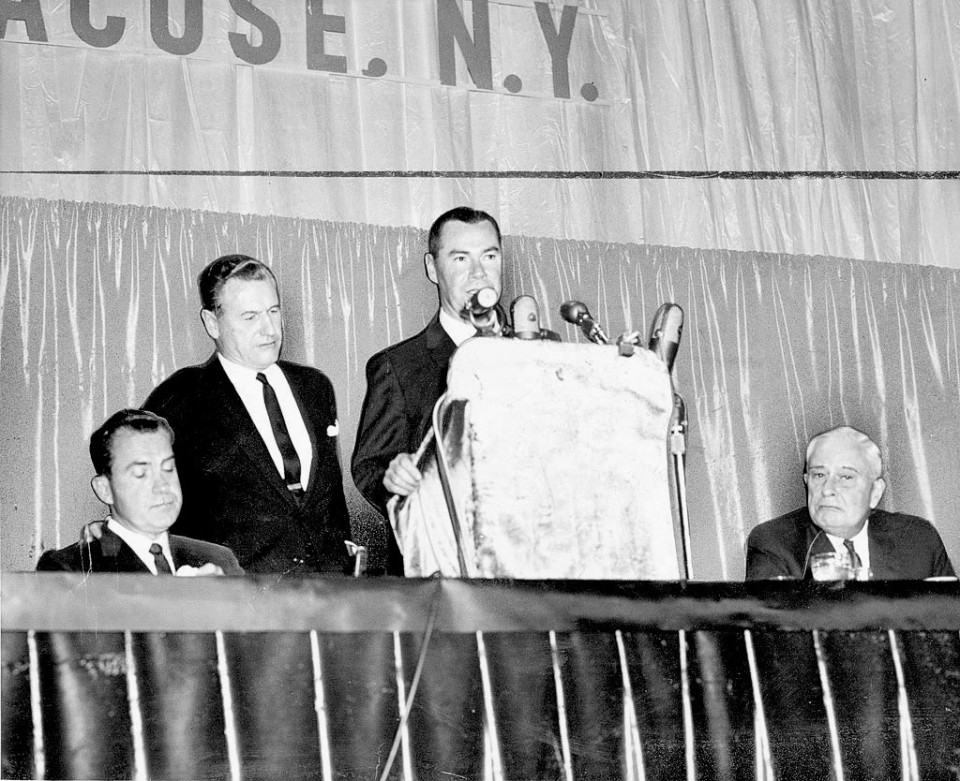

The tragedy of the Great Society—and, arguably, every other domestic social program of the 20th century—is that maximum feasible participation was never given a chance to work. The “blame the victim” approach to urban policy quickly overtook more transformative notions of liberal reform. Although the principle of maximum feasible participation did not cause much debate in Congress initially, it created power struggles over the administration and control of the War on Poverty. The approach also tested the Johnson Administration’s commitment to its own rhetoric about equal opportunity. With federal funds supporting campaigns against mayoral administrations and protests against local police departments, municipal officials bristled. Syracuse Mayor William Walsh asserted that maximum feasible participation was “fostering class struggle.” Congressional Republicans worried that federal funds would be used to build radical bases in low-income areas, fueling a major voter registration drive for the Democratic Party.

Although Syracuse, New York, implemented community programs to help those in need, Mayor William Walsh became a critic of those efforts.

As criticism of maximum feasible participation mounted among local officials like Mayor Walsh, who saw early Great Society programs as working against their self-interest, the possibility that the War on Poverty would lead to fundamental social transformations brought about by citizens themselves diminished. Promising initiatives that had been designed by grassroots organizations and that received federal funding directly during the first year of the War on Poverty were increasingly required to include public officials and municipal authorities in top-level positions.

What might the United States look like today had federal policy makers mobilized behind the principle of maximum feasible participation that steered the early programs of the War on Poverty with the same level and length of commitment as they gave to the War on Crime Johnson declared in March 1965? Before community action programs were given a chance to work on a wider level and for entire communities rather than individuals, federal policy makers decided to defund them and switch course. Lawmakers at all levels of government instead chose to invest in and support the growth of police forces, court systems, and prisons after Johnson launched his national crime control program.

Since the 1970s and 1980s, aggressive policing practices and mass incarceration have become the foremost civil rights issues of our time.

Thereafter, law enforcement officials took on a more prominent role in urban life and in social services in low-income neighborhoods as the federal government disinvested from equal opportunity, education, and other social welfare provisions during the Nixon administration and beyond. Stemming from the punitive shift in urban social programs during the 1970s, over the course of Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs, law enforcement officers came to provide the primary (and in some areas the only) public social services to residents. Aggressive policing practices and mass incarceration have become the foremost civil rights issues of our time as a result of this misguided policy path and the strategies policy makers have embraced for the past half century.

In July 2015, President Barack Obama addressed the NAACP convention and stated, "Justice is not only the absence of oppression, it is the presence of opportunity."

Yet the tide began to shift back toward a more progressive direction in the last years of Obama’s presidency. During his speech at the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) convention in July 2015, Obama indicated that for the remainder of his time in office, his administration would seek to reorient domestic policies toward social justice priorities rather than punitive ones. “Justice is not only the absence of oppression, it is the presence of opportunity,” Obama said, noting that a black man born in 1990 has a 50 percent chance of being employed today and is far more likely to spend part of his life behind bars than his white and Latino counterparts. The president went on to observe that the decision to spend $80 billion dollars a year on incarcerating citizens rather than allocating those resources to ensure that all American children can receive a preschool education is “not just a police problem; that’s a societal problem.” Picking up Obama’s cues, and under pressure from critical portions of her constituency, presidential hopeful Hillary Clinton pledged to make ending inequality “the mission” of her presidency. And when asked about the prospects for black youth in Harlem, Donald Trump recognized the need to create jobs—“You have to create the kind of economy where people can go out and work”—even as he exploited the deep racial divisions in America to mobilize potential voters.

The conversations and protest movements of the past several years will continue to put pressure on the new administration. It is critical that the president respond in a way that helps all Americans understand that policies benefiting black Americans, Native Americans, and other racially marginalized groups do not come at the expense of low-income or affluent white Americans. Dismantling structural barriers to socioeconomic opportunities for any disadvantaged group benefits all of American society.

This means that merely continuing Obama’s expanded late-administration discourse on race will not be enough. In terms of criminal justice reform, the new president must make clear that mass incarceration will no longer be the American status quo, and that he intends to move well beyond Obama’s work in this area. Laudably, Obama released a record number of 1,715 federal prisoners convicted on drug-related offenses during his administration. Yet if all drug offenders were released today, the United States would still be home to the largest prison system on the planet.

The new president must focus on programs that allow the people living in the affected communities to work together with organizations such as the police to overcome racism and inequality.

Thus our new national leader must articulate a vision of reform that includes, but goes well beyond, simply ending the War on Drugs, setting free those imprisoned for nonviolent offenses, and offering reentry programs in the failed mold of so many Great Society initiatives. In addition to traditional job training and remedial education programs, the formerly incarcerated need concrete routes to actual and stable employment. This will require significant job creation programs, access to secondary education within prisons, and an end to restrictions preventing incarcerated citizens from receiving federally funded scholarships for college. Finally, lifting restrictions on access to public services for those with criminal records will begin to reverse the ongoing criminalization of social welfare programs and poor citizens.

Now is the time, and the public and political support exists, for the new president to lead a transition from a mass incarceration nation that disproportionately ensnares black and Latino citizens toward a more complete and vibrant democracy. Instead of embracing the misguided politics of “law and order,” he can begin by looking back to the unrealized promises of the Great Society. Returning to maximum feasible participation as a guiding domestic policy principle will open an opportunity to confront finally the persistence of racism and inequality in America. For if we are to achieve lasting and meaningful change, low-income citizens—especially those who are deprived of access to clean water, adequate food, sanitation facilities, and basic public services—must be entrusted to lead the effort to rebuild their communities and to be fully integrated into public institutions at all levels.

A vision of this path forward can and must be enunciated early in the first year of the Trump administration. As the University of Virginia’s founder, Thomas Jefferson, reminds us: “The care of human life and happiness, and not their destruction, is the first and only object of good government.”