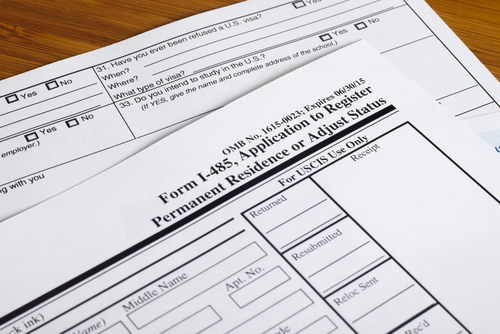

The election cycle of 2016 will be remembered as one in which Donald Trump made immigration a central issue by vowing to build a wall between the U.S. and Mexico, deport 11 million undocumented immigrants, and ban Muslims from entering the country.

The next president should use his or her authority and leadership to reset the debate by de-escalating the inflamed national discourse on this subject and ratcheting down the stakes on immigration policy, with the ultimate goal of passing substantive and durable reform.

The next president should try to de-escalate the rhetoric that has surrounded immigration during the 2016 election cycle.

In this, the next president can take a cue from 18th- and 19th-Century predecessors to act as the cooler head in contrast to the less farsighted Congress and general public. While earlier presidents were severely limited by the constitutional and political landscapes of the time, when the national government’s ability and authority to regulate immigration took a back seat to state and local control, the 45th President will enjoy a much broader playing field.

Particularly after this election, all eyes will be on the president’s first move on immigration. There is opportunity here in that across the political spectrum, remarkable agreement exists that the immigration system is profoundly broken. The first imperative of the 45th president should be a targeted initial action in the first 100 days before turning attention to a longer-term overhaul of the system. However, all actions on immigration should be carried out with a bipartisan group of members of Congress and not via executive action. With the guiding broad principle of de-escalation of conflict in order to get to more permanent reform, the optics and procedural niceties are important.

Political implications

Regardless of what one thinks of Trump’s immigration positions, a significant portion of the American electorate believes immigrants are to blame for the nation’s economic and social ills. Whoever takes office in 2017 will face a divided electorate with some who will continue to demonize immigrants, while others see it as the civil rights cause of this generation. Both parties will have incentives, albeit dissimilar ones, to move on immigration legislation.

For the Republicans, their candidates’ handling of the immigration issue may have done long-term damage to their party brand. They may want to pass legislation to address the concerns of their white working class voters to prevent another populist candidate from capitalizing on this group’s anger in the midterm elections.

For the Democrats, they need to keep Latino and Asian-American voters in the fold who remain ambivalent about President Barack Obama’s deeply unpopular deportation and detention policies.

At a bare minimum, both parties will want to get immigration off the table if only to get to other legislative priorities in non-immigration policy areas.

There are prominent members of the Republican party, such as Paul Ryan, Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, and John McCain, who have indicated support for immigration reform in the past. The new president can tap this spirit among Republicans who may also be interested in repairing his party’s brand. The president may also wish to involve a bipartisan group of congressional leaders who are themselves immigrants.

One of the president’s first appointments might be Margaret Stock, an immigration lawyer, as Secretary of Homeland Security.

One of the president’s first appointments might be Margaret Stock as Secretary of Homeland of Security. She is a member of the Federalist Society, has a deep background in both national security background and immigration policies, former Professor at West Point, and in 2013 won a MacArthur “Genius Grant” prize for her work on immigration issues with military families.

The First 100 Days

In the first 100 days, the president should work with Congress to expedite legislation for a sympathetic group of beneficiaries to show that both parties can come together on immigration. Many might be able to rally around the young people who were brought as minors into the country by their undocumented parents, the DREAMERS, and the idea that one should not attribute the sins of the parents on to their children. The president should work with Congress and Homeland Security to legislatively and administratively transfer all current Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients to Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which allows persons to stay in the U.S. for “extraordinary and temporary conditions,” a status conveyed for humanitarian reasons. TPS status accomplishes the same thing that DACA does: provide work authorization and relief from removal. After all DACA beneficiaries have been moved to TPS status, the president should repealDACA because it has been such a lightning rod and a potent symbol on the right for executive overreach. By undertaking this procedural (and semantic) fix early in the first year, the new president can say that he/she worked with Congress to pass reform rather than going it alone, a clear advantage for either a Republican or Democratic president.

The president should focus on fixing immigration by using the Farm Bill as a framework.

The long game and far more significant fix that the 45th president and Congress should focus on is a lowering of the stakes on immigration by using the Agricultural Adjustment Act (also known as the “Farm Bill”) as a framework. The new president needs to expand the immigration debate to include more than undocumented immigration. Lost in the vitriol of this election’s rhetoric was any discussion of the rest of the vast and complex immigration system. We know from the last successful major overhaul of the system, the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), that substantive reform is more likely when bundling enforcement and benefits into the same bill. The landmark bill passed by the Senate in 2013 also took such an approach. However, the Republican-controlled House killed that bill by divorcing the enforcement provisions and the benefits into separate bills.

De-escalating conflict

Just as the Farm Bill today includes subsidies for agricultural interests and nutrition programs, IRCA had forced together disparate parties, namely enforcement hawks and immigrant advocacy groups, to compromise and ensure passage of the bill. By tying together farm subsidies and nutrition programs, the Farm Bill marries rural interests who need passage of the former and urban interests who benefit from the latter. Admittedly farm and nutrition subsidies have been intertwined since the inception of the Agricultural Adjustment Act in the 1930s and immigration may be a more explosive policy area, but someone had to decide to put the two together. The one crucial feature that the Farm Bill has that IRCA lacked was that it is up for reauthorization approximately every six years, ensuring that the funding levels for the farm subsidies and nutrition program are recalibrated periodically to reflect evolving needs.

By passing immigration reform that needs to be periodically reauthorized, the new system could ensure that temporary and permanent immigration visa category numbers reflect the current national interest.

The new president and the Congress need to pass an immigration reform bill that does not “reform” the immigration system as a one-off, but instead institutes a periodic reauthorization process like the Farm Bill. In so doing, the newly created immigration system, which should include both benefits and enforcement provisions, would simultaneously de-escalate conflict around this policy area; bring a broad coalition together (business, civil rights groups, immigrant/ethnic advocacy groups, and enforcement interests); and ensure that all temporary and permanent immigration visa category numbers as well as enforcement assets actually reflect the current national interest. The alternative is to have substantive reform 30 to 50 years apart (Immigration Act of 1965 and IRCA, respectively) while the nation hobbles along with a system that is unresponsive to the changing needs of American families and businesses.

Historical context

The absence of a clear constitutional source for federal authority over immigration (save specifically for naturalization) had hamstrung past presidents’ initiatives. Unlike the 45th president, who will operate at a time when the national government has consolidated its power to regulate the entry and exit of immigrants, backed by the weight of Supreme Court precedents, the presidents in the 18th and 19th Centuries were limited to reacting to state initiatives. The new president can and should be proactive where his/her predecessors could not.

Until 1882, the Supreme Court treated immigration as a commerce issue, giving Congress more control over the area than the president. Even so, state “police power” over local health and safety concerns trumped the national Congress’ interstate commerce power. Additionally, no national power to regulate the freedom of movement was possible in the antebellum period given the strong desire of the slave states and their congressional representatives to preserve the domestic slave trade and the local laws restricting the movement of free and native born blacks into and across states. These two factors explain why there was only a handful of federal immigration legislation before 1882, such as the Naturalization Act of 1790 (which did not impinge on freedom of movement) and some Passenger Laws regulating the health and safety conditions on ships.

In 1864, when the Lincoln Administration sought to encourage higher levels of immigration to bolster the Union’s Civil War effort and to create a Commissioner of Immigration who would report to the Department of State, it found itself behind the curve. Northeastern seaboard states like New York and Massachusetts had already developed extensive administrative capacities and bureaucratic expertise to screen and admit immigrants, as evidenced by the state-run Castle Garden landing depot in New York city, the predecessor of the federal Ellis Island facility. Meanwhile, interior states like Wisconsin and Minnesota had already developed immigrant recruitment programs overseas to entice immigrants to move beyond the gateway states. In this era, states, not the federal government, innovated.

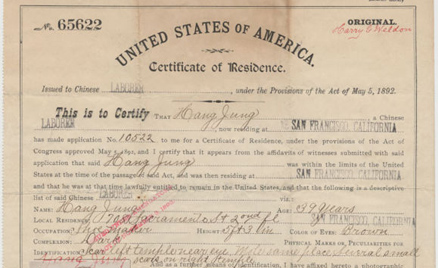

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 restricted the immigration of Chinese laborers to the United States. This photo shows a Chinese American Certificate of Residence from 1892.

When Presidents Rutherford B. Hayes and Chester Arthur were in office, immigration was transitioning to national control and the Supreme Court paved the way by construing Congress as having plenary power over immigration based on notions of national sovereignty. Motivated by labor competition and nativism in California and abetted by fierce national party competition for votes of the western states, Congress passed by large margins in both houses the first national immigration law that singled out an ethnic group for exclusion. President Hayes vetoed the bill, as initially did Chester Arthur, both citing the purview of the Executive branch rather than Congress to abrogate treaties with foreign powers. Arthur aided the consolidation of immigration authority by the national government by emphasizing the foreign policy aspect undergirding the plenary power rationale in his veto. However, he also signaled that he would be willing to sign an amended version of the bill that would assuage some of his diplomatic concerns and be amenable to “the people’s” concerns about the Chinese. The infamous Chinese Exclusion Act was eventually signed into law in 1882 and was not fully repealed until 1943, although other national-origins quotas remained in effect until 1965.

Conclusion

Legislation should not be understood as a science but instead as the best our leaders could do given the political constraints of the moment. The 45th president the United States will be circumscribed by domestic politics—so much so that politics will dictate his or her legislative priorities, process, and personnel. Still, the next president can use the bully pulpit much more effectively than 18th- and 19th-Century presidents who were forced into a reactionary stance by the states. Perhaps the new president can skillfully transform the anti-immigrant appeals of the campaign season and prevent immigration from becoming the new third rail of American politics. Both our national well-being and the vitality of the two parties depend upon it.