To the new president:

You should place immigration and population at or near the top of your agenda for your first year in office. However, avoid comprehensive immigration reform (CIR) schemes at all costs.

Comprehensive immigration reform is dead. Your administration should see it gets a decent burial.

Instead of a futile search for comprehensive reform, you should launch an offensive to broaden the terms with which immigration is discussed. Those terms are exceedingly narrow today because immigration enthusiasts have fought a long and largely winning battle to rule out of bounds a wide range of words and ideas that they believe are offensive or racist (or true but possibly damaging to their cause). At the same time, they have sanctified numerous dubious claims of fact as beyond empirical test.

It is amazing how quickly otherwise sensible people cave in to this extreme form of political correctness. The damage these censors do to the level of public discourse on immigration is difficult to exaggerate. It is also surprising that so many people act as if mass immigration and the demographic changes in its train are Acts of God: Like the weather, it happens and nothing can be done but get out of its way. This turns history on its head and ignores the inconvenient fact that behind all these events is an act not of God but of public policy.

Many will advise you to take up immigration in your first year for the wrong reasons. You should resist proposals to immediately launch an effort to build a majority behind comprehensive immigration reform. It is true that the system is broken and badly in need of repair. Attempts to reform immigration through a comprehensive package of proposals dealing with legal and illegal migration have been stymied for now going on 26 years, since the passage of legislation in1990. Over time, the adversaries in this process have become so familiar that they barely need to trot out their well-rehearsed lines. Anyone unfortunate enough to observe this spectacle close at hand will notice that hardly anyone ever changes their mind.

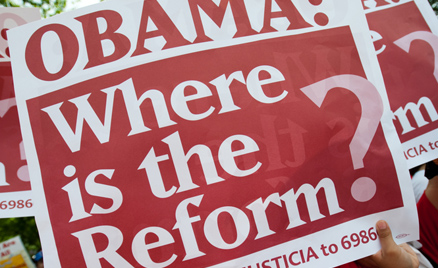

Nonetheless, you will be pressured to try to do what George W. Bush and Barack Obama failed to accomplish: To put together a coalition of members of Congress who are willing to hold their noses and sign off on a bill many of the components of which they abhor. Bush went early in pursuit of CIR only to see his plans go off the rails after 9/11. Obama made promises that led many voters to expect an early offensive on immigration, but he went with health care instead and, after the reversals of the mid-term elections, never got back to his early agenda.

President Obama worked to pass immigration reform but ultimately turned to executive action after the bill was killed in Congress.

Some might see in this prolonged impasse the genius of the “Madisonian” system our Founders bequeathed to us. Legislative give-and-take is rightly praised as a democratic method of dispute resolution. If no majority can be found, no legislation should be adopted. Frankly, we have been well-served by the multiple veto points in our lawmaking process. Better no legislation than bad legislation.

If you undertake to pass CIR, you are likely to either produce nothing (the outcome of the last two presidencies) or draw up some misbegotten stew of enhanced “controls” at the border and the interior with E-Verify, plus a limited path to citizenship for many of the undocumented. If history is any guide, a limited path to legal status will quickly devolve into a mass amnesty, while the promise of stricter controls will not withstand the outrage that will accompany the first deportations. As a standalone proposition, for example, the ludicrous diversity visa program might be voted out of existence. As part of a CIR, it could well be an essential part of a tradeoff to win votes for some other equally questionable provision.

CIR, if adopted, would do more harm than good. It would throw you into an elaborate but banal discussion of technical matters that are worthy in their own right but, if debate over them is at the expense of coming to grips with the looming crisis we are in, they become trivial. But at last there is some good news! CIR has little to no chance of passing. As president, you should refuse to introduce such legislation since it would be a waste of your time. Any CIR that might pass would richly deserve your veto.

The main argument for taking up immigration in your first year, however strong the temptation to defer it until later, is that there is hardly any issue that is more important, and losing a year or more before making critical changes will only deepen the morass we already face. Moreover, the conflict over immigration is at the center of many other issues: state/federal relations, welfare, education, health care, voting rights, and affirmative action.

Context for Rethinking Immigration Reform

As you assume office in January, your administration begins at the coincidence of several alarming developments that we ignore at our peril.

The first is the eruption of global conflict between Islamic fundamentalism and the nominally Christian but predominantly secular West. This struggle has enormous implications for the immigration policies of all the Western countries, the United States foremost. Governments will need to take account of the risks involved in admitting Muslim immigrants who might resist integration and be susceptible to the appeals of radical Islam, against the criticism that would be provoked by a policy that excluded Muslims or subjected them to intensive screening. In addition, the spread of terrorism more often than not involves passports, visas, and crossing borders; often illegally and too often legally. The relative peace and extravagant complacency that made it seem reasonable to create and expand the visa waiver program, for example, are truly vestiges of a simpler time.

Refugees fleeing violence in countries such as Syria will affect the immigration policies of the United States and other Western countries.

Added to the normal tensions between sending and receiving states, immigration policy today is unavoidably caught up in the breathtaking and ominous demographic trends in Western countries. Birth rates are plummeting in the democracies. Thus, it seems obvious to many that population decline cannot be avoided without mass immigration and, therefore, it should be encouraged. There is considerable evidence that to slow or reverse the present decline, Western countries would on average need to add hundreds of thousands of migrants this year and every year far into the future.

But apart from the issue of whether the supply of migrants, so ample today, would remain sufficient to support this scenario, the social turmoil stimulated by much smaller influxes of migrants suggests that deliberate efforts to arrest population decline through immigration are not feasible politically. Yet fertility below replacement means exactly what the bloodless demographic term implies: Absent immigration, the populations of Western countries are in a remorseless death spiral. With mass immigration, deliberate or not, the native populations of most Western countries will be “replaced.”

This reality must be set beside the currently high birth rates in non-Western countries. The conjunction of corrupt and predatory states with rapid population growth is a primary cause of the harrowing gap between living standards across the globe. The income gap is perhaps the main driver of migration out of the poor countries and into the West. Given powerful motives to leave, the potential numbers who would go if the opportunity presents itself are staggering. The current mass assault on the borders of Europe hints at the possible scale of such an exodus.

The Western democracies are well into a migration crisis of epic proportions. That American discussion of immigration policy is almost completely devoid of any mention of the problem is deeply troubling.

Breaking the Policy Stalemate by Focusing on National Interests

Many immigrants who came to the United States arrived through Ellis Island in New York. It was one of the busiest immigrant inspection stations.

The status quo of heated rhetoric, policy drift, and political stalemate cannot be allowed to continue. Too much is at stake.

There is little that the U.S. immigration program can of itself do to alleviate the appalling conditions in the poor parts of the world. As pleasant as some idealists make it sound, the idea that opening our doors to millions of the poor around the world could make a dent in global poverty is nonsense. A realistic immigration policy must seek to accomplish, as best we can, the insulation of the U.S. population and its political institutions from the most menacing of the threats in the world today. Rather than inviting the poor to our shores, and assuming they are all devotees of Thomas Jefferson and believe in the separation of church and state, we should strictly regulate who can enter and for what purpose.

The principle according to which immigration decisions should be made is that they ought to be consistent with our national interest.

There should be a consensus among Americans on this point, but, remarkably, many people believe such a stance is immoral or unwise. Furthermore, they often seem to think that our policies ought to be designed mostly with the interests of the migrant in mind. This sort of thinking must be challenged by your administration. Decisions as to what immigration policies to adopt should always put American interests ahead of the interests of others. Be clear that the humanitarian rescue of genuine refugees is in our national interest. The unquestioning assumption that all the migrants swarming into Europe are genuine refugees is not.

The United States is the most important immigrant-receiving country in the world and one of the most desirable destinations for migrants of all types. We should, therefore, be capable of managing a recruitment and admission scheme that enhances American productivity and technological prowess, enriches the arts, and does not contribute to serious social tensions. Migration ought to be for us what natural resources in petroleum, diamonds, and other scarce commodities are to other states. We have more ready access to human capital than any country in the world. Unfortunately, we seem incapable of exploiting our natural advantage to attract the cream of global manpower. Instead, the design and implementation of our immigration and refugee policy appears oblivious to the self-imposed losses we suffer. The deficiencies of our immigration law that lead to these sub-optimal outcomes are well known. The question your administration must answer is what strategy has the best prospects for eliminating at least the most flagrantly ill-conceived programs?

Immigrants arrive at Ellis Island in 1910. The United States has long been one of the most desirable destinations for immigrants.

When you take office it will be the first time in 50 years that American voters rank immigration among their top concerns. Although there are numerous reasons for its salience, it nonetheless provides you a small political opening. As the newly elected president, you have a constitutional duty to support measures vital to our interests. This will certainly require deft leadership from the White House.

A New Approach to Immigration Reform

A new approach should seize on ideas and principles that can guide reform toward national interests. Doing so requires that, once and for all, we avoid feel-good platitudes that only harden our polarized attitudes on the issue. Among the most commonly deployed arguments of doubtful veracity is the claim that America has been and always will be a country of immigrants. Another is that every new immigrant group is vilified but in the end they turn out just fine. Yes, most are vilified, but no, any impartial study would show that not all turn out just fine. Pronouncements like these ignore differences between settler societies and immigration societies. At different points in our history, the U.S. has been both.

Some assertions are remarkably flexible. For example, immigration is the exclusive prerogative of the central government when the issue is local police cooperation with immigration authorities, but it is not when the issue is the establishment of sanctuary cities. One “fact” that is firmly embedded in our public school curricula is that we have no common culture and, hence, the only glue that holds us together is our assent to the American creed of equality, individual liberty, and the rule of law. This proposition is doubtful on several counts. It is arguable that there was a dominant political culture in America from the colonial period until the last quarter of the 19th Century. Denial of the importance of the Anglo-Protestant culture has the effect of elevating all immigrant cultures to equal status in terms of their contribution to our national development. This is an injustice not only to our founding generation, but also to those immigrant communities that have been more critical to our national saga than others that may have arrived later or in smaller numbers.

These political bromides would be comical if they did not seriously squelch open and honest debate and were their enforcers not eager to damage the reputations of anyone who dares to challenge orthodoxy.

Making headway against these speech codes is a necessary first step to building an immigration system in the national interest. Using your bully pulpit to “just say no” when a falsehood or an arguable claim is made would do wonders for the veracity of our now-fraudulent immigration debate. Most importantly, you will need to assure the immigrant community, broadly construed, that you are not engaged in an assault against immigrants. The very false assumption that the mildest questions about immigration policy are tantamount to a declaration of war against immigrants creates undue stress among immigrants and distracts us from real issues.

What you must say, whether it is warmly received or not, is that immigration policy is not the sole prerogative of immigrants officially or self-identified. It is the common possession of all Americans. There is no chance of serious reform as long as key elements of our immigration past and present are not open to discussion.

If you succeed in the battle of the narratives, a number of more specific proposals will emerge. When assessed against the principle of serving the national interest, it will be easier to separate the wheat from the chaff.

First Steps: How to Use Your First Year

Incremental change should be your goal. A few relatively small initiatives in your first year must take into account the state of public opinion and more importantly the array of organized interests attached to each part of the whole. Small but significant victories could provide the momentum to move on to more controversial changes.

Miami, Florida is home to a large immigrant population from Cuba. A Cuban restaurant in the Little Havana neighborhood is a common sight.

The current chaotic program is the result of the accretion of literally thousands of features small and large over many years. It was not created out of whole cloth and it will not be supplanted by an alternative that seeks to cover all the bases. The hard truth is that American immigration and refugee law makes no sense from the perspective of an organizational flow chart. Means are laid out in considerable detail. Ends are rarely identified. It is sensible only to the extent it delivers important benefits to concrete political constituencies. These constituencies have become entrenched and make no attempt to hide their sense of entitlement to what they see as their vested property rights, nor do they hide their willingness to defend them. As Tocqueville informed us long ago, if I might paraphrase an earlier version of the precept: “It is more blessed to give than to take away what has been given.”

Underneath all the exaggeration, bombast, and sentimentality on all sides, most Americans recognize that immigration is a major part of our national story and that it should continue to play a significant role. Nonetheless, after a half-century of runaway migration, the love affair between immigration and Americans has important limits. Opinion is positive with respect to immigration in the most general sense, but one cannot claim that the public supports the current system as a whole. Indeed, poll after poll indicates that the general public has never advocated increasing the numbers of immigrants admitted annually. The polls render a general verdict that you could cite in support of proposals you might make: The number of immigrants admitted annually should first be contained and then reduced. This, you could honestly claim, would be consistent with the long and frequently expressed will of the majority.

A few specific possibilities for elimination or alteration present themselves, The Cuban Adjustment Act is well beyond its “sell by” date. With the restoration of diplomatic relations with Cuba, the justification for treating refugees from that island differently from those from Haiti or other places looks like racial discrimination and reflects the political muscle of the Cuban exile community in the early 60s. This effort would divide the Hispanic community, which is in any case a fiction created by the government. Rescinding the law would put other constituencies on notice that the old client politics is under duress.

You should put the EB-5 Investor visa on the chopping block. The idea of selling visas to wealthy foreigners is normatively repulsive, a cruel reversal of the American Dream, and, as it turns out, economically a bust.

Although the ocean protects the United States from being overwhelmed by immigrants from the Middle East, the United States should fund the effort to rescue refugees at the level its urgency requires.

Slightly more ambitious would be axing the diversity visa lottery. Everyone may have their own pet reasons for rescinding this program. The most persuasive are the inappropriateness of distributing permanent resident visas by lottery without regard to skill and the implication that everyone in the world has a right to immigrate to the U.S. even if it is impossible to actually admit them all.

One step you might be able to take without much legislative blowback would be to increase the number of consular personnel to process applications from abroad. It is an open secret that new Foreign Service Officers typically spend some time in purgatory processing visas. More personnel would possibly improve morale and reduce errors.

Finally, mass influxes of refugees like the unaccompanied minors three years ago and the Syrian arrivals in 2015 should be closely vetted before being allowed to enter the U.S. This common sense idea should not but probably will provoke a tidal wave of accusations of racism and the bemused shaking of heads by the cognoscenti in the media. They see their role as defending hapless and innocent immigrants from the predations of their not-so-innocent fellow Americans. You should ignore them. You might also seek to use your influence to return refugee protection to its original model of settling refugees temporarily in camps and other territories where their safety can be guaranteed and they can be repatriated as soon as conditions permit. Because distance and oceans provide us some cover from Middle Eastern population movements, we should fund the effort to rescue refugees at the level its urgency requires. Given the heavy burden borne by states in the region of refugee crises (Jordan is a prime example), we should massively increase our foreign aid budget.

Conclusion

The next president should start a conversation on day one to avoid the ugly politics that can accompany efforts to reform the immigration system.

It is important that any efforts to reform immigration be done evenhandedly. The process should be transparent. Some of the most troubling features of our immigration system derive from the fact that they were adopted despite lacking obvious majority support. The 1965 Immigration Act was adopted with a bipartisan majority in both Houses, and signed by President Lyndon Johnson at the foot of the Statue of Liberty. The problem was not that the Act was passed in the middle of the night in secrecy. The problem was that not one of the actual consequences of the law was acknowledged or given a close look. Nevertheless, this law has altered American demography beyond recognition.

We have to concede that as unpopular as some aspects of the immigration system are, other aspects enjoy broad public support. Even were it possible, it would be undesirable to push through legislation in the face of serious opposition or to enact policy by stealth. That is what got us where we are today. You do not want to be the general at the head of an army seeking to take the immigration program apart. That could result in some very ugly politics. That is why you should start on day one to engage the American people in a conversation where the realities of our situation are forcefully and clearly laid out.

Our strategy must be founded on the belief (hope?) that a well-informed public will accept the necessity of slowing down the immigration colossus. If our case is intelligently put and is still roundly rejected by a majority of Americans, so be it. Perhaps our analysis is flawed. Perhaps we can continue to admit more than a million new immigrants from the ends of the earth next year and for years into the future without undue tensions. Perhaps when our largely European-origin populace is replaced by some mix of non-European peoples, our democracy will not only thrive but be enriched. It is an outcome devoutly to be wished.