To the new president:

Almost no one has noticed during this year’s ugly and polarized campaign debates over immigration, but the objective conditions in 2017 could be quite auspicious for putting our nation’s migration management system on a breakthrough path to reasonable health. What is needed is your determined presidential leadership, manifesting clear vision of a balanced and sustainable long-term solution—leadership made vivid by well-chosen administrative innovations.

A successful approach must combine an unmistakable commitment to long-term enforcement with clear and humane reforms drawn from the legalization agenda. The point will be to shock a jaded public into believing that actionable legislative compromise—as well as truly effective, future-oriented enforcement—is actually possible. Your overall approach should include the following elements:

The next president should crackdown on people who have overstayed tourist or other visas, which would bolster credibility in law-enforcement circles.

To get this result—regardless of party—you will have to disappoint, perhaps enrage, some of your party’s most vocal interest groups on these issues, by championing a few measures from the opposing camp’s playbook. This will require an early draw on your post-victory political capital. But if you take a strong stand, hold firm to your vision, and withstand the first few gale-force blowbacks, you have the chance to persuade all but the most militant on either side that their acquiescence will optimize their core goals when played out over time.

Seizing the first year

Mexican migration patterns to the United States have declined over the last ten years partly because of better border enforcement but mainly because of improved economic conditions in Mexico.

Here is why this first year, unlike those of many other presidents, holds promise for immigration breakthroughs. You come into office with the undocumented population already shrinking. Mexican migration patterns have been sharply reduced from what your two immediate predecessors faced, a reduction based partly on better border enforcement but mainly on favorable economic and demographic factors in Mexico that should persist. In significant part because of that reduced flow (as compared to, say, 2005, when the unauthorized population was growing by 800,000), the political climate is also more supportive than one would know from watching the evening news.

Media attention goes to the loud, angry, and passionate activists on both sides. (Sample slogans: “Deport them all” or “Build the wall” on the right; “Not one more [deportation]!” on the left.) But polls over the last few years have shown wide support for a path to citizenship for unauthorized migrants already long resident, while majorities still favor serious border control and (by implication) would seem ready to accept wider interior enforcement directed at recent violators. Another little-known factor is this: The nation’s major investment in immigration controls and systems, developed primarily to counter terrorism after 9/11, created tools that can also be quite effective in curbing ordinary immigration violations, if deployed with imagination.

You also have timing advantages, at least as it now appears, not enjoyed by your predecessors, both of whom initially planned to launch and maybe secure a legislative solution in their first year. George W. Bush shared a somewhat naïve and incomplete policy plan for reforms with Mexican President Vicente Fox in a highly publicized summit meeting held seven months into his tenure, and the two of them said all the right things to move the process along. But that was September 6, 2001—five days before the terrorist attacks. Bush couldn’t seriously reengage on overall immigration reform until 2004.

President Vicente Fox of Mexico and President George W. Bush met to talk about immigration reforms on September 6, 2001, five days before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, which refocused U.S. policy on terrorism.

In May 2008, candidate Barack Obama pledged to push a comprehensive immigration reform bill during his first year in office. But in September the Great Recession thundered in. By the time he assumed office, Obama clearly had to prioritize the economic rescue. To no one’s surprise, he also prioritized the negotiation of his signature (and more heavily promised) health insurance reform ahead of immigration reform. That wound up occupying 13 valuable early-term months. By the time Obama could have turned to immigration legislation, he had already asked supportive lawmakers to take unpopular, difficult votes on the Troubled Asset Relief Program and the Affordable Care Act, and the mid-term elections were drawing near. The moment had been lost.

As of now you face nothing comparable. Knock on wood.

But you will have to make this a top legislative priority; real progress on curing our immigration system’s ills will definitely require legislation. Your predecessor was bold in wielding unilateral presidential authority to ease some genuine human problems through “deferred action,” a form of prosecutorial discretion that, under President Obama’s plans, would essentially assure about half of the undocumented that they wouldn’t be removed. But the sweeping scope of his measures and the absence of any equivalent boldness on the enforcement side exacerbated the polarization. In any case, Obama repeatedly acknowledged that those steps were only temporary and that Congress would ultimately have to act. Even if the Supreme Court overturns a lower court’s ruling and lifts the stay on President Obama’s broadest “deferred action” initiatives, they would still bring only temporary palliatives. You need to keep your eye on a durable fix—and that means legislation.

The Elements

The main pieces of comprehensive reform legislation that can fix our immigration system are well known and generally accepted, even if tepidly. But major disagreements do persist over details and sequencing.

Border control needs to be conceived more broadly to recognize that it requires bolstering by resolute interior enforcement.

These elements were all included in the comprehensive immigration reform bill that passed the Senate overwhelmingly (68 votes to 32) in 2013. It was never brought to a vote in the House, however, largely because of a failure of trust. You need to break through that mistrust, via well-chosen words but even more through creative, sophisticated, and balanced executive initiatives that convey your vision of a new and sustainable enforcement regime focused on recent violators.

The camps

The central flashpoint in the cycle of mistrust has been legalization. Some among the restrictionist camp bitterly oppose any such plan, arguing that it rewards law violation and will just tempt future flows. But there are many others in that camp who might accept the idea in principle, while insisting that they must first see proof that enhanced enforcement will really work. They want assurance that we won’t just legalize the current unauthorized population but then find ourselves back in the same soup a decade down the road, with another 11 million unauthorized residents.

A comprehensive immigration reform plan realistically has to include legalization for long-term immigrants who are in the country illegally.

From these premises has come the demand for “enforcement first.” Implement mandatory E-Verify and other crackdowns first, showing a real track record of presidential commitment to enforcement, and then we can come back and negotiate over legalization.

The enforcement-first crowd believes they have an unanswerable reason for this up-front demand: Look at what happened in 1986 with IRCA. Its promise was to balance legalization with new enforcement measures that would prevent new undocumented flows, assuring a one-time-only amnesty. Legalization worked beautifully to serve its proponents’ objectives, they point out, winning eventual green cards for nearly three million unauthorized migrants by the early 1990s. But the vaunted employer sanctions utterly failed to secure the job market against the unauthorized. In practice, it was all dessert and no spinach. By 2000, the undocumented population had climbed to 8 million, before topping out at 12.2 million in 2007. Fool me twice, shame on me.

Legalization proponents, however, fear that enforcement-first will become enforcement-only. The restrictionists will just keep moving the goalposts that mark when enforcement is good enough to initiate legalization. Meantime, legalization proponents worry, these first stages of tougher enforcement will sweep up and deport many of the long-resident (60 percent of the current unauthorized population has been resident 10 years or more, and approximately one-third live in families with at least one U.S. citizen member). For the pro-legalization camp, enforcement initiatives, especially E-Verify, have to go hand in hand with legalization, so that the long-resident, who have strong ties in this country, can remain employed—and thereby are also able to pay the application fees and fines that will doubtless be conditions of legalization.

An overstay enforcement initiative to dislodge the mistrust

Any immigration reform will need to balance the “enforcement first” camp with the legalization camp, those who want to restrict the flow of immigrants into the country and those who want a path to citizenship for long-term residents.

It will be your task, as president, to break through this mistrust. Mere talk won’t achieve it; demonstrated action can, if done right. Fortunately, you have available several underappreciated tools, developed over the last 15 years through the post-9/11 funding. These tools afford the means to show the restrictionist camp that this is not 1986. The science of immigration control has come a long way in 30 years, even though the messiness of our political deadlock has blocked full deployment in ways that could foster public optimism. And yet the tools are discriminating enough to permit early demonstrations of resolute enforcement without threatening long-staying individuals. Here is one idea about how to proceed.

Visa overstayers are a major contributor to the unauthorized population (comprising as much as 40 percent), though they don’t capture popular attention the way clandestine border-crossers do. The immigration agencies, through Republican and Democratic administrations, have never made overstays a priority for removal, leading to occasional complaints from equality-minded observers about the class-based nature of immigration enforcement. Enforcement always seems to come down hardest on impoverished border crossers, mainly from Latin America, while ignoring the sins of the better-off who can come on student or tourist visas.

You can change that picture. Contrary to some congressional claims, our systems right now provide ample information that would enable enforcement against overstayers. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) learns instantly about persons who depart the United States by air or sea, based on the requirement that carriers supply advance passenger manifests for arriving and departing vessels, with key biographical information. That capacity was wholly absent in 1986. This information can be matched against other data in DHS systems about persons whose nonimmigrant stay periods are expiring to produce a reasonably full list, day by day, of those who should have left but apparently did not.

Issue a directive early in your presidency that commands a highly visible ramping up of enforcement against identified overstayers. To ease concerns of the legalization camp, direct explicitly that the focus be on new violators—recent overstayers identified in the daily lists. Further, DHS officers who go out to find and arrest or initiate removal proceedings against the overstayers would be told that their mission is precise—to pick up the identified overstayers and not to initiate removal against any other potentially unauthorized individuals encountered during the operation. Dedicate a high percentage of DHS officer time to this process.

The Department of Homeland Security could use their systems to identify people who overstay their visas.

A successful campaign to introduce more rigorous enforcement against overstayers is likely to have an early feedback effect that will enhance deterrence. News that visa overstayers are identified shortly after their default and made subject to enforcement will spread among students and tourists, for example. Thereafter, voluntary adherence to the agreed time limits on a temporary admission should become more common among nonimmigrants, helping to build a culture of compliance rather than dismissiveness about the immigration law’s requirements.

A side benefit: officer morale

The last few years have been difficult ones for DHS enforcement personnel, exacerbated by union leadership that has been remarkably acerbic and confrontational with management as DHS has tried to innovate. From the officers’ perspective, the department’s emphasis since about 2011 on systematic exercise of prosecutorial discretion is mainly about what they are not supposed to do, from among actions for which they have been trained and which would be clearly consistent with the statute. A largely new and visible enforcement program, encouraging officer initiative and innovation to locate and remove overstay violators whose names appear on a list generated shortly after the violation occurs, would come as a welcome change, one that would pay officers the compliment of genuinely drawing upon their professional investigative skills. (The passenger manifest check won’t ordinarily generate the person’s current address.) Your overall immigration reform program will benefit greatly from moderating the skepticism of the rank-and-file while, of equal importance, fortifying the position of those officers (and there are many) who see real value in a balanced reform package.

How the overstay initiative could lead to legislative compromise

Having border patrol officers focus on people who overstay their visas would pay them the compliment of genuinely drawing upon their professional investigation skills and improve morale. U.S. Department of Homeland Security

The overstay initiative sketched here may be most useful in breaking through the cycle of distrust if this memo is now being read by a Democratic president. President Obama was not successful in reassuring the enforcement-minded that he would be a good steward of new enforcement powers. And some of the campaign comments of the leading Democratic candidates risk cementing the same early image. Credible commitment to enforcement is indispensable if you are going to piece together a coalition that can enact comprehensive immigration reform and thereby build a stable, efficient, and generous system for the future. This overstay action is one possible ticket to such credibility. Some of the interest groups that are your normal allies will of course denounce it, no matter how carefully you remind them that it is focused only on recent violators, not long-resident de facto members of the community. Wear their condemnation proudly. It will help reinforce your credibility with a wider range of constituencies.

But an initiative of this kind should have relevance as well if the president reading this memo is a Republican. To start with, it does bear noting that the Republican campaign has generated such extreme comments from some candidates that a bridge-building reform package is harder to envision. But there remain many Republicans who really want to put the nation’s immigration divide in the rear-view mirror, through some sort of comprehensive legislation. The party could compete better for the votes of naturalized immigrants and ethnic communities, whose instincts may run in a conservative direction, if the threat of massive roundups of long-resident noncitizens is dispelled. An overstay initiative that focuses on recent violators, and is clearly not a tool to hound the long-resident, could serve this purpose.

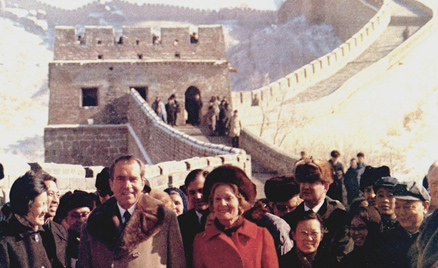

The trust a Republican president needs to win is from among those in the legalization camp. But you also have an easier and more direct path to that goal: Come out full force for an expansive legalization plan. Your own party’s loudest interest groups will denounce you, but this too should be useful in gaining the needed credibility with the other side. The model here is Nixon to China: A Republican president may have the best chance of pulling off comprehensive reform. And you may soften some of the restrictionist denunciations if you use the bully pulpit to emphasize that legalization can actually empower vigorous enforcement by removing from the target zone the most sympathetic cases, which so often generate popular and judicial resistance.

If the next president is a Republican, the model for immigration reform might be President Nixon in China. A Republican president might have the best chance of pulling off comprehensive reform.

Republican or Democrat, in your first year you need to follow a vision of balanced reform that lays the foundation for a stable and sustainable migration management system. Legalization recognizes the reality bequeathed to us by years of deadlock—contributions made by long-standing residents who have become members of their local communities and have many allies there. But legalization really can be a one-time event because we have enforcement tools and resources unknown 30 years ago. Keep in mind those promising objective conditions awaiting you on inauguration day. Make use of them.