If a president gave an Oval Office address and the networks refused to air it, would it make a sound? This is not, most likely, a question that occupies philosophers, but it does cause White House communications staffers to wake up in the middle of the night in a cold sweat. It did, at least, during my time as a speechwriter for President Bill Clinton.

In May 2000, as Congress prepared to settle a consequential question—whether to normalize trade relations with China on a permanent basis—I helped prepare an Oval Office address urging a “yes” vote. The national security advisor, national economic advisor, and White House chief of staff all signed off on the draft after much discussion.

And then, with just 24 hours to go before the Sunday night address, two of the major television networks begged off. The issue, they said, wasn’t newsworthy enough to justify pre- empting prime-time programming. (At 8:00 p.m. on May 21, the time scheduled for the speech, The Wonderful World of Disney appeared on ABC; CBS ran Touched by an Angel; and NBC aired a 1997 movie, Beverly Hills Ninja.) Briefly, the White House considered going forward with the speech, but this was too humiliating a prospect; we knew that the networks’ indifference to a presidential address would trump the speech itself as the news of the day.

The diminishing draw of the bully pulpit is a reality of the modern presidency. President Barack Obama has given fewer Oval Office addresses than any president since Gerald Ford—in part, his aides say, because he views the format as stilted and anachronistic, but also because the networks are less and less interested in offering air time to presidents. “You can only play this card every once in a while,” Dan Pfeiffer, a former Obama advisor, told Politico in 2015.

Of course, the networks are not saying no out of spite; they see it as a sort of self- protection. Mainstream media—not just the networks but cable news channels, too—are losing ground to the countless other choices on other screens, large and small, and presidential speeches do not promise a ratings boost. The average number of viewers for President Obama’s State of the Union addresses, according to Nielsen, was 38.8 million; for George W. Bush, the average was 45.3 million; and for Clinton, 45.6 million. Some viewers, to be sure, have shifted to streaming the speech on their laptops or phones—activity that Nielsen can’t track—but there is no question that it is getting harder to induce Americans to tune in to a presidential speech outside a moment of crisis. Attention deficit disorder is a national affliction—and possibly, by this point, a permanent condition.

At the same time, new platforms present new opportunities. President Obama took that tired and outmoded institution, the weekly presidential radio address, and turned it into a weekly video address, which he posts on YouTube and the White House website. It might not draw an audience on par with “Carpool Karaoke” or the man who climbed inside a giant water balloon, but online video services create, in effect, a permanent library of presidential speeches, instantly accessible and uninterrupted by cable news commentators. The reach of this distribution system is one that pre-digital presidents might have envied; one can imagine Franklin Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan putting it to effective use. But the onus is on presidents to build and hold an audience—by giving speeches worth streaming.

President Obama reworked the weekly presidential radio address and turned it into a weekly video address that is available on YouTube and the White House website.

The fundamentals of effective communication are not really much different today than they were in Roosevelt’s time. (Or Aristotle’s, for that matter.) At the most basic level, leaders should speak in a clear, honest, and compelling way about the challenges they see and the actions they advocate. In a democracy—no matter who might or might not be tuning in—that is a president’s obligation. But rhetorical leadership is not a science, it is (at its best) an art, and understandings must evolve to keep pace with new realities.

In the first year of the next administration, the new president and his or her team can put a little more bully back in the pulpit by applying three basic principles to presidential communications. First, the president should, for the most part, forgo high rhetoric and formal oratory in favor of a more conversational style and greater candor. Second, the president should shake free from the dead hand of tired traditions, especially the State of the Union address as it has (too) long been conceived. And third, because speechwriting is an essential, inextricable part of the policymaking process, the president should fully empower the speechwriting staff.

This is harder than it seems. The presidential podium—the bullet-proofed “Blue Goose”— is, by design, an imposing structure, less a lectern than a national monument. It is useful for making pronouncements, as it gives a kind of grandeur to even mundane moments. But at other times, it can be like addressing a family dinner with a bullhorn: It does not tend to promote an easy rapport. Lyndon Johnson, who was powerfully effective one-on-one or in a small room, rarely sounded like himself from behind the Blue Goose; straining for stature, he appeared overbearing. The problem, of course, is not the podium, but the presidency—an office so far removed from the lives of real Americans that it takes hard and consistent work to narrow the distance. In 1914, Woodrow Wilson admitted to the Washington press corps that he yearned to give the public “a wink, as much as to say, ‘It is only me that is inside this thing.’”

The presidential podium is an imposing structure that gives a kind of grandeur to mundane moments but does not promote an easy rapport.

In the modern era, Ronald Reagan set the standard. He was a master of what Kathleen Hall Jamieson, who teaches political communications at the University of Pennsylvania, has called the “conversational style.” Reagan’s rejection of the familiar, formal tropes of presidential rhetoric—in favor of (seemingly) ad-libbed asides, transitions like “well. . . ,” and sentences that sometimes trailed off—led many Americans, as Jamieson observed in 1987, to “conclude that we know and like him” and that his presidency was “based in common sense.” Bill Clinton, too, insisted on sounding like an actual person. “No, no,” he often complained to his staff, “this is a speech—I just want to talk to people.” Clinton didn’t mean that he didn’t want to give a speech; he wanted to give a speech that didn’t sound like a speech.

The challenge is even greater today than it was in the 1980s or 1990s. The toxicity of the political climate—a cause and a symptom of the stalemate in Washington and so many attendant national problems—has heightened Americans’ distaste not only for politicians but for the language that they use. All those careful, guileful phrases—crafted by committees of consultants—sound, in the worst epithet of our age, “inauthentic.” We have seen, in 2016, the powerful appeal of candidates who speak sloppily, circuitously, even incoherently, in the way that real people sometimes do. In Enough Said, a book about the state of our public language, Mark Thompson—president and CEO of The New York Times Company—worries about the resort to racist and dishonest statements, but he does see one “lesson to learn from the anti- politicians . . . They look and sound like human beings . . . they’re not automata.” The angry populists make weak and dishonest arguments—what the Greeks called logos—but make effective use of ethos, an expression of personal character, as well as pathos, the ability to match the mood of the audience.

For presidents to succeed, they have to be strong in all three areas. It is possible to ground a policy argument in actual evidence while also reflecting something of actual human experience. It is also possible to express authenticity in a scripted speech, so long as the script says something resonant and true. This is the daily work of rhetorical leadership. It should also be leavened, where possible, by genuinely unscripted, unmediated moments—direct engagement with the public. There is, of course, political risk in every such encounter. But again, as the people have made clear this past year, their trust, like their votes, will have to be earned.

On July 2, 1932, Franklin Roosevelt boarded a Ford trimotor airplane in Albany and flew to his party’s national convention in Chicago, where he accepted its nomination in person, rather than maintain the practice of awaiting the news on one’s front porch in feigned ignorance. “Let it be from now on the task of our party to break foolish traditions,” Roosevelt told the delegates.

The presidency is a two-century-old institution; some of its traditions provide continuity with the past and a source of stability, however symbolic, in times of change. The White House residence itself, home to every president since John Adams, is one of those. But other traditions become a kind of dead weight, a burden that the past, however unwittingly, imposes on the present. The greatest presidential communicators—Roosevelt, of course, among them—have been innovators, willing to alter or abandon old, tired rhetorical customs.

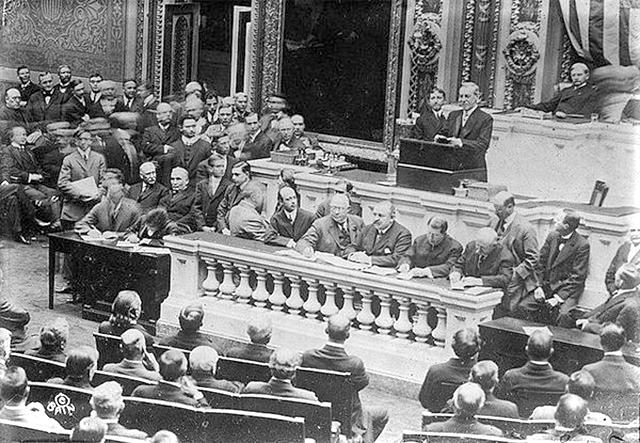

Woodrow Wilson, in 1913, became the first president in more than a century to present his report on the State of the Union as an oral address rather than a written statement; he hoped to convey, as he told members of Congress, that “the president of the United States is a person, not a mere department of the government hailing Congress from some isolated island of jealous power, sending messages, not speaking naturally and with his own voice . . . he is a human being trying to cooperate with other human beings in a common service.” FDR, 20 years later, delivered the first presidential “fireside chat.” These relaxed, informal, occasional speeches, broadcast to 60 or 70 million “friends” (as he called them) across America, “bound them to him in affection,” as his secretary of labor, Frances Perkins, later recalled. And President Obama, embracing Roosevelt’s spirit of “bold, persistent experimentation,” created a White House Office of Digital Strategy, live-streamed the State of the Union address on the White House website, and “enhanced” the speech with interactive slides, posted in real time.

In 1913, President Woodrow Wilson became the first president in more than a century to present the State of the Union to Congress in person.

We have, today, more traditions worth breaking. The State of the Union address would be a good place to start. Within the White House, it is widely acknowledged that the State of the Union is a joyless, and largely pointless, exercise. In an era of chronically bitterly divided government, the speech has lost much of its ability to set the legislative agenda for the year ahead. You would not know this from listening to it, however. It is almost invariably overlong, loaded with wish lists of disconnected policies, and punctuated by artificial applause lines (telegraphed with cues like “Make no mistake”). Every year, it confirms Newton’s law of inertia, which states, in part, that an object in motion stays in motion with the same speed and in the same direction unless acted on by an unbalanced force. This is a speech in need of an unbalanced force. It is a ritual in search of a rationale—beyond the inconvenient fact that Article II, Section 3, of the Constitution requires the president to report to Congress “from time to time” on the state of the union.

But the framers, in their wisdom, left the precise form of that report up to the president. Almost every year, recent presidents have promised that this time, the speech won’t be a laundry list and might actually have a theme, but none seems to have had the courage of his convictions. In 2016, President Obama gave a State of the Union address—the last of his presidency—that proposed few new policies and made an extended, if somewhat unfocused, argument for greater civility in our national life. The next president has an opportunity to improve further on the form, giving a shorter and crisper and more purposeful speech. While the audience may be smaller than it once had been, it is still likely to be tens of millions strong, and many of those Americans would relish a reason to applaud with enthusiasm. Richard Goodwin, who wrote speeches for Lyndon Johnson and both John and Robert Kennedy, has said that the purpose of political speech is to “move men to action and alliance.” That is a fine goal, going forward, for this policy address.

When the great Ted Sorensen, who worked with President John Kennedy on his inaugural address and nearly all of his major speeches, published a memoir in 2008, he gave it the title “Counselor”—not “Speechwriter.” Sorensen—and, indeed, Kennedy—understood his role as one that transcended writing, for the shaping of presidential speeches is the shaping of presidential policy. That status was not unique to Sorensen: Sam Rosenman was Franklin Roosevelt’s chief speechwriter and one of his closest advisors, and Harry McPherson, as special counsel to President Johnson, wrote and edited many of his most memorable addresses while advising LBJ on strategies to deescalate the war in Vietnam and repair race relations in a time of violent unrest.

Harry McPherson was a special counsel to President Johnson and wrote and edited many of the president's most memorable addresses while also advising him on policy.

It was Richard Nixon who formalized the speech-writing process, creating a Writing and Research Department. At the same time, he disempowered the writers, who lacked guidance and access; they dealt with the president mostly through his chief of staff. Reagan, too, established a fire wall between speech writing and policy, leaving his writers to intuit his thinking on crucial questions and leaving his speeches frequently riddled with holes and stuffed with rhetorical filler. “If you think he sounds stale,” his speechwriter Peggy Noonan complained to a colleague, “it’s because the speechwriters haven’t met with him in over a year.” Bill Clinton mostly repaired the breach, working closely with his writers and giving them a seat at the table for all key discussions of policy and strategy. Bush and Obama followed suit, and gave more effective speeches for it.

But the Johnson-McPherson partnership, half a century ago, was the last of its kind. Since then, nearly every White House function has been specialized and subspecialized, and the pace and volume of work in the modern White House might well make it impossible for anyone to inhabit the dual role that McPherson, Sorensen, or Rosenman did. Still, the start of a new presidency is the right time to reaffirm that speech writing is policy making, and to ensure that the president’s writers are empowered with all the information and access they need in order to advance, and help shape, the president’s agenda.