The digital world is changing quickly, and the way people consume information digitally is moving at lightning speed. For example, chances are you are reading this on a smartphone—something that wouldn’t have been true just a few years ago. Today, nearly three-quarters of all Americans own a smartphone, and two-thirds of us prefer to use that smartphone rather than a computer to access the Internet. According to Google, we check our phones about 150 times a day, spending a daily average of 177 minutes on them— which means that most of us check our phones for only about a minute at a time, but repeat that habit dozens and dozens of times a day.

Google calls these “micro-moments”—defining them as “I want-to-know moments, I want-to-go moments, I want-to-do moments, and I want-to-buy moments”—and they have transformed everything from corporate marketing and nonprofit fundraising to traditional news delivery. Micro-moments take place when people grab their smartphones to answer a question, learn a fact, watch a video, or make a purchase.

Recent research shows those micro-moments are affecting political decision making and voter behavior more than ever before, rapidly transforming the nature of political communications strategy. If it wants to "win" its first year, the next White House must master these trends from the start in order to build trust and support among voters. If not, the new administration risks being left behind by the increasingly media-savvy American electorate.

Let’s start with the number of Americans who increasingly access political news on social media through a mobile device.

Barack Obama was the first president to use social media successfully, employing Twitter and Facebook to communicate with hard-to-reach audiences.

In the not-too-distant past, many of us got our political news either from the print copy of a local newspaper on our doorstep at daybreak or from the broadcast networks’ nightly news. There wasn’t a whole lot of choice. These days, we curate our own content.

“We watch what we want, when we want it, on whatever platform we want, on whatever device we want,” explains Celie O’Neil-Hart of YouTube, referring to voters as “video neutral.” As a result, she says, “They don’t care whether they’re watching video online or on television. They care that it's in front of them right now.” In addition, much of our content comes to us through news feeds, referred to us by our social streams and our filtered preferences, and is the product of algorithms, browsers, and even personal relationships.

This changing landscape calls for a two-step strategy. First, the next White House should prioritize influencing traditional news outlets in its first year, since the original source of much of the news that many people consume remains traditional, credible news organizations, although they are not encountering those reports by visiting nytimes.com or watching CBS Evening News. Instead, they are finding those reports through social media on a variety of devices and platforms.

Margaret Brennan, CBS’s White House correspondent, emphasizes the need for nuanced, analytical coverage of policies and initiatives—something traditional news sources can deliver, but Twitter and YouTube cannot. “YouTube and Snapchat can be good at generating interest, but not deep analysis,” Brennan says. “You need traditional media for that.”

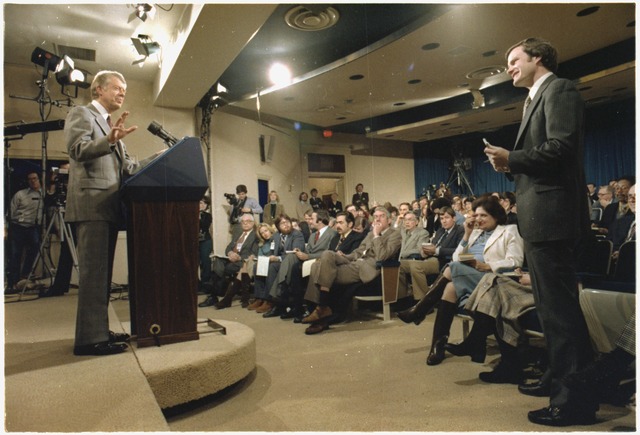

If the next White House wants to win over the public on a variety of issues, the smart move would be to start by increasing, not decreasing, the number of presidential press conferences, and expanding press access to top White House officials. This may also help drown out some of the less-than-credible news outlets that make it into some voters’ news feeds.

The White House will also need to go a step further to meet citizens in that micro-moment when they break out of the bubble of their newsfeed to search for information. To do that, administration officials need to provide content that matches the medium, so that it’s not only easy to find but trustworthy.

The next White House should start increasing, not decreasing, the number of presidential press conferences.

Citizens are hungry for issues-oriented news and information, and as 2017 approaches, they increasingly want that information on a phone. The 21st Century equivalent of what used to be known as a white paper—the PDF file—takes time to download, cannot be cut-and-pasted to share with friends, and often cannot be found by search engines unless the user knows its title and author. It’s no wonder that one-third of all the PDFs published by the World Bank between 2008 and 2012 were not opened by a single person. (The World Bank published that fact in a PDF file. I am not making this up.)

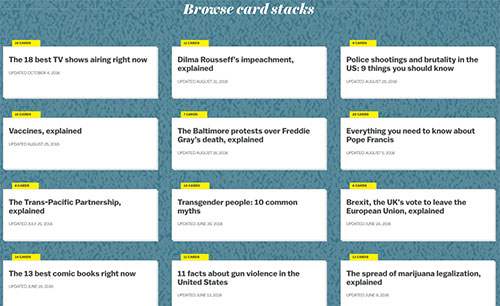

Instead, the next White House should consider creating card stacks the way vox.com does, which convey long-form content through a series of cards that readers can click through and then easily share.

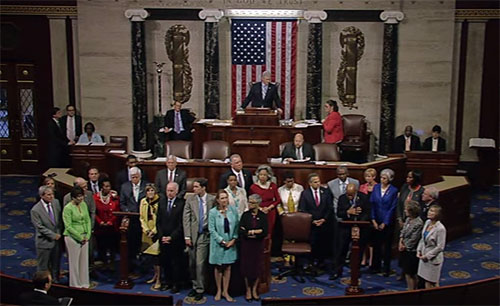

Video also needs to be adapted to this new mobile environment. Live-streaming of political rallies and speeches on Facebook Live is gaining in popularity this election cycle, and offers a great example of giving voters what they want without the filter of the mainstream media. One live-streaming app, Twitter’s Periscope, allowed Democrats to broadcast their sit-in on the House floor last spring, giving them a new political tool when the TV networks’ attention strayed elsewhere.

In June 2016, Democrats in the House held a sit-in to protest for a vote on gun safety legislation. After the cameras were turned off, the Democrats used Periscope and Facebook Live to broadcast their sit-in.

Rather than uploading 45-minute videos of speeches and panel discussions, the next White House should take a page from TED Talks, which publishes videos with crowd-sourced transcripts in both English and Spanish, along with time marks alongside the text. That way shorter clips can be shared easily, embedded in other media, or combined into a highlights reel.

Another example: In November 2016, the congressional commission studying the feasibility of establishing an American Museum of Women’s History is set to issue the first-ever digital report to Congress. Instead of sending a dusty, phonebook-sized report to the Hill and the White House, the commissioners have designed a microsite complete with computer animation, short video clips, and drop-down menus for readers to drill down for more information. It’s all optimized for mobile devices and intended for interested citizens to share with friends to help build momentum for the proposed museum.

Media Theory’s James Kimer, the creative force behind that congressional report, emphasizes the importance of continuing to adapt to the latest platform.

“Citizens used to get their information from newspapers and television, then moved toward websites, and are now in a very dynamic social space,” he says. “The next move will probably be to messaging apps that are growing explosively, like WhatsApp and its interactive news chatbots. But it’s one thing for agencies to use social media for customer service; it’s another to try to raise awareness of public policy issues and build an audience. That’s a tough nut to crack.”

As good as the Obama Administration has been at using social media, the next administration will have to be even better in its first year if it wants to use social media to build community and common ground. The worlds of business and media figured out a long time ago how to expand audiences and gain loyal customers through social media. Public policy makers can do the same if they are willing to change the way they connect with citizens.

Spontaneity, unscripted moments, behind-the-curtain views—anything other than administration talking points delivered on a teleprompter or as a PDF file—are wildly popular. For example, one of the most popular podcast series now is Keeping It 1600, an informal, behind- the-scenes political chat between former Obama staffers Jon Favreau and Dan Pfeiffer. Sidewire, a mobile app, hosts regular on-the-record, unscripted, 250-character text-based conversations between political newsmakers. Snapchat Discover allows sponsors (CNN and BuzzFeed, for example) to post video-with-text stories that have a very behind-the-scenes feel.

The most successful podcasts, Snapchat stories, YouTube videos, BuzzFeed lists, Vox card stacks, and LinkedIn posts are about more than just the platform. They match the message to the medium, which adds to the feeling of authenticity. For example, a 500-word take on the top trends in health care works well on LinkedIn—and could even be sliced into an embeddable card stack— but wouldn’t be so great read out loud on a YouTube video. The best podcasts are either conversations between two people (think of NPR’s Fresh Air) or informal TED-style monologues—and the less slickly produced, the better. Matching the culture and tone of each social media platform adds to the sense of trustworthiness and authenticity and increases the chances that content will go viral—all of which are vital if the goal is better coalition building and community organizing.

Successful media matches the message to the medium, which adds to the feeling of authenticity. Vox.com creates card stacks to explain long-form content through a series of cards that can be easily shared.

To build a governing majority in its first year, the next White House needs to make it easy for existing communities to share its content with people who align with its policy priorities, even if they are not typical supporters. To do that, Internet pioneer Tim O’Reilly, in his essay #Socialcivics and the Architecture of Participation, has argued that “the right way to energize social media isn’t to try to find people to tout your products. It’s to find people who care about the same things you do, and to tell a story that amplifies their voice because it helps people who haven’t yet heard the word also come to know and care.” In fact, O’Reilly writes, “real engagement with the people who care about the issues that the administration is trying to advance is far more effective than broadcasting administration messages and talking points, and hoping they get repeated.”

The idea is to break out of the echo chamber of one’s own supporters and engage with new communities to build broader coalitions when the right moment comes. Policy makers can anticipate when voters will be looking for information on specific issues by keeping up with Google Trends and its sister page, Trending on YouTube. The White House should have persuasive content ready to go based on upcoming 2017 “firsts”—whether those are the administration’s first budget, first Supreme Court nominee, or even first state dinner.

One platform for thought leadership might be LinkedIn Pulse, a mobile app that is fast becoming a vehicle for policy analysis and think pieces from experts looking to influence others. LinkedIn offers a huge platform of more than 450 million members, split almost evenly between Republicans, Democrats, and independents, and it is used by 92 percent of congressional staff, 87 percent of White House staff, 82 percent of cabinet agency staff, and 76 percent of state legislators. Not surprisingly, LinkedIn is the one social medium that has more members who are older than 50 than under 25. Andrew Phillips, who is heading LinkedIn’s outreach to center-right groups, campaigns, and coalitions, points out that LinkedIn is fast becoming the top social media destination for policy and news content on the Internet. The next White House, as well as the House and Senate leadership, would be smart to get on board to maximize their ability to convey long-form content to millions of citizens in 2017.

LinkedIn offers a huge platform of more than 450 million members, almost evenly split between Republicans, Democrats, and independents.

With trust in government so low, connecting with reliable assets such as LinkedIn contributors or popular podcasters could be a way to reach the many Americans who are not visitors to whitehouse.gov and probably never will be.

It’s been well documented that legacy media outlets are suffering from declining readership and waning trust, but the White House press corps must remain part of the next administration’s first-year communications strategy, since those outlets create much of the content on voters’ news feeds.

What’s changing in Washington is the burgeoning amount of political news that is passed on through social media links on a phone—triple the amount shared on a phone since the last election cycle—especially in those I-want-to-know micro-moments. The next White House would be smart to provide its best arguments in easily accessible, findable, and shareable formats. It if does, there’s an opportunity for policy makers to disseminate content targeted for different ages and demographics, tailored to different mobile platforms, to voters who may not be looking for White House–branded content but will grab it when they need it.

In many ways, it’s old-fashioned public outreach and coalition building, but in the palm of citizens’ hands.