Years of neglect have resulted in America’s infrastructure becoming one giant pothole. Nearly half of our major urban highways are choking in congestion, costing drivers $160 billion annually in wasted time and fuel. A quarter of our bridges are in need of repair or modernization. Only three East Coast ports can accommodate the enormous ships that will become the norm now that the newly widened Panama Canal has opened. Our air traffic control system relies on World War II–era technology that delays air travelers and wastes fuel. The average American family loses $3,400 per year in disposable income due to inadequate infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers has graded our transportation network a D+. And in 2015, the World Economic Forum ranked the economic competitiveness of U.S. infrastructure at No. 11. We were ranked No. 1 in 2005.

To compete on a global scale and provide our citizens with the quality of life they have come to expect, the United States must have a first-rate infrastructure. This means our road, bridge, transit, aviation, port, water, electric grid, and broadband networks must be able to accommodate current and future demands. Essential actions the next administration should take include the following:

Leadership matters. The president commands the bully pulpit. Leadership takes vision to see the big picture and courage to do the right thing. To convince the American public and skeptical policymakers, it is imperative that the president use political capital to push for a new vision of transportation. Unwillingness to make and stand by hard choices—especially when it comes to revenue—will derail any successful implementation of a new infrastructure vision. While the recent political climate in Washington has not been ideal for forging legislative compromises, infrastructure policy has long been an area ripe for finding common ground. After all, there are no Republican roads, nor are there Democratic bridges.

The long-term plan for America's infrastructure should include maintaining our existing mass transit systems, such as the Washington, D.C. metro.

When it comes to infrastructure policy, the first order of business should be to draft a long-term, robust, and sustainably funded infrastructure plan. America needs a visionary, strategic infrastructure plan, not another short-term bill that doesn’t even begin to cover the cost of repairing potholes. This plan should cover a 10-year time frame, identify clear national goals, and set priorities for funding. Such a plan would jump-start needed infrastructure projects, revitalize the American economy, and boost employment in construction and related industries.

The long-term plan for America’s infrastructure should include the following:

For such a long-term strategy to be taken seriously on Capitol Hill, it must include viable options to fund and finance it. For more than 50 years, the federal gas tax—one of the purest examples of user fees—has funded America’s roads and bridges. However, this user fee has not been increased since 1993, and when adjusted for inflation, it has lost a third of its purchasing power. It is worth only 11.5 cents today. Over the past 23 years, cars have become more fuel efficient while hybrid and electric vehicles using little or no gas have been on the rise. This perfect storm of decreased revenue and more fuel-efficient cars has drained the Highway Trust Fund, and as a result, revenue has not kept pace with growing transportation needs. For every one-cent increase in the gas tax, $1 billion in revenue is raised. Therefore, to meet our infrastructure needs, the gas tax must be increased by at least 10 cents per gallon.

To improve the nation's infrastructure, user fees such as tolls must be included in the funding and financing options.

Before 1993, votes to increase the gas tax in Congress were a bipartisan affair. In 1982, Congress approved a four-cent hike by a vote of 54 to 33 in the Senate and 180 to 87 in the House. The legislation was signed by President Ronald Reagan. In 1993, Congress included a 4.3 cent increase in the Omnibus Reconciliation Act that President Bill Clinton signed into law.

However, the gas tax is not sustainable as a long-term solution, and other options must be explored. Several states, most notably Oregon and California, have moved forward with pilot programs to test the feasibility of replacing the state gas tax with a charge based on the number of miles a motorist drives. Other states are in the early stages of exploring this concept, and the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act has provided $95 million in grants for further investigation.

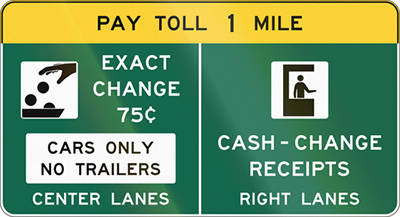

Other funding and financing options must include establishing a national infrastructure bank or authority that can leverage investment from the private sector; removing federal impediments on user fees such as tolls and congestion/variable pricing; increasing or removing the cap on private activity bonds; bringing back Build America Bonds; and encouraging public partnerships with the private sector where they make sense.

The federal government cannot go it alone when it comes to footing the infrastructure bill. State and local governments account for 75 percent of total public spending on transportation and water infrastructure, and the federal share is 25 percent. It is clear that all levels of government and the private sector must work together.

In the next decade, it will be a significant undertaking to adapt the country's infrastructure to a future of driverless, or autonomous, cars.

Along with road user charges, some states have looked for ways to leverage private investment and address common regional infrastructure challenges. For example, Washington, Oregon, and California have joined with British Columbia to establish the West Coast Infrastructure Exchange. The exchange is working to consolidate smaller infrastructure projects that individually could not attract enough public and private financing. As a result of the success of the West Coast Infrastructure Exchange, other regions of the country, such as the Mountain West, the Northeast, and the Mid-Atlantic, are exploring similar exchanges. The new administration needs to encourage and incentivize such innovations.

A significant part of the next president’s infrastructure agenda must address the rapid advances in autonomous vehicle technology. Several car models already sport lower-level autonomous features such as vibrating seats or steering wheels if a car strays from its lane. Some models are even capable of parking themselves. However, great strides are being made in advancing higher levels of automation, and companies such as Google have been testing fully driverless cars. It is vital that the next administration ensures that relevant regulations and laws address such critical issues such as liability, safety, and privacy. Several states are starting to pass their own laws, but federal guidance is sorely needed.

Many U.S. cities and towns have been transforming their transportation networks to include more bike-friendly options.

Adapting our infrastructure to a future of driverless cars is going to be a significant undertaking in the next decade. In some cases, more driverless cars will mean that cities won’t necessarily have to build more roads to accommodate rising demand. Autonomous vehicles will mean installing smart technologies into our infrastructure or making travel more efficient on highways by narrowing the lanes. Driverless vehicles that can “talk” to each other and the surrounding infrastructure will substantially increase road capacity, and this communication capability will allow for tighter spacing between cars. This communication capability should improve safety, and accidents will be significantly reduced. Additionally, using technology to variably price crowded roadways will enhance mobility performance by effectively managing traffic flows and providing a more reliable trip.

Mayors across America have been transforming their cities by making them more pedestrian and bike friendly and by using advanced technology to reduce congestion. Some of these advances are due in part to federal grants and others come from public-private partnerships. For example, the Tampa Hillsborough Expressway Authority was awarded a $17 million grant by the U.S. Department of Transportation to deploy a variety of connected vehicle technologies that will outfit cars with communication devices to exchange safety and traffic information with each other and with crosswalks, traffic signals, and other elements in the infrastructure. These types of competitive grants are essential to showing how our urban landscapes will be transformed by advances in technology.

The air traffic control system in the United States still relies on World War II technology. The next president should prioritize funding to update to a satellite-based system.

While improving the condition of America’s roadways and bridges will require significant attention, other modes of transportation must also be addressed, such as improving passenger rail service and prioritizing funding for high-speed rail in corridors that have the population density and proven ridership necessary to make these new systems economically viable. For example, the Northeast Corridor from Washington, D.C., to Boston is ideal for a high-speed rail project, as it is the nation’s densest and most economically productive corridor, with 55 million people and a $2 trillion economy. The other high-density and economically important corridor is between Los Angeles and San Francisco. While $10 billion in federal dollars is being paired with state funds, the project has been slow to get started. The next administration should focus resources on moving this key project forward. To make a high-speed rail corridor a reality, robust dedicated funding and political will is necessary. Forging financial partnerships with the states in the corridor is an essential component of this strategy.

When it comes to air travel, there is much room for improvement in the United States. In 2015, more than 800 million passengers traveled through American airports and the Federal Aviation Administration estimates that this number will top one billion in 2029. More often than not, passengers are traveling through airports that are in dire need of modernization. According to the Airports Council International - North America, there are more than $75 billion in annual capital needs at America’s airports. In addition, our air traffic control system still relies on World War II–era technology to move airplanes. The next president must prioritize funding to hasten the development and deployment of Next Generation (NextGen) satellite-based air traffic control. When fully implemented, NextGen will allow more aircraft to safely fly closer together on more direct routes. Along with increasing the capacity of the air network, NextGen should reduce delays, improve safety, and benefit the environment by reducing fuel consumption, carbon emissions, and noise.

Now that the newly widened Panama Canal is open and operational, America’s ports must be ready to accommodate the larger post-Panamax ships that will become the shipping industry’s standard. While West Coast ports are ready for the bigger ships, only three East Coast ports—Baltimore, Norfolk, and Miami—are deep enough to accept them. And having sufficiently deep channels is only part of the challenge. Land-side infrastructure must be capable of moving millions of tons of goods quickly and efficiently to and from the port. Currently ports are loading and unloading ships that carry 5,000 containers, but the new super ships will hold up to 14,000 containers. Handling this significantly increased volume will require upgraded roads, rails, bridges, and tunnels to move the freight. According to the American Association of Port Authorities, expanding land-side infrastructure will cost nearly $30 billion over the next decade.

Increased financial commitments from all levels of government and a plan to better leverage private sector investments for our ports will be necessary to maintaining our competitiveness. Again, successful competitive grant programs like TIGER can jump-start needed investments at our ports.

In some respects, our nation’s transportation system has remained unchanged for 20 years, but in other ways, it is changing at warp speed. Rapid advances in technology require new and different thinking. We must adapt by building, optimizing, and maintaining a 21st-century transportation network that enhances America’s economic competitiveness and improves our quality of life. Building the infrastructure that our country needs will require vision, political capital, and the willingness to work with both sides of the aisle, and the next president will need to forge partnerships with governors and mayors as well. The new administration will have an immense opportunity and responsibility to make these transformations happen.