Every modern president has dwelled in the shadow of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s extraordinary beginning amid the worst economic crisis in the nation’s history. The confidence and energy with which he tackled the Great Depression during the critical early days of his presidency set the standard by which all subsequent presidents would be judged. FDR’s emergency action to stanch the banking crisis during his first week in the White House was capped dramatically by his first fireside address of March 12, 1933. He explained clearly in a warm conversational tone what he had done about the banks and why he had done it, and the country was dazzled.

Even his ostensible opponents were immensely impressed. An “incredible change has come over the face of things here in the United States in a single week,” editorialized the business-friendly Wall Street Journal, because “the new administration in Washington has superbly risen to the occasion.” The Journal hastened to add that only “a good beginning had been made” and “incalculable risks” remained. But as the editors wrote, with more foresight than they knew, “there are times when a beginning is nearly everything.”

What time is it?

Most first-year presidents, of course, cannot aspire to FDR-like leadership. Rare are the moments in American history when presidents can successfully pursue, as Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Paper, No. 72, “extensive and arduous enterprises for the public benefit.” As Stephen Skowronek has counseled, presidents must ask, “what time is it?” Is the “political time” one that warrants transformative ambitions, like the Civil War and Great Depression, or must the incoming president settle for more prosaic, incremental possibilities in less remarkable times?

Alexander Hamilton, shown in this 1792 painting by John Trumbull, was one of the authors of the Federalist Papers, a series of essays and articles that advocated for the ratification of the U.S. Constitution.

Even if faced with the latter, no modern executive can avoid public expectations, encouraged by the mass media, to demonstrate during the first year that his or her elevation to the White House marks a new chapter in the country’s history. Presidents might try to resist the current practice of journalists and pundits to compare the start of their administrations to Roosevelt’s First Hundred Days during which FDR, building on his extraordinary first week, planted the seeds of the New Deal welfare and regulatory state. “Someday a president-elect might feel that he could say to newsmen (and himself), ‘There won’t be any Hundred Days ... we don’t yet understand how campaign pledges fit events and trends as yet unknown to us, that’s what four years are for,’ ” the dean of presidential scholars, Richard Neustadt wrote wistfully in his 1990 book Presidential Power and the Modern Presidents. It is very unlikely, however, that a president can afford to say “wait until next year.”

William Galston, deputy domestic policy advisor for President Clinton, participates in the Miller Center’s oral history project.

The first 365 days, including such key moments as the inaugural address, the staffing of the administration, and the first encounters with Congress and the bureaucracy, entail promise and peril that establish the cornerstone of a president’s time in office. Even H.W. Brands and Peter Wehner—fervent preachers of modesty—counsel that the president must “shape public opinion” and “tell Congress and the American people what they want to accomplish and take the first steps toward achieving their goals.” As Michael Nelson reports from the Miller Center’s William J. Clinton Presidential History Project, Clinton-era domestic policy aide William Galston argues that the absence of transformative programmatic possibilities demands not reticence but laser-like focus on priorities. Galston makes the case that Clinton’s decision to emphasize “fiscal prudence” over “public investment” during his first year helped him meet the paramount challenge of his presidency: “fixing the economy.”

The dilemma of the modern presidency

The most difficult task newly elected presidents confront is balancing the political demands of party leadership and the responsibilities of what FDR optimistically called “enlightened administration.” Beginning with the Progressive-era presidencies of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson and advancing dramatically with the New Deal, the White House became responsible for orchestrating domestic and foreign policy. The president, not the parties or Congress, was to be the principal instrument of American democracy—in TR’s alluring phrase, “the steward of the public welfare.” Taking account of this development, Elaine Kamarck urges incoming presidents to focus less on “communications, messaging and politics”—the activities that dominate their campaigns—and think more seriously about the “managerial presidency”: how to organize a White House and cabinet to effectively administer the labyrinthine bureaucracy and avoid conspicuous failures.

Still, the Progressive conceit that “neutral competence” could transcend partisanship has never been a reality of modern American politics. The emergence of the “steward of the people” did not subordinate politics to administration. Rather, especially since Ronald Reagan posed the first fundamental challenges to the liberal state, administrative politics has been the norm. With the unraveling of what Arthur Schlesinger once called the “vital center” of American politics, presidents have politicized more than managed the national security and welfare states. This has not only led to an emphasis on White House communication, but also to the concentration of political and policymaking power in the hands of presidential staff who do not have to be confirmed by the Senate. In their 2012 book “The President’s Czars, Mitchel Sollenberger and Mark Rozell showed that these positions have been a staple of the modern presidency since FDR created the Executive Office of the President. But they grew dramatically during the George W. Bush and Barack Obama presidencies.

The White House and the Department of Health and Human Services implemented the Affordable Care Act but the process was turbulent.

The politicization and centralization of administrative authority is at the heart of what Wehner calls the “great paradox” of the contemporary White House: the modern presidency is the “most powerful office in the world,” yet to assume that events can be “shaped like hot wax can set you up for an endless series of frustrations.” Such audacious insularity—what Wilson called the “extraordinary isolation” of the president—was a major factor in the Obama administration’s turbulent implementation of the new federal health insurance marketplace that was so crucial to the success of the Affordable Care Act. The West Wing—more specifically the White House health care czar, Nancy-Ann DeParle—was in charge. But the nuts-and-bolts work fell largely to the Department of Health and Human Services, especially the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. The result was a fragmented process that failed to establish essential connective tissue between White House planning, bureaucratic management, and construction of the project’s technical underpinning. Adding to the chaos, while Congress and the states were expected to play a critical part in the development of insurance marketplaces, they were largely kept in the dark about controversial regulations and technical difficulties.

The next president should seek to establish a less centralized and insulated West Wing. He or she should take advantage of the president’s first year to build a strong cabinet and foster strong ties with Congress. As Washington has become more polarized and the president is more likely to face a Congress controlled by opponents, it has become especially difficult for new presidents to cultivate relationships with members of both parties. Indeed, the growing party divide has accentuated the pathologies of the modern presidency, and all of the essays in this collection recommend that the president spend his or her first year seeking to treat the malady of political rancor. Brands’ essay reminds us of Thomas Jefferson’s famous utterance in his first inaugural address, after a bitter election that had badly rent the nation: “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.” Even transformative leaders who undertake a thoroughgoing remaking of American politics must view, as Jefferson put it, “the whole ground.”

The first year and executive-centered partisanship

It remains to be seen, however, whether the new occupant of the modern executive office can truly view—and successfully navigate—this complex political terrain. George W. Bush promised to be a uniter, not a divider; Obama’s extraordinary elevation to the White House was fueled by his oath to transcend red and blue America. In spite of these assurances of transcendental leadership, Bush and Obama presided over developments that have wrought the most polarized polity in modern American politics.

Our new executive-centered party system is characterized by high expectations for presidential leadership in a context of widespread dissatisfaction with government, strong and intensifying political polarization, and high-stakes battles over the basic direction of domestic and foreign policy. Executive-centered partisanship has been greatly abetted, furthermore, by the more common occurrence of “divided government,” which has encouraged presidents to make more frequent use of unilateral administrative power in the service of partisan objectives.

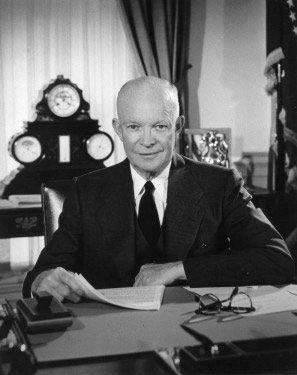

In 1954, President Eisenhower was able to expand Social Security with bipartisan support in Congress.

Of course, partisan polarization is not new. All major presidential reconstructions in American history have witnessed sharp party conflict; indeed, all of America’s most important reform presidents either founded or refounded a political party. Yet partisan warfare proved temporary in these transformative moments, befitting a party system that was exceptionally decentralized and ideologically flexible. As the new political order took shape, a strong, relatively bipartisan consensus formed in support of the reform program of the new majority party. For example, Dwight David Eisenhower, the first Republican president elected during the New Deal regime, bestowed bipartisan legitimacy on the liberal political order. Most significant, in 1954, with bipartisan cooperation, Eisenhower pushed through Congress an expansion of Social Security that extended its benefits to many parts of the society that the initial statute passed in 1935 did not cover, most notably occupations with large numbers of African-Americans and women.

But what was once episodic now seems routine. Contemporary Democrats and Republicans seem more intractably—structurally—divided. During the past four decades, a more centralized, programmatic, and polarized form of partisanship has emerged that appears to defy compromise, much less consensus. President Obama agreed to many concessions to his original health care legislation, including the sacrifice of its ambitious public option. But this acceptance of “market exchanges” failed to temper discontent on the right: the Affordable Care Act became the first major social welfare program to be enacted without a single Republican vote. Moreover, since it became law, the Republican majority in the House has voted more than 50 times to repeal what it calls “Obamacare,” and the whole 2016 Republican presidential field supports repeal as well.

A path forward

So what can a new president do in 2017 to negotiate the opportunities and hazards of the new party system? Recent history suggests efforts to transcend partisanship are quixotic. With Democrats and Republicans engaged in a fundamental partisan contest for the hearts and minds of a divided nation, artfully engaging rather than seeking to avoid partisan combat might better serve the new president.

Bernie Sanders speaks to a crowd in Madison, Wisconsin, while campaigning for the Democratic nomination for president.

More beholden to the Progressive tradition, recent Democratic presidents have been especially reluctant to assume the responsibility of party leadership. They have tended, as Skowronek observes, to substitute pragmatism for political doctrine—to sell themselves as leaders of the party of problem solving. The argument favored by recent Democratic presidents is that party confrontations are, as Obama suggested in words from Corinthians in his first inaugural address, merely “childish things.” Yet the view that major policies such as Obamacare are merely pragmatic responses to problems that transcend partisanship only rubs salt in the wounds of a Republican Party increasingly hostile to the progressive vision of social and economic justice. Indeed, the surge of Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders in the early rounds of the 2016 election campaign suggests that a new president’s claim that his or her administration serves “neutral competence” is likely to aggravate rather than assuage the causes of our present discontents.

These observations are not meant to suggest that the first year of the president should be consumed by partisan combat. One important task for the new president will be to make partisan debate less ad hominem—to focus partisanship on competing principles rather than personal recrimination. As Emory University political scientist Alan Abramowitz has noted, since the 1980s, there has been a growing trend of “negative partisanship,” where party differences are overwhelmingly expressed through mutual antipathy between Democrats and Republicans. These diatribes have focused especially on the occupant of the White House. The animating factor in mobilizing Democrats and activists during the Bush years was their hatred of the Republican president; by the same token, the animus for rabid GOP partisanship during Obama’s two terms has been contempt for the Democratic president.

Running for president, Donald Trump has tapped into voters’ anger about the state of politics and government.

“No matter who wins the Democratic and Republican nominations next year,” Abramowitz and coauthor Steven Webster wrote in a 2015 article for the University of Virginia Center on Politics, “we can expect anger at the opposing party’s candidate to run high, and we can expect both parties’ nominees to seek to tap into this anger in order to energize and mobilize their supporters. It promises to be a long and nasty campaign.” Likewise, if the recent past is prologue, the new president can expect the opposition party to keep its faithful engaged through personal invective directed at the White House.

Might the new president and his or her political allies benefit from making partisan politics less personal? Facing a similar task when the polarizing personality of Andrew Jackson entered the executive mansion, Martin Van Buren—the architect of America’s first party system—wrote to his comrade in arms, Virginian Thomas Ritchie, proposing that the great challenge in building a Democratic Party was to substitute “party principle” for “personal preference.” Although the modern executive office can never be separated from personal image and character, the new president’s rhetoric, staffing, and policy should be grounded in principles that explain the nature of the partisan contest that now consumes politics and governance in the United States. It might be a good thing, then, that both Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders have not merely embraced FDR’s “enlightened administration” by the executive branch, but also have returned to the principles Roosevelt enunciated in support of the liberal state. Reminiscent of FDR’s 1944 State of the Union address, which proposed a “second bill of rights,” Clinton and Sanders have argued that struggling men and women are not free men and women—that programs providing for greater security, such as adequate health care, are not a privilege but a right.

The acknowledgment of two leading Democratic candidates that partisan statesmanship involves, as Roosevelt claimed, “the redefinition of [constitutional] rights in terms of a changing and growing social order,” might be an important step toward a more meaningful national partisan debate—one that is more substantive and civil than the extant contest between pragmatism and conservatism. Similarly, Republicans should recognize that this defense of security as a new self-evident truth is not an alien idea but one that challenges them to engage in a struggle for the constitutional soul of the American people. Indeed, a large number of contemporary conservatives also believe that government must provide for the security of individual men and women. They have concluded that the national government has the responsibility to champion “family values” (a view which permeates proposals to restrict abortion and same-sex marriage), require work for welfare, impose performance standards on secondary and elementary schools, and protect the homeland—from terrorists and undocumented immigrants.

The current partisan contest, the next Republican president might thus acknowledge, is not truly about whether to expand or dismantle government. Instead, it involves the fresh, bracing question of what objectives the government should serve. Starting with the contest between Jefferson’s Republicans and Hamilton’s Federalists, the major chapters of the never-ending story of American democracy have centered on the meaning of our rights, and how these self-evident truths should be embodied by the Constitution. In this spirit, the next president, whether Republican or Democratic, should seek to infuse the framers’ words with new meaning, so that they fit the circumstances of contemporary American politics.

Such a shift from the personal to the collective will require a new president to display an exalted form of restraint. No presidential candidate should promise, as many have, to carry out major policy changes on Day 1 of their presidency. Nor should any new president, sidestepping Congress, move quickly to pursue his or her agenda through unilateral executive action. Such a presidency-centered democracy risks embroiling presidents in policy controversies that diminish collaboration with Congress, roil the system of checks and balances, and erode citizens’ trust in the competence and fairness of the national government. Paradoxically, our present discontents might call for reconciling a more visionary leadership and purposeful partisan administration with presidential patience and acts of forbearance.