If I were to advise the next president on inauguration eve, I would remind him or her that the oath they will take the following midday will start an implacable four year countdown. But I would also point out that the calendar is only one measure of time for the nation’s political leader. The critical question at the commencement of any new presidency is “what time is it?” The answer is seldom transparent.

“What time is it?” is an especially hard question for presidents of the modern era. The organization of American government and politics is increasingly complex, and its various aspects run on different clocks. One clock keeps “secular time.” It marks the inexorable thickening of the institutional universe of political action, the widening array of stakeholders in government policy, and the press of ever more complicated problems for government to solve. Secular time casts the president as a hands-on manager of the government’s sprawling commitments, as the master orchestrator of promised services and competing demands, as the responsible steward of a policy state. In secular time, performance is about finding solutions that work.

President Ronald Reagan and Vice President George H.W. Bush wave to the crowd at the Republican National Convention in 1984. Reagan was the last president to successfully reset political time while George H.W. Bush focused on responsible management.

Another clock keeps “political time.” Political time measures the years that unfold between periodic resets of the nation’s ideological trajectory. It tells of the state of the political movements contesting national power, of the expectations of the mobilized polity. Those operating on political time see the president as an agent of change poised to break through the knot of interests and institutions that block concerted action on the agenda he or she was chosen to champion. They anticipate a populist intervention, a purge of the entrenched, a thoroughgoing reconstruction of governmental operations. Performance in political time is about reconfiguring government to conform to a particular political ideal or reform principle.

Nothing in recent years has so tested the political skills of incumbents as striking a sustainable balance between these two competing frameworks for presidential action. Consider Ronald Reagan, the last president to successfully reset political time. The Revolution of 1981 thrust a conservative insurgency into control of the national agenda, and Reagan’s first budget followed up with a programmatic breakthrough designed to lock in movement priorities. In the implementing it, however, he sent the nation into an economic tailspin. It was just the opposite for Reagan’s successor, George H. W. Bush. Though an affiliate of the Reagan Revolution, Bush chose to elevate the values of responsible management over movement priorities. But when he orchestrated an ecumenical budget compromise addressed to the nation’s economic problems through a balanced scheme of tax increases and spending cuts, he drew the wrath of the conservative insurgency, sending his presidency into a political tailspin.

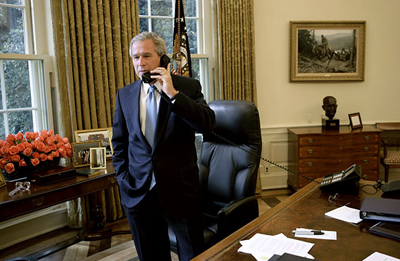

So what time is it now? Since Reagan reset the political clock three and a half decades ago, we have had two iterations of affiliated leadership. Like Bush 41, Bush 43 had to wrestle with the dilemmas of upholding conservative orthodoxy while trying to respond to the relentless press of new demands for responsible management and problem solving. He avoided his father’s misstep on taxes with cuts that appealed to his political base, but other initiatives—on education, prescription drug provision, and emergency response to the financial crisis—confounded the expectations of movement conservatives and stiffened their confrontational stance.

We have also had two iterations of opposition leadership. Bill Clinton and Barack Obama failed to dislodge the conservative project, but they did expose the vulnerabilities of conservative orthodoxy and exploit its difficulties in coming up with responsive new solutions to the problems of the day. Clinton disavowed orthodoxies on the right and the left alike. He goaded both sides with a policy strategy of “triangulation” and achieved enormous popularity with the political attractions of his “Third Way.” Obama was more aggressive. He promised to “change the trajectory” of national affairs and do for progressives what Reagan had done for conservatives, but he promised to do it in an ecumenical way, one that acknowledged the full range of interests in national action. His signature initiative, the Affordable Care Act, pulled his followers in the progressive movement kicking and screaming behind an initiative that reached out to all the stakeholders in the health care industry. Still, implementation proved a management nightmare, and the movement mobilization was all on the other side.

Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama are examples of opposition leadership. They failed to upend the conservative movement but exposed vulnerabilities and came up with new solutions.

The political sequence as it has unfolded since 1981 fits well-known historical patterns. Think for example of the rise and fall of Jacksonian Democracy between 1830 and 1860, or the rise and fall of New Deal liberalism between 1930 and 1980, each of which followed a similar rotation of alternating victories for the party that carried forward the received political orthodoxy and the party at odds with it. Nonetheless, from its inception under Ronald Reagan, the current sequence has also been marked by widening disparities between the demands of political and secular time. This growing dissonance will complicate the next move whether the new president is a Republican or a Democrat. The complications posed, however, would be a bit different in each instance.

If the election of 2016 follows the patterns of the past in lockstep, we would expect the inauguration of a Republican president in 2017 and with that, a third iteration of orthodox innovation. I would advise that new president to consider carefully the plight of presidents in this circumstance in earlier sequences. This is not advice the incumbent will want to hear, for Franklin Pierce and Jimmy Carter come quickly to mind as the parallel historical cases.

Each of them was the third affiliate of a now-distant reconstruction of political priorities, and each led a party that was straining ideologically to remain abreast of the times. Pierce won the presidency on a pledge that he would take no further action with regard to slavery, the very issue that was tearing his party and the nation apart. Carter won in a campaign in which he cast a wary eye over his party’s liberal agenda. There were, he advised, “no easy answers” to the questions facing the nation. In both cases, the mobilized elements of the coalition the president represented were pressing more extreme and controversial demands on government, demands that threatened the new incumbent’s standing as a responsible steward of national affairs. Each of these presidents opted for a different way out of their shared dilemma, but immediately upon assuming office, both threw the old order into an existential crisis. Pierce broke his pledge on slavery, reached out to his party’s stalwarts, and pushed through the controversial Kansas-Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and let new states decide for themselves whether to allow slavery. This choice provided the opposition proof certain that the old order was bankrupt of responsible solutions to the problems of the day, and it ultimately led Pierce’s own party to drop him as a political liability. Carter, on the other hand, stiffened his resistance to his party’s orthodoxy, even to the point of reversing the Democrats’ traditional formula for economic management and privileging the fight against inflation over the commitment to full employment. The charges of betrayal from within the president’s own ranks fueled a dump-Carter movement, leaving the president politically weakened in the face of the rising conservative insurgency.

President George W. Bush gives his State of the Union address in 2006, when Republicans controlled the presidency and both houses of Congress. When one political party controls both branches of government, it creates pressure on the president to implement the party’s vision.

For a Republican president in 2017, this dilemma is likely to be particularly acute. A Republican presidential victory next year will almost certainly confirm Republican control of the Congress, and with an extraordinary degree of homogeneity of opinion within the party caucus, the pressure to seize the moment, rout the opposition, and secure the vision will be intense. Presidential resistance to partisan follow through would surely foment a political implosion, but presidential indulgence of long pent up demands—to repeal health care reform, for instance, or to move decisively against undocumented immigrants, or to reverse direction on climate change—will just as surely tempt a political counterrevolution. There are no good choices here, but my advice would be to risk the implosion and adopt secular time as the guide.

The difference between Pierce and Carter is instructive here. Pierce chose to stand with his party’s stalwarts and quickly found himself marginalized and discarded by them as damaged goods; Carter resisted his party’s stalwarts, took his stand as a steady manager of national affairs, and defeated their challenge to his renomination. Carter deployed the expanded institutional resources of the modern presidency to project a national political persona that was sui generis, indifferent to the ideological alternatives contending for the passions of the electorate. He used the president’s enhanced position in secular time to elevate the managerial ideal and its promise of responsible stewardship. It was a gamble he ultimately lost, but it was also a bet on the future. For a president desperate to escape the dismal cycles of political time, the opportunities opened by secular time beam brightly.

President Jimmy Carter promoted the managerial ideal of the presidency and focused on responsible stewardship of the government.

But what about a Democratic victor in 2017? Historically speaking, that is the more interesting prospect, for we do not have good examples of presidents like Barack Obama—an oppositional leader in a still resilient regime—passing power onto a member of his own party. The presidents who have done so—Thomas Jefferson, Andrew Jackson, Franklin Roosevelt and Ronald Reagan—were opposition leaders who successfully reset political time by reconstructing the government’s priorities and establishing a new orthodoxy. That was something Obama aspired to do but failed to accomplish, the shortfall evident in the 2014 midterms, if not earlier in the Tea Party insurgency of 2010. The pattern of two-elected-terms-and-the-opposition-party-is-out was almost broken in 2000 when Al Gore nearly succeeded Bill Clinton, and the temporal proximity of that lone example might suggest a widening range of political possibilities. Nonetheless, a Democratic successor to Obama would be an anomaly in political time.

Two pertinent historical patterns help bring this curious situation into sharper relief. First is that, with each new iteration of a presidency opposed to reigning political orthodoxy, the mobilizing energy behind its critique of those priorities strengthens and expectations of a political breakthrough are heightened. Consider the sequence of Grover Cleveland, Woodrow Wilson and Franklin Roosevelt: each successive Democrat delivered a more direct and potent punch to the Republican orthodoxy of the period. The sequence of Dwight Eisenhower, Richard Nixon, and Ronald Reagan follows the same pattern: each more forcefully challenged the New Deal orthodoxy before Reagan reset the clock. A comparison of the relatively restrained Clinton to the more-aggressive Obama fits that pattern, suggesting that a third iteration of Democratic leadership against the reigning conservative orthodoxy harbors the potential for a decisive breakthrough and reordering.

The advent of the Great Depression during the administration of Herbert Hoover energized Franklin Roosevelt to take decisive action.

But the second pattern to consider cuts the other way: it reminds us that that these breakthrough moments were always immediately proceeded by a disgraced exemplar of the old regime’s incompetence, never by a fellow opposition leader. The decisive breakthrough under Franklin Roosevelt was more directly energized by the implosion of the Hoover administration than by the foreshadowing of Wilson; the decisive breakthrough under Reagan was energized more directly by the implosion of the Carter administration than by the foreshadowing of Nixon. It is hard to imagine a political reconstruction without the prior political implosion.

A Democrat in 2017 would, then, be dealing with a conspicuous wrinkle in political time. Movement supporters will be mobilized and expectant, more insistent than ever on a decisive reordering, but there will be no conspicuous failure of national leadership against which to position a sharp break or clear alternative. Moreover, the incumbent will likely be dealt a continuation of divided government. The president’s most faithful followers would be looking finally to reset the clock, even as the election would, in effect, ratify the status quo.

The first bit of advice I would give this president is just to consider the uniqueness of this moment. The unprecedented character of such a victory is a sign of the waning of the traditional rhythms and tropes of political time, their recession as dominant factors organizing American politics. It is as well an indication of the rising influence of the managerial ethos of secular time, where problem solving and policy orchestration trump transformative visions and populist interventions.

President George W. Bush was successful in motivating his supporters by focusing on beliefs as opposed to pragmatism as a mobilizing standard.

But I would quickly follow up with a cautious appraisal of these prospects, for to rest content with this reading of the moment is certain to keep this president on the political defensive. The goods and services of the policy state are scattered and particular; constraints—political, institutional, and economic—weigh heavily on every promise to extend their range and effectiveness. If presidential leadership offers nothing more than an affirmation of the operations of the policy state, if its promise is just to improvise solutions that might work, if it sets its sights pragmatically on satisfying stakeholder demands, support is unlikely to remain mobilized for long, and more importantly, those possessed of a principled belief that government cannot be the solution to our problems will retain an easy target. The conservative insurgency has sustained itself through successive defeats and come back strong by exploiting the weaknesses of pragmatism and problem solving as a mobilizing standard.

If the ambition of a Democratic administration in 2017 is to build momentum for something different and durable, he or she will need to do more. The president will have to find a way—how is not currently clear—to rearrange the political landscape in a way that compels some level of deference even from implacable opponents. Nothing will be more important (or challenging) in this regard than articulating a project for the nation as a whole and setting presidential action in a historical narrative that looks beyond problem solving for political motivation. Put another way, so long as the Democratic alternative is just more of the same, prospects for a displacement of the conservative insurgency will remain dim. Democratic leaders content to claim issue victories catch-as-catch-can play to the strengths of their opponents, for no American will remain content to live in times like that indefinitely.