The different ways in which presidents enter the White House often shape their first-year prospects and agendas. Accidental presidents like Theodore Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson typically feel obliged to assure the American people that they will seek to continue the work of their untimely departed predecessors. Presidents who win election by virtue of the continuing popularity of living predecessors—William Howard Taft and George H. W. Bush, for instance—experience similar pressure.

Presidents who enter office with decisive popular mandates—Warren Harding, Franklin Roosevelt, Dwight Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan—enjoy unusual credibility. Presidents who are greeted by friendly Congresses—Woodrow Wilson, Warren Harding, Franklin Roosevelt, and Lyndon Johnson—have a head start on their policy agendas.

Finally, former governors—Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Calvin Coolidge, Franklin Roosevelt, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush—have executive experience not possessed by former members of Congress, who nonetheless compensate by having greater knowledge of the legislative process.

Differences aside, first-year presidents face similar tasks, of which three stand out. First, they must form administrations. In particular, they must select cabinet secretaries and individuals to fill the many other top positions in the executive branch. Second, they must articulate and initiate domestic policy agendas. That is, they must tell Congress and the American people what they want to accomplish, and they must take first steps toward achieving their goals. Third, they must establish their leadership of the foreign-policy apparatus. Since 1945 the United States has played the predominant role in world affairs; other governments and peoples scrutinize new presidents to assess how this predominance will be exercised. No less do the American people examine the foreign-policy talents and aspirations of new presidents.

President Ronald Reagan meets with his advisors, including (from left to right) Ed Meese, Michael Deaver, James Baker, and James Brady.

History suggests that first-year presidents should keep several considerations in mind as they take up these tasks. In selecting individuals for their administrations, presidents should balance their personal connections to appointees with appointees’ experience of government. This is especially important for presidents with little personal experience of their own of life in Washington. Carter’s reputation as an outsider served him well as a candidate in the wake of the Watergate scandal, but the “Georgia mafia” that took control of the White House found Washington unfamiliar and, soon enough, unfriendly. Carter’s presidency suffered as a consequence. Reagan, by contrast, created a “troika” consisting of two loyalists from California, Michael Deaver and Ed Meese, and Washington pro James Baker. Reagan’s administration got off to a fast start and continued to run smoothly with Baker as chief of staff. (Things unraveled under Baker’s successor, Donald Regan.)

Incoming presidents must establish priorities. Some presidents have priorities thrust upon them: Lincoln had to deal with secession, Franklin Roosevelt to address the Great Depression, Truman to finish World War II. But most presidents have leeway in deciding what to tackle first. Even amid the crisis of the Depression, Roosevelt initially focused on rescuing the banking system and getting relief to unemployed workers and their families; measures with longer horizons, such as Social Security, were deferred till later. Lyndon Johnson had big plans for his Great Society, but his first year was given to civil rights reform. Reagan devoted his first six months to cutting taxes and nondefense spending. Presidents without focus, by contrast, have often failed. The micromanaging Carter wanted to be everywhere but, as a result, spread himself too thin to gain policy traction anywhere. Clinton ran on economic issues (“It’s the economy, stupid”), but wandered afield into a disastrous effort to reform health care.

First-year presidents must confirm their connection to the American people. Accidental presidents might have to do this for the first time. Most Americans knew little about Theodore Roosevelt beyond his service in the Spanish-American War. They knew that Coolidge disapproved of strikes by the police (“There is no right to strike against the public safety by anybody, anywhere, any time”). They knew Truman wasn’t FDR’s first choice for vice president (nor his second). They knew Lyndon Johnson was from Texas. But elected first-termers have no less need to strengthen their connection with the people. Since Andrew Jackson’s 1828 election, the presidency has been peculiarly the office of the people. No other elected official is answerable so directly to the people of the nation at large. The most influential presidents have derived their power from the people. Lincoln embodied the national will (which was to say, the Northern will) during the Civil War. FDR employed radio to forge a link with the American people during the darkest months of the Depression; the people responded by roundly endorsing the New Deal and resoundingly reelecting Roosevelt. Reagan was to television what Roosevelt had been to radio; Reagan’s televised speeches aroused public sentiment against Democratic House Speaker Tip O’Neill and other opponents of the president’s 1981 tax and spending plans.

When Theodore Roosevelt became president in 1901 after President McKinley’s assassination, most Americans knew little about him beyond his service in the Spanish-American War.

Here again, the failures are exemplary. Herbert Hoover lost touch with the American people amid the stock market crash of 1929 and never regained it. Gerald Ford, already burdened with his lack of election to the presidency, undermined his credibility by pardoning Richard Nixon for his Watergate offenses. Barack Obama sailed to victory in 2008 on a platform of hope, but as president he failed to maintain the emotional connection that had made him so compelling to voters. Even his supporters, galvanized by the campaign promise “Yes, we can,” grew tired of hearing that no, they couldn’t.

Elected first-termers must recognize the difference between being a candidate for president and actually being president. The secret of the successful candidacy is the raising of expectations (the Obama campaign trademarked “Yes, we can,” but the concept is as old as elective politics itself), whereas a secret of successful presidencies is the management of lowered expectations (the no-you-can’t part of the equation). Successful presidents, typically invoking priorities, artfully escape the less realistic promises they made when candidates. Franklin Roosevelt as a candidate pledged to balance the federal budget, but as president, citing the great needs of the Depression-ravaged country, he never came close. Less artful presidents suffer the consequences. George H. W. Bush egregiously promised not to raise taxes (“Read my lips: no new taxes”); when soaring deficits and Wall Street’s consequent alarm impelled him to accept tax increases as the price of Democrats’ agreement to trim spending, he was pilloried and mocked (“Read my lips: I lied”), and then defeated for reelection.

If rigid attachment to campaign promises is a first casualty in a successful presidency, a second is devotion to principles that, while laudable in individuals, are dangerous to presidents. Friends ought to be loyal to friends, but presidents should be loyal only to the national interest. Andrew Jackson refused to fire his secretary of war, John Eaton, a man who had devoted years of his life to the service of Old Hickory. But Eaton’s wife, Peggy, had a checkered background that scandalized the wives of the members of Jackson’s cabinet, who not unnaturally placed the feelings of their spouses above those of Peg Eaton. The kerfuffle paralyzed the administration for months. Jackson should have told Eaton to resign, but he was too loyal to his old friend. The nation suffered. Franklin Roosevelt understood what Jackson did not. Roosevelt’s path to the White House had been smoothed by Louis Howe, who stood by FDR during the years when Roosevelt, afflicted by adult-onset polio, couldn’t stand on his own. But upon election, FDR recognized that Howe was no longer useful. Gently but firmly Roosevelt pushed Howe aside and proceeded with the nation’s business.

First-year presidents must develop a working relationship with the leaders of Congress. This is comparatively easy, though not assured, when those leaders are members of the president’s party and share the president’s views. It is harder, but more necessary, when Congress is controlled by the other party or by dissenting members of the president’s own party. Republican Dwight Eisenhower (birthplace: Denison, Texas) cultivated Texas Democrats Lyndon Johnson, the Senate majority leader, and Sam Rayburn, the Speaker of the House of Representatives.

Johnson as president, facing opposition to civil rights reform from conservative Southern Democrats, successfully appealed to Everett Dirksen, the Republican Senate minority leader, to help him muster the votes reform required.

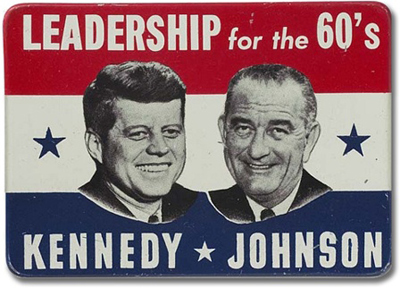

John Kennedy offered Lyndon Johnson of Texas the spot of vice president to try to entice Southerners to vote for the Democratic ticket and to make Johnson part of the team.

Presidents should profess belief in the sincerity and good intentions of powerful legislators, even when they have to lie through their teeth in doing so. Thomas Jefferson waved the olive branch after the ugly election of 1800; the first Republican president declared, “We are all Republicans; we are all Federalists.” Jefferson didn’t mean it, and no one believed it. But the gesture was graceful and might have kept some congressional Federalists from cutting off their noses to spite their faces when Jefferson asked for their support in the purchase of Louisiana. Reagan let on that he and O’Neill shared an Irish bonhomie that came out over drinks at the end of long days battling over the budget. In reality it was an act (performed by the only president to enter the White House via Hollywood). Reagan distrusted O’Neill and bitterly complained in private that the Speaker placed personal and partisan interests above the interests of the country.

One way of dealing with rivals and malcontents is to bring them into the administration. Lincoln gave William Seward, the original front-runner for the 1860 Republican nomination, the senior cabinet post, as secretary of state. Franklin Roosevelt made John Nance Garner, a conservative skeptic of Roosevelt’s welfare state policies, vice president. John Kennedy offered Lyndon Johnson the vice presidency, hoping the offer would impress Johnson’s fellow Texans enough to keep them from voting Republican. Johnson may or may not have surprised JFK by accepting the offer, but the indisputable result was the elimination of Johnson as a rival for Democratic supremacy in Washington. Barack Obama vanquished Hillary Clinton in the 2008 primaries, and made her secretary of state.

First-year presidents should approach foreign affairs with caution. Seldom do candidates get elected for reasons of foreign policy. Voters are almost always more interested in domestic affairs, particularly those connected to the economy, than in international affairs. For this reason, there is little to be gained by rushing to decide large matters of foreign policy. And there is much to be lost. New presidents quickly discover that international context determines most of what presidents do in foreign policy, and that campaign promises become dead letters about the time presidents-elect receive their first classified briefings. Kennedy raked Eisenhower for the “missile gap” Ike had let develop between the United States and the Soviet Union; upon election JFK was informed that there was indeed a missile gap but that it favored the United States. Carter, the first president elected after the American defeat in Vietnam, promised a foreign policy that allowed room for the revolutionary ferment in the developing world, but after the fall of American allies in Nicaragua and Iran, and after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, he proclaimed a personal epiphany, issued the sternest presidential doctrine of the Cold War (against Soviet approach to the Persian Gulf), and launched the great arms buildup for which Ronald Reagan received credit. Candidate Barack Obama campaigned to close the American prison at Guantanamo Bay; when he couldn’t figure out what to do with the inmates, he left the prison in place.

President Woodrow Wilson announces to Congress the end of diplomatic relations with Germany in 1917. Although Wilson was elected on a domestic platform, he spent much of his presidency focused on foreign affairs.

A positive example of circumspection in foreign affairs is that of George H. W. Bush. Despite being elected as a proxy for a Reagan third term, Bush spent the first months of his administration conspicuously rethinking Reagan’s policy toward the Soviet Union. The hiatus allowed Bush to gauge the growing resistance to communism in the Soviet belt of Eastern Europe and to formulate policies that helped guide Europe and the world to a soft landing after the Soviet engines of the Cold War flamed out.

Another reason for circumspection is that the unruly world repeatedly takes American presidents by surprise. Woodrow Wilson was elected on a domestic platform in 1912; as he prepared to take his inaugural oath, he told an associate that it would be an “irony of fate” if foreign affairs figured largely in his presidency. A year and a half later, the largest war in history till then broke, eventually engulfing Wilson’s presidency. George W. Bush expected to be a domestic president until the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, pushed policy toward the Middle East to the top of his agenda.

First-year presidents should think small, rather than large. Truly transformative presidencies are rare, because the American status quo resists change. This is partly because entrenched interests and practices are stubborn, but also because the status quo has served America well these past two centuries. Americans don’t like to fix what isn’t broken. On those very unusual occasions when things are broken—the Civil War, the Great Depression—Americans allow presidents to rise to greatness. It is no coincidence that the two greatest presidents (not named Washington)—Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt—presided over the two worst periods in American history.

Presidents who have pushed too hard against the status quo have very often been frustrated. Wilson tried to lead America into a world government; the Senate slapped him down by rejecting the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations. Clinton sought universal health care; Republican avatars “Harry and Louise” contended that things were OK the way they were, and Americans agreed.

A better model for incoming presidents is Theodore Roosevelt. The Rough Rider lacked neither imagination nor ambition, but he contented himself with reforming the status quo rather than overturning it. Roosevelt’s success in busting trusts, regulating railroads, ensuring the safety of America’s food and drug supply, protecting women and children from the perils of industrial labor, preserving America’s wild beauty and conserving the country’s natural resources won him a spot in the presidential pantheon just below the triumvirate of Washington, Lincoln and FDR. Absent undeniable national emergency, TR’s record is about the best a president can hope for. To aim for more is to risk—likely guarantee—achieving little or nothing at all.

First-year presidents who heed the foregoing advice are by no means assured of success. The presidency is a daunting job, with competing and contradictory demands that no president, however gifted, can entirely satisfy. The most popular candidate will be harshly criticized as president, often sooner rather than later. Yet faint hearts don’t seek the White House, and new presidents always take up their task with big plans and high hopes. It is well that this is the case, for ambition and self-confidence are essential qualities in persons undertaking large endeavors of any kind. But so is attention to what has gone before, and first-year presidents who study their predecessors will increase their chances of becoming second-term presidents.