What must the next president do in the first year to manage the overheated, ubiquitous, yet fragmented media environment in which we find ourselves today?

Facebook. Instagram. Snapchat. Twitter. Multiple 24/7 cable channels and continually updated online news sites. All of these media platforms offer opportunities and create perils. The next president can connect more directly and quickly with the electorate than ever before, but will also be placed under more intense and relentless scrutiny.

Today’s media are not primarily controlled by top-down, one-to-many modes of communication: Now anyone with a cell phone can record and circulate what a president or presidential candidate says—something Mitt Romney discovered to his dismay. The face a president wants to present to the public—his or her front-stage persona—can be exposed as fraudulent when comments or images from unguarded moments—the backstage persona— contradict a carefully crafted public image. E-mail, Twitter feeds, and websites can be hacked to reveal such backstage moments. And the multiplication of media platforms has allowed for the rise of avowedly partisan cable channels and websites, stoking political animus in the country that amplifies both praise for and criticism of the president.

In the 2012 presidential election, Mitt Romney learned the hard way that anyone with a cellphone can record and circulate what a presidential candidate says.

The next president will face an unprecedented challenge in navigating—and trying to harness—the multiple media outlets available. So it can seem that there are no lessons from the past that might help the new president manage this unruly media environment. Yet since the late 19th Century, most presidents upon taking office have found themselves in new, seemingly unpredictable media environments, ones that had the potential to enhance their ability to advance their policies and bolster their public approval or, alternatively, to thwart their efforts. Thus, presidents and their staffs have had to have a keen appreciation of what academics call the particular “affordances” of new media platforms and communications technologies—their inherent properties that favor and even require certain kinds of communication strategies and public performances over others.

Affordances are the possible uses we can and cannot make of a particular medium. For example, radio denied sight to its audience and thus words, music, and sound effects had to carry all the weight to enable listeners to “see” with the mind’s eye. This was what Franklin Roosevelt had to come to terms with when he assumed office. For John F. Kennedy, it was the visuality of television. For George H. W. Bush and Bill Clinton, it was the rise of cable news and the overheated 24/7 news cycle. And for Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Donald Trump, it has been the speed, immediacy, and many-to-many networks of the Internet and social media and their interplay with traditional media outlets.

What have been the effects of all this for the presidency? Each of these technologies has reduced the distance between the president and everyday Americans. This increased access has allowed Americans to judge presidents on a much more personal level. Does he seem sincere? Does she convey authority and knowledge? Is he telling the truth? By hearing the president’s voice on the radio and, later, seeing him on television, many Americans developed “para-social relations” with him: responding to his media performances as if he were a personal acquaintance who was with them in a face-to-face social relationship.

So presidents have had to come to terms with this heightened intimacy, evolve their news management strategies and approaches, and craft a public persona that appears authoritative, genuine, and relatable. The characteristics Americans have responded to most positively are a blend of policy expertise and personal authenticity. This requires increased discipline and an acceptance of increased transparency. Given the enormous distrust of government right now, and widespread frustration across the political spectrum that we seem to have a government by and for elites, a sense of transparency and a genuine concern for all Americans as conveyed through the media will be absolutely crucial to the next president’s success. Despite the digital revolution, media fragmentation, and the rapid-fire news cycle, the past still offers valuable communications lessons for the next president’s first year.

Understand the various media at your disposal, the advantages of each, and the differences between them. Be disciplined and prepared in using these media.

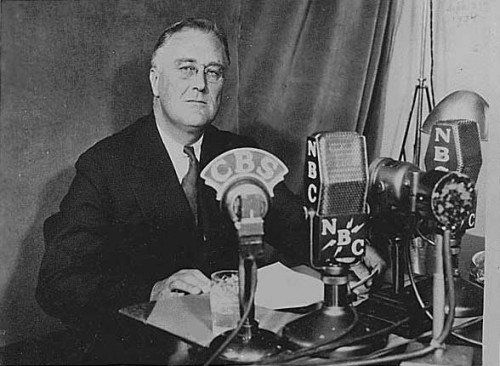

Franklin Roosevelt, unlike his predecessor Herbert Hoover, understood what radio afforded him—the intimacy of his voice penetrating each American home and seeming to speak, simultaneously, to each individual. Indeed, you can’t say Roosevelt’s name without immediately thinking “fireside chats,” so effective was FDR’s command of the relatively new technology. Roosevelt deliberately imagined his audience as a few people sitting around his fireplace with him; he did not use the stentorian political oratory of the stump, but rather the intimate “I-you” mode of address. He opened the chats with “My friends,” and was careful to use simple, direct, informal language. While each chat indeed sounded relaxed and unrehearsed, each was the result of extensive preparation and multiple drafts. Having discovered that a separation between his two front lower teeth produced a slight whistle on the air, he had a removable bridge made that eliminated the sound. That’s called paying attention to the advantages and requirements of a particular medium!

President Franklin Roosevelt introduced “fireside chats,” taking advantage of the new technology of radio to build a bond between himself and the American people.

While it is fair to say that Dwight Eisenhower was the first television president (he was the first to have televised “fireside chats,” and introduced the televised news conference in 1955), it was Kennedy and, later, Ronald Reagan, who truly mastered the visual (and increasingly live) possibilities of the medium. Both men understood the importance of visual symbolism and a commanding stage presence. Kennedy’s use of the live press conference, often peppered with spontaneous jokes and witticisms, all helped by his handsome and youthful appearance, made him seem authoritative and spontaneous—someone genuine. Reagan, the seasoned actor, also appreciated the importance of off-the-cuff humor on live TV, the symbolism of his cowboy hat, and how to use visual props—for example, thick sheaves of former regulations he was replacing with just several pages of new ones—to sell his programs.

By 2000, a new medium was in its nascent stage: the Internet. By the time Barack Obama ran for president in 2008, 68 million Americans had broadband connections. With the explosion in the Internet’s reach, and the new possibilities of social media like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and texting, presidents and presidential candidates were once again confronting an emerging, transitioning media environment while still also having to master traditional media, especially television.

Campaigns and presidents can now communicate directly to the electorate with no filter, circumventing traditional gatekeepers. But increasing numbers of people are using Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to post political information, both factual and false, over which presidents have no control. Social media, and especially Twitter in 2016, led to mainstream media attention, often driving the news cycle. And Twitter, with its 140-character limit and, for some, anonymity, promotes short, simple, dramatic posts that have led to linguistic bombast, dueling, and even aggression, especially against women. The pitfall for a president is to overuse Twitter, e-mail, and Facebook, leading to overexposure and a possible loss of credibility. With the ubiquity and ceaseless introduction of new apps, the new president will need both young people (the so-called “digital natives”) and seasoned pros to work together to grasp the benefits of each platform and to navigate this treacherous and fragmented terrain.

Presidents can more easily communicate directly with the people on social media such as Twitter but presidents need to be careful not to overuse them and risk overexposure and a loss of credibility.

Appreciate how your “presentation of self” can be shaped by new media and understand how to deal with the ongoing erosion of presidential privacy.

With the 24/7 news cycle and the ongoing surveillance of presidents through traditional and social media, cultivate your front-stage persona and protect your backstage, but let people see enough of your backstage to relate to you. The explosive growth of celebrity journalism in the 21st Century and its “they’re just like us” paparazzi shots has increased the public’s appetite for more seemingly unguarded, candid moments of famous people to gauge their authenticity. John Kennedy’s carefully staged shots of his children playing in the Oval Office, and the multiple photos and videos of Barack Obama joyfully engaging with children, conveyed tenderheartedness, a sense of fun, and a genuine connection to humanity. But the media, traditional and digital, relish discovering unguarded moments—Gerald Ford tripping, Jimmy Carter collapsing while jogging—so protecting one’s backstage, while providing some access to it, is an increasingly tricky proposition. And in this age of hacking and cyberattacks, the president will need to secure how he or she communicates with others in the administration.

President Obama's moments joyfully engaging with children convey tenderheartedness, a sense of fun, and a genuine connection to humanity.

Accommodate the journalistic needs, routines, and practices of the major news organizations. Despite everything, they still matter.

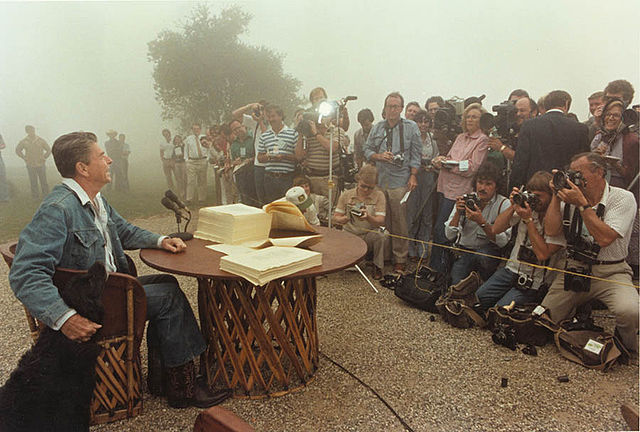

Beginning with George Washington, many presidents have hated the press, and trust in the news media today is low. But an informed public is crucial to democracy and the truth is that those who accommodate journalists’ needs get better coverage. Ronald Reagan’s team tended to the “care and feeding” of the press, providing them with the president’s daily schedule and press releases, giving them summaries or full copies of his speeches or comments in advance, and adhering to the “message of the day.” Thus, they did much of the journalists’ work for them, making their jobs easier. They understood that sound bites for presidents were getting ever shorter and that imagery mattered, so they planned the photo opportunities in advance so the optics would be positive and reinforce the message. Reagan’s aides used carefully orchestrated leaks to shape foreign policy and its coverage. As a result of all this, he enjoyed a much longer honeymoon than other presidents.

During President Reagan's administration, his team worked hard to make it easier for the press to do their jobs and carefully orchestrated media events.

Bill Clinton and his staff, by contrast, infuriated many reporters. One of the administration’s first blunders was challenging the geography and traditions of the White House pressroom. This room is cramped, with reporters jammed in cheek by jowl, and it is connected by a narrow hallway to the White House briefing room. Before or after briefings, reporters could also go to the “upper press office,” where the press secretary was located. George Stephanopoulos cut off this access, producing an outcry. Reporters complained that briefings were late, often by hours, that some interviews were cancelled, and that Clinton’s team failed to return phone calls. Thus, despite Clinton’s considerable personal skills as a communicator, his administration’s unskilled media apparatus gave him one of the shortest presidential honeymoons in recent history.

The news media do get savvy to news management strategies, especially if they become obvious, so too much stagecraft is a mistake. But with a few exceptions, news outlets today have been defunded and operate with fewer resources, and to the dismay of many journalists themselves, rely on conflict, sensationalism, and the superficial over the substantive. A president and a staff who work with this state of affairs, present policy proposals in simple, telegraphic terms, and provide the news media with the tools and information to do their jobs will fare much better than an administration that does not.

Never use the media to stage events or promote positions that are at odds with actual policy. Allow no gaps between presidential pronouncements and the reality of what’s occurring.

The most infamous recent example of this mistake was George W. Bush’s “top gun” landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003 to announce the end of major combat in Iraq. Every aspect of the event was choreographed, especially the now infamous “Mission Accomplished” banner strung across the ship. Bush himself arrived wearing an olive-green flight suit with a helmet tucked under his arm, having allegedly copiloted a Navy jet onto the ship’s deck. But after the initial dazzle over the event, journalists noted that the mission had not been accomplished at all; U.S. troops were still in Iraq and would end up being there for years. Also revealed was that there had been no need for Bush to fly in on a jet. You could see San Diego from the USS Abraham Lincoln; Bush could have come out on a motorboat or helicopter.

George W. Bush's landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln in May 2003 was an infamous example of staging events that are at odds with actual policy.

In his second term, the gap between how Bush handled the 2005 catastrophe of Hurricane Katrina and what television cameras were showing to the American people further undermined his credibility. The disaster illustrated that even under the most disciplined media strategies— which characterized the Bush administration for years—if you don’t get out ahead of the news, and if there is a gap between presidential performance and presidential imagery, the media will expose it.

So yes, “news management” is both a dirty word and suspect practice, but it is central to presidential success. With distrust of so many institutions at historic highs, Americans need a president with policy expertise who also conveys authenticity and is not defensive. Be honest and be yourself and don’t stonewall. All of this is more daunting in the current media environment. And it will be especially important and challenging for a woman, who will need discipline, compassion, and a very thick skin, given that the news media remain a male-dominated institution.

At this historic juncture, with an unprecedented array of communication tools at the disposal of the president, he or she must carefully manage these media and their opportunities while, at the same time, offering a genuine, unscripted persona obsessed not with image management but moving the country forward.