Since the landmark opening sessions of Franklin Roosevelt’s first term, presidents and the news media have touted the first hundred days of a new administration as a precious window during which ambitious goals might be achieved or forsaken. That early record is even said to foretell the overall fortunes of an entire presidency.

It’s easy to see why. A rookie president, entering office with as much goodwill as he (or she) is ever likely to enjoy, has room to maneuver and opportunities to act that seldom last long. At least since FDR, moreover, presidents have intently followed the media’s short-term judgments about success and failure—leading to overweening attention to favorability ratings, the tenor of insider opinion, and whether the president had “a good week.” Moved by such concerns, presidents and their staffs have bought into the hundred days mythology, working hard to ensure positive headlines when the deadline comes around.

But presidents and their staffs would be wise to pay a bit less attention to the hype about the first hundred days. Historically, that arbitrary benchmark has rarely correlated with the subsequent success or failure of a president’s time in office. All modern presidents go through ups and downs, periods of positive and negative coverage, none of which matter much in the long run. Above all, it’s a myth that presidents can succeed through good public relations. On the contrary, those presidents whom we recall as skilled communicators are typically remembered that way only because they actually accomplished things. A reputation for facility with communication follows from a record of achievement, not the other way around.

Given all this, it is time for presidents and their aides to stop trying to amass a list of accomplishments that can be rolled out for the news media at the start of May. Instead, they should prioritize key, substantial issues. In particular, successful presidencies—even those with rocky launches—have begun with the passage of a major economic plan that can both set the ideological tenor of an administration and, if it spurs recovery and growth, create space both politically and fiscally to achieve other goals in subsequent years.

To be sure, the hundred days mythology will die hard. The term has a long history. It originally came not from Roosevelt’s time but from Napoleon’s (les cent jours). In 1815, the exiled conqueror escaped from his redoubt on the island of Elba, rallied the French army, and briefly restored his rule until his defeat at Waterloo. Technically, all of this took 111 days to unfold, but the period came to be called the Hundred Days: a period of dramatic accomplishment and transformation.

The “hundred days” term originally came from Napoleon's time, when he escaped his exile, rallied the French army, and briefly retook power until he was defeated at Waterloo.

It was after 1933 that the term entered into widespread American usage and became a benchmark for presidential achievement. That year, Franklin Roosevelt took office amid unprecedented crisis. Not only had Herbert Hoover’s laissez-faire ideology failed to pull the nation out of the Depression, but in the winter of 1932–33, banks were failing at an alarming rate. With his first-ever fireside chat, an executive fiat declaring a bank holiday, and the quick passage of banking reform, FDR ended and reversed the run on the banks that had been threatening to make a dire economic situation worse.

The incomparable sense of urgency muted serious political opposition, creating a situation that was practically unprecedented in presidential politics. When FDR called Congress into session five days after his inauguration to pass his banking legislation, House Republican leader Bertrand Snell urged his party to vote yes—despite not having read the bill. “There is only one answer to this question, and that is to give the president what he demands,” he said. It sailed through the House unchallenged; no vote was recorded. The Senate passed it 73-7.

The banking legislation was just one of dozens of achievements of Roosevelt’s first hundred days. From the Civilian Conservation Corps to the National Industrial Recovery Act, from new public works programs to emergency relief, 15 major bills were signed into law. That itself was a staggering feat, but FDR did still more: the historic departure from the gold standard; the creation of federal bodies like the Tennessee Valley Authority and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; and dynamic new leadership expressed most famously through his fireside chats.

A quickie book published in early July dubbed this period “The World’s Greatest Ninety- Nine Days.” But in a fireside chat on July 24, the president replaced that label with his own. He spoke of “the crowding events of the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.” The phrase appeared in headlines the next day and caught on.

It’s essential to realize that the conditions that enabled Roosevelt’s flurry of achievement were so rare as to make his record irreproducible. Subsequent presidents and the journalists who covered them seldom highlighted the uniqueness of that historical moment. Instead, they typically inflated the importance of the hundred-day marker and angled for short-term publicity victories, however uncertain their long-range impact.

Thus, in the weeks before Dwight Eisenhower’s inauguration in 1953, Washington bristled with chatter about what his first hundred days might achieve. Pundits noted that Ike enjoyed not only Republican majorities in both chambers of Congress but also vast trans-ideological support among the electorate—entering office, the Washington Post noted, with “more favorable legislative auspices” and “a deeper reservoir of bipartisan goodwill” than any president since FDR. When the fateful date rolled around, the reviews were disappointing. Arthur Krock of the New York Times cited the president’s “slow start” marked by “miscalculations of timing and interpretation.” In the long run, however—indeed, even by 1956, when he ran for and won reelection—evaluations of Eisenhower’s presidency completely ignored his halting start.

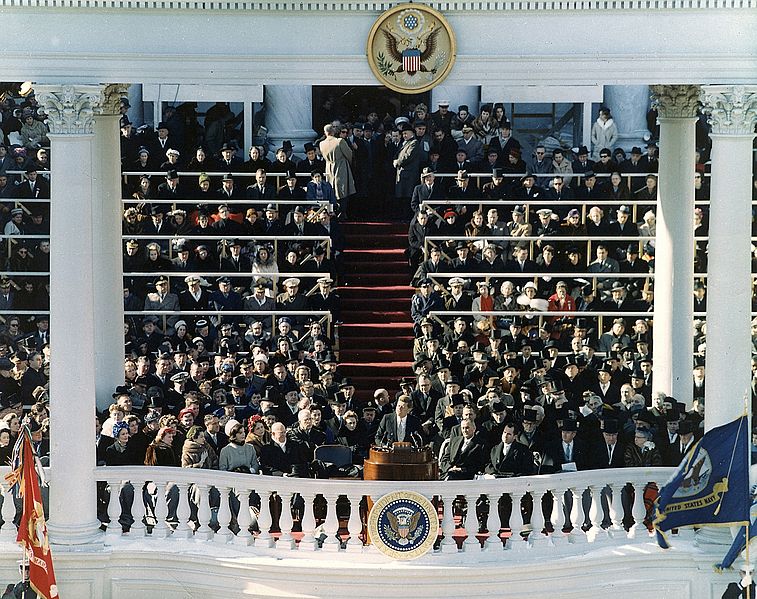

By John F. Kennedy’s presidency, talk about the first hundred days had become, in the judgment of historian and Kennedy aide Arthur Schlesinger, a “trap.” Kennedy griped about the pressure to work magic in those early weeks. “I’m sick and tired of reading how we’re planning another ‘hundred days’ of miracles,” he said to his chief aide, Ted Sorensen, as they drafted the inaugural address. “Let’s put in that this won’t all be finished in a hundred days or a thousand.” The result became classic and might well be engraved on an Oval Office wall:

President John Kennedy's Inaugural Address dismissed the 100 days timeframe and instead noted how long it would take to accomplish his goals.

All this will not be finished in the first one hundred days. Nor will it be finished in the first one thousand days, nor in the life of this Administration, nor even perhaps in our lifetime on this planet. But let us begin.

Nonetheless, if Kennedy hoped to lessen expectations, he failed. Sorensen was enlisted to draft a memo showing how Kennedy’s accomplishments stacked up favorably next to those of Harry Truman and Eisenhower.

The pressure did not abate. In 1965, Lyndon Johnson enjoined his congressional liaison, Larry O’Brien, to “jerk out every damn little bill you can and get them down here by the 12th.” Then, the president said, “you’ll have the best hundred days. Better than he did! . . . if you’ll just put out that propaganda . . . that they’ve done more than they did in Roosevelt’s hundred days.” Richard Nixon thought similarly. A clutch of his advisors formed a “Hundred Days Group” to sell the idea that his administration was a hive of activity, while trying, as he said, to get him “off the hook on quantity of legislation being the first measure of success of the first hundred days.” No presidents since have been indifferent to such concerns.

Presidents ought to realize that getting caught up in the hundred days deadline sets them up for failure. Like Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak, FDR’s burst of accomplishment— made possible not just by his distinctive political gifts but also by the exigencies of the Depression—is unlikely to be equaled. They ought to bear in mind as well that early accomplishments are not always the enduring aspects of a president’s legacy. Some of the most highly touted policies of Roosevelt’s Hundred Days fizzled: the National Industrial Recovery Act was invalidated by the Supreme Court, while a course of fiscal austerity was repudiated. In contrast, it was later in his presidency that Roosevelt signed into law such historic measures as Social Security, unemployment insurance, the right to collective bargaining, and the federal minimum wage.

Certainly, presidents need to plan carefully to take advantage of the brief honeymoon that they enjoy following their inauguration. Sometimes that period can present a chance to pass legislation that will prove elusive once the opposition finds its footing. But the focus should be on policies and legislation that can lay the groundwork for a propitious environment and long- term gains.

Two examples may suffice: Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton. Though possessed of diametrically opposed ideological orientations, they were comparably eager to set the nation on a new direction, based on a fundamental reconception of how the government collected and spent its funds. Both men ran for president amid economic hard times, touting new visions of economic renewal in their campaigns; both engaged in serious pre-inauguration planning in order to launch economic programs early on; and both weathered short-term bouts of unpopularity to see their plans pay off with both economic recovery and, in time, reelection and sustained popularity.

Reagan famously ran on what came to be called Reaganomics: deep reductions in domestic spending along with supply-side tax cuts that he believed would stimulate the economy following the stagflation of the Jimmy Carter years. Significantly, his team began planning how to implement it even while his campaign was still in full swing. Reagan’s campaign manager, the pollster Richard Wirthlin, deputized his aides David Gergen and Richard Beale to study how presidents from FDR onward had fared in their opening days, hoping to discern lessons for the incoming administration. Carter, for example, had capitulated to the media’s expectation of a headline-filled hundred days, but that goal was shortsighted. As Gergen told Reagan biographer Lou Cannon: “The main theme that came through was that Carter had engaged in a flurry of activity. There had been a blizzard of proposals that had gone to the Hill, but there was no clear theme to his presidency.” Focus, Beale and Gergen concluded, was indispensable.

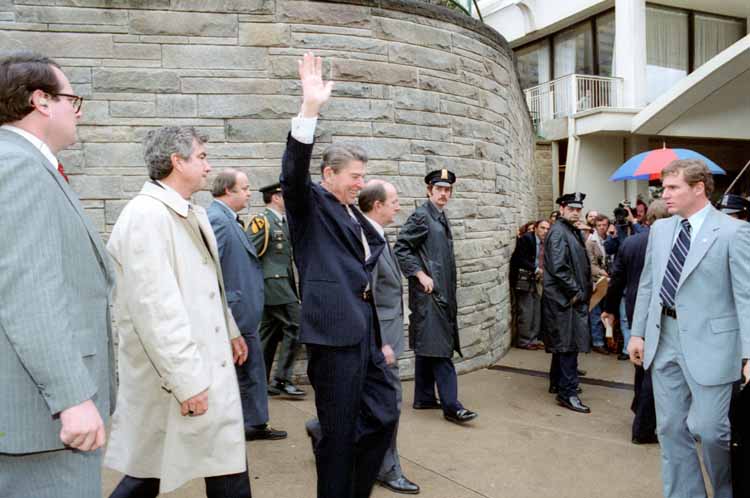

After President Reagan was shot during an assassination attempt in 1981, he was able to persuade Congress to pass his budget bill.

Dubbed the “Initial Actions Project,” the Beale-Gergen undertaking yielded a 55-page report of recommendations on how the White House should expend its energies. In December, aides laid out the key findings for the president-elect at Blair House. “We ought to have three goals,” summarized James A. Baker, a ruthless political operative who would wind up as chief of staff, “and all three of them are economic recovery.” This tight focus disappointed the social and religious conservatives who had helped give Reagan his victory, but the decision generated little dissent internally.

The unblinking attention to overhauling the budget was necessary to secure its passage, but it wasn’t sufficient. In fact, Reaganomics might well have died in the Congress had not the deranged gunman John Hinckley critically wounded the president outside the Washington Hilton in March. The ensuing flood of sympathy buoyed Reagan’s approval ratings. The next day, Treasury Secretary Donald Regan went on TV, where, borrowing a famous Reagan movie line, he urged Congress to “win one for the Gipper” by passing the budget bill. At a subsequent Blair House strategy meeting, Gergen proposed that Reagan stage his triumphant return from the hospital by calling for his plan’s passage before a joint session of Congress. Reagan did just that, delivering a speech that caused even Democrats to marvel and brought much of the opposition around. The radical tax-cutting measure, once deemed a long shot, passed easily into law.

The bill was historic for multiple reasons: Most immediately, its elimination of many tax brackets, including the top tiers, ratified and encouraged the rising anti-tax sentiment across the country. As a matter of public policy, it remains controversial, credited by supporters with boosting economic growth but blamed by critics for exploding the budget deficit and crowding out investment opportunities in the long run. Perhaps most important, it defined not only the Reagan presidency but indeed contemporary conservatism for a generation afterward.

Like Reagan, Bill Clinton won election against a failed incumbent. Running during economic hard times, he offered a recovery plan that, like Reagan’s, was not just a list of policies but a full-fledged economic vision. Clinton’s vision was the polar opposite of Reagan’s: restoring progressive taxation (instead of curtailing it); investing in infrastructure and research and development (instead of paring it) to meet the new challenges of an emerging global economy. During the campaign, Clinton promised to “focus like a laser beam on this economy,” and before his inauguration he convened an economic summit to survey the particular challenges, hearing testimony from a wide range of experts.

President Clinton with Vice President Gore worked hard to pass his budget bill during his first year in office.

A series of controversies early in Clinton’s term diverted the news media’s focus from economics and required White House attention. These controversies ranged from difficulties with key cabinet appointments to sideshows like the debate over whether to let gays serve in the military, to pseudo-scandals such as the replacement of personnel in the White House travel office. At the time, these episodes loomed large and seemed to betoken a troubled presidency. But the White House, despite considerable dysfunction, forged ahead with adapting Clinton’s campaign plans from the previous year into a budget bill, reckoning with the reality that the budget deficits that had been mounting through the presidencies of Reagan and George Bush, Sr., had turned out to be even more dire than projected.

At the hundred days mark, Clinton’s prospects did not look bright. Yet just a few months later, he secured his plan’s passage, by one vote in the House, and with Vice President Al Gore’s tiebreaker in the Senate. The bill was perhaps the most important of Clinton’s presidency. It began the process of retiring the deficit, and by his final years in office the nation was running budget surpluses for the first time since 1969. The bill also restored a measure of fairness to the tax code, raising the top bracket and expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for those of low income. And it began a multiyear pattern in which the White House wrought major change not through banner new laws but through quiet but consistent victories in the budgeting process. Just as Reagan’s economic vision lasted into the presidencies of both George Bushes, so Clinton’s was emulated by Barack Obama.

Though Clinton and Reagan promulgated very different economic visions, both succeeded on their own terms. Whatever lip service their administrations paid to the hundred days marker, they recognized that it was infinitely more important to develop and pass a budget bill that would not just promote recovery but set a new ideological direction for the country. They understood that the work that goes on in the White House communications office toting up laws passed and orders issued is in the end far less important than the work that goes on in forging the economic direction of the country, influencing what writers will say not in one hundred days, nor even one thousand, but over the lifetime of the administration and afterward.