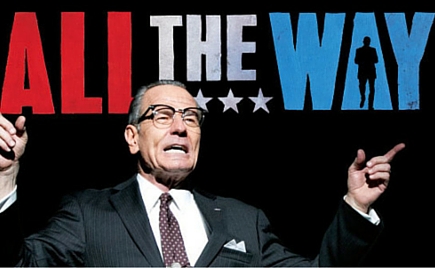

HBO’s “All the Way” a striking portrayal of Lyndon Johnson’s First Year

HBO’s All the Way, which airs for the first time on May 21, is a remarkable historical drama. Adapted by Robert Schenkkan from his Tony Award winning play, All the Way features Bryan Cranston as President Lyndon Baines Johnson. Cranston provides, by far, the best on-screen depiction of LBJ to date. Although he does not bear a particularly close physical resemblance to the Texas politician, Cranston fully inhabits the role and captures LBJ’s particular essence in all its complexities, contradictions, and insecurities.

More than that, Cranston captures the tragic dimensions, personal and political, of Johnson’s desperate need for approval and even love, and he emphasizes how this profoundly human characteristic of an often hard and even brutal man ultimately shaped the Johnson presidency.

Shenkkan’s script and Cranston’s performance accomplish this without over-simplifying Johnson or unnecessarily condemning or romanticizing him. Since viewing the film, I’ve been trying to think of a better film portrayal of any president but have yet to come up with one. (Suggestions from readers encouraged!)

All the Way begins at Dallas Parkland Memorial Hospital in the immediate aftermath of President Kennedy’s assassination and traces Johnson’s momentous first year in office, following key events such as the passage of the Civil Rights Act, the murder of three young Civil Rights workers in Mississippi, the Gulf of Tonkin resolution (giving Johnson congressional authorization to escalate the war in Vietnam), and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party’s demand to be seated at the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City.

All the Way concludes with Johnson’s landslide 1964 election victory, with Johnson at a post-election party at the LBJ ranch, silently contemplating how many of those celebrating his victory will turn on him at the first hint of weakness: “They will gut me like a deer.”

Throughout, the film foreshadows how the Vietnam conflict will eventually destroy Johnson’s presidency, despite his important and wide-ranging accomplishments.

Cranston is supported by a cast that delivers a series of first-rate performances portraying central figures of the era. Anthony Mackie’s Martin Luther King is a powerful counterweight to Cranston’s LBJ (and at least the equal of David Oyelowo’s King in last year’s Selma), while Joe Morton, Mo McRae, Marques Richardson, and Dohn Norwood, respectively, portray NAACP president Roy Wilkins, SNCC activist Stokely Carmichael, Freedom Summer leader Robert Moses, and King adviser Ralph Abernathy, key Civil Rights figures both working with and increasingly challenging King. The scenes in which the group debate strategy for the Civil Rights bill and then the Democratic convention are among the strongest in the film.

Melissa Leo, Bradley Whitford, and Frank Langella offer convincing performances as Lady Bird Johnson, Senator and Vice Presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey, and segregationist Georgia Senator Richard Russell, respectively. The film slightly overstates Humphrey’s relationship to Johnson during the lead-up to the Civil Rights bill. Although they worked closely together, Humphrey remained very much an outsider during this period.

Also notable is the emphasis that the film places on LBJ’s relationship with his long-time aide Walter Jenkins (played by Todd Weeks). Jenkins becomes the vehicle for the president’s desperate need for human connection but also unquestioning loyalty—a core relationship that painfully unravels just weeks before the election when Jenkins is arrested in a Washington men’s room on suspicion of homosexual activity, and Johnson refuses to have any further contact with him.

Interestingly, another close Johnson aide during the period, Bill Moyers, is not mentioned in the film.

Significantly for the Miller Center, Schenkkan’s script appears to rely on the LBJ recordings for inspiration (among other sources). The film includes multiple scenes of LBJ on the telephone, many of which seem to be based in part on actual, recorded calls. A highly speculative list of recordings that might have shaped the script include the following telephone calls.

- A post-assassination call to King.

- A tense, confrontational call to Mississippi’s segregationist governor Paul Johnson after the disappearance of the Civil Rights workers appears to be drawn in part from a series of conversations between the two, as well as from a conversation between LBJ and Mississippi Senator James Eastland in which the latter suggested the disappearance might be a staged publicity stunt.

The film includes a dramatic phone call from LBJ to Georgia Governor Carl Sanders on the floor of the Atlantic City convention. Sanders reports that the southern states will walk out of the convention if Johnson enforces a proposed compromise that would seat two MFDP members. The Governor, a relative moderate among southerners and a Johnson ally, suggests that he too will probably walk. The scene ends with LBJ appealing to Sanders’ sense of morality, ethics, and decency before slamming the phone down in intense frustration and despair. After Lady Bird rebuts LBJ’s petulant threats to quit and go back to Texas, Walter Jenkins reports that Sanders has announced that he will not walk out. Dialogue in the dramatic conversation appears to be drawn in part from two calls that LBJ made to Sanders during the convention. But Sanders was not on the convention floor at the time of the calls, both calls ended cordially.

Other conversations, conducted in person in the film, may also be drawn from recorded telephone calls: one example is a scene in which LBJ appeals to Senate Minority Leader Everett Dirksen’s sense of history as he successfully lobbied for the Illinois Republican’s support in bringing moderate Republicans into an effort to end the Southern filibuster of the Civil Rights bill. The conversation echoes this recorded phone call between LBJ and Dirksen, which actually occurred after the cloture vote.

Incidentally, LBJ was right—Dirksen’s historical legacy and reputation today rests entirely on his decision to work with LBJ in bringing the bill to fruition.

All the Way is a must see for anyone interested in the 1960s, the civil rights movement, or the Johnson presidency.