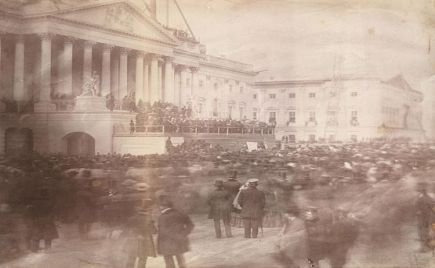

First Words: James Buchanan, March 4, 1857

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

“To the Patriot Buchanan / The tribute we owe, / Til the people proclaim it again to bestow, / And the fourth day of March be again made to yield, / A harvest of Glory in Liberty’s field.”

-Col. W. Emmonn, an Ode composed in honor of James Buchanan’s inauguration

History has not been kind to James Buchanan. Historians in the business of ranking presidents generally place him near the infamous bottom of the list - beyond the relative harmlessness of being completely unknown (Millard Fillmore) and sometimes even the disgrace of scandal (Warren G. Harding). Arguably, he his lowly rank is, in part, due to his proximity to the near-universally accepted “best” president, Abraham Lincoln. The contrast does not serve Buchanan’s legacy well. To summarize his historical portrait: he is the president who believed that the South had no right to secede from the Union, and that the president had no right to stop them. Not surprisingly, his inaugural address gets very little attention from presidential scholars. While there is no use in arguing for renewed attention to Buchanan, it is worth noting that the inaugural addresses of “failed” presidents are at least as interesting as those of successful ones.

At the time, Buchanan’s inaugural did not enjoy a warm reception. The front page of the New York Times featured the speech the next day, together with an article entitled “Narrow Escape of the President Elect from a Violent Death,” which included unflattering details of Buchanan suffering from diarrhea as a side effect of accidental arsenic poisoning. Even more recent, evenhanded, considerations of Buchanan and his inaugural add only slight modifications to his “reviled” legacy. “James Buchanan,” writes Michael Carrafiello of Miami University, “was tragically ill equipped to become the nation’s chief executive at a time of burgeoning crises.”

The speech lives up to expectations, though it can be read two ways. It can be read as the best attempt of an incoming president to serve as an arbiter in a time of growing sectional conflict, or it can be read as a tragic miscalculation of an inept president-elect.

As for evidence in support of the first reading, Buchanan saw abolitionists as a group of agitators who, if not relegated to the fringes of political life, would incite civil war. “May we not [...] hope,” Buchanan questioned, “ that the long agitation on this subject is approaching its end, and that the geographical parties to which it has given birth, so much dreaded by the Father of his Country, will speedily become extinct?” His specific invocation of George Washington is telling - for it was Washington who famously warned of the dangers of political parties. Buchanan, in advocating for the suppression of “agitators” seeking the end of slavery, is not so different from moderates whose goal was the preservation of the Union.

This, of course, inevitably encounters the points made in the speech in which Buchanan seems to have completely miscalculated the direction of the country, providing evidence for the second reading. He begins by talking about the turbulence of the previous election, concluding that , “when the people proclaimed their will, the tempest at once subsided and all was calm.” He believed the question of slavery would be settled by the Supreme Court: “it is a judicial question, which legitimately belongs to the Supreme Court of the United States, before whom it is now pending, and will, it is understood, be speedily and finally settled.” The Dred Scott decision, the pending case Buchanan refers to, did not settle the question of slavery, it further impassioned the “agitators” that Buchanan feared. He goes on to say, “most happy will it be for the country when the public mind shall be diverted from this question to others of more pressing and practical importance.” While the precise causes of the Civil War are a matter of historical argument, the war itself can be cited as evidence that Buchanan may have downplayed how “pressing” and “practical” the question of slavery was.

Examining the inaugural address does not provide any information that would vindicate Buchanan from the annals of failed political leaders - and it shouldn’t. However, that does not mean it is justifiably ignored or substanceless. In the context of other inaugural addresses, it is a reminder that Presidential inaugurations inevitably become spectacles of profound foreshadowing and dramatic irony. They are the vital frames through which, we view the terms of past presidents.