First Words: Rutherford B. Hayes, March 4, 1877

Rutherford Birchard Hayes is perhaps one of the most underappreciated presidents (CSPAN historians rank him 33rd). Although he ascended to the presidency in one of the most contested and controversial elections, “Rud” was an intelligent man and honest man who sought to reform the federal government even the face of a hostile Congress and in an era of Congressional dominance.

One of the priorities of President Hayes was to reform the system of civil service appointments, which had been based on a spoils system since the presidency of Andrew Jackson. Rather than doling out federal jobs to political supporters, Hayes called for awarding jobs based on merit. Hayes’ civil service reform success, even if it was limited, was significant for a couple reasons. First, Hayes’ efforts set “a significant precedent as well as the political impetus for the Pendleton Act of 1883,” which was signed into law by none other than President Chestur A. Arthur. Second, in a period marked by Congressional dominance, Hayes restored the President’s constitutional power of appointments. While Congress could suggest those whom they thought should be nominated for federal jobs, by the end of the Hayes administration, senators and congressman no longer dictated these appointments to the president.

Hayes laid out his civil service reform agenda in his Inaugural Address on March 5, 1877:

I ask the attention of the public to the paramount necessity of reform in our civil service--a reform not merely as to certain abuses and practices of so-called official patronage which have come to have the sanction of usage in the several Departments of our Government, but a change in the system of appointment itself; a reform that shall be thorough, radical, and complete; a return to the principles and practices of the founders of the Government. They neither expected nor desired from public officers any partisan service. They meant that public officers should owe their whole service to the Government and to the people. They meant that the officer should be secure in his tenure as long as his personal character remained untarnished and the performance of his duties satisfactory. They held that appointments to office were not to be made nor expected merely as rewards for partisan services, nor merely on the nomination of members of Congress, as being entitled in any respect to the control of such appointments…

The President of the United States of necessity owes his election to office to the suffrage and zealous labors of a political party, the members of which cherish with ardor and regard as of essential importance the principles of their party organization; but he should strive to be always mindful of the fact that he serves his party best who serves the country best.

As president, Hayes asked Secretary of Interior Carl Schurz and Secretary of State William M. Evarts to head a cabinet committee to draw up new rules for federal appointments. However, Hayes’ reformist agenda ruffled the feathers of leaders in his own Republican Party. With a Congress obstinate to civil service reforms, President Hayes issued an executive order on June 22, 1877 prohibiting political assessments and forbade the management of political parties, conventions, and campaigns by civil servants. While Hayes did not want to destroy Republican Party organizations, he did want to depoliticize the civil service. However, arguing that Hayes was destroying their organizations, Republican leaders in Congress simply ignored the executive order.

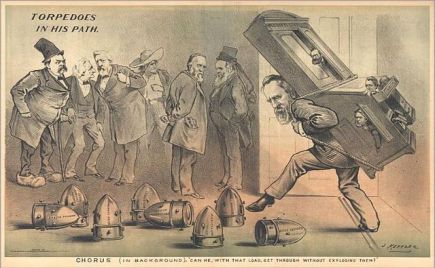

Hayes responded by going after one of the chief flouters of the order, Senator Roscoe Conkling of New York. Hayes decided to remove Chester A. Arthur, the collector of the Port of New York who ran the New York Customhouse. Although Arthur was a reasonably efficient administrator, he kept the Customhouse (with Conkling’s approval) in politics. The Customhouse collected some 70 percent of the nation’s revenue and was the largest federal office at the time. With the Customhouse operating as “a center of partisan political management,” it was the perfect target for Hayes to make his political point. Hayes demanded Arthur’s resignation and that of his subordinates and submitted three of his own nominees to the Senate to replace them. After the Senate unanimously rejected his nominees, Hayes waited until July 1878 to remove Arthur and others and replaced them with his own recess appointments – Edwin A. Merritt and Silas W. Burt. Although the Senate once again attempted to block Hayes’ nominees when it reconvened in January 1879, enough Republicans joined with Democrats to make Hayes victorious. Burt was charged with ensuring that the New York Customhouse was a showplace for reform. Indeed, appointments at the Customhouse were made thereafter based on merit following open competitive examinations.

On a more limited scale, Hayes also went after the “star route” rings, a system of corrupt contract profiteering, in the U.S. Postal Service at the request of Interior Secretary Schurz and Senator John Logan. Hayes stopped granting new “star route” contracts, but didn’t end existing contracts.

Throughout his presidency, Hayes was a strong advocate for reform. While legislation did not pass during his presidency, from his Inaugural Address to his final message to Congress on December 6, 1880, Hayes continued to press Congress to enact permanent civil service reform. Hayes, however, was successful insofar as his efforts were a major factor in the passage of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act of 1883 and regaining the power over appointments to the presidency.