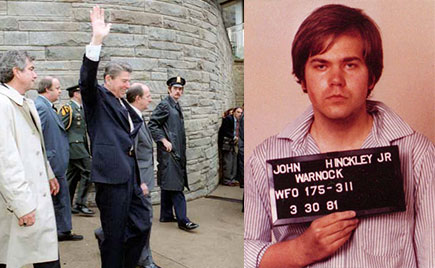

The attempted Reagan assassination

On March 30, 1981, fewer than 100 days into President Ronald Reagan’s first year in office, John Hinkley Jr. attempted to assassinate the president outside the Washington Hilton Hotel. Reagan was injured by a single bullet, and through the Miller Center's Ronald Reagan Oral History Project, members of his administration recall their thoughts and experiences that day.

RICHARD V. ALLEN: Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs

Anyway, so I said, “Mr. President, we’re having a national security briefing today,” and he said, “Okay” [low weak voice] so weak. I said, “There it is, and you’ve had your national security briefing, congratulations, Mr. President.” Deaver was in the room, I forget who else was in the room.

And he said, “Wait a minute, wait a minute, what’s that in there?” And I had a big stack of these cards. He said, “What’s that?” I said, “These are cards from the kindergarten class of Oakridge Elementary School in Arlington, Mr. President.” He said, “Let me see them.” I handed them over and he started to go through them, one by one. He went through, read every card. There must have been 25 cards in there. So he said, “Which one’s your daughter’s?” I said, “It’s one that’s in there.” So that was the card that she had written. She wrote two actually, and then she wrote this one, “Dear President Reagan, get better.” So he said, “Give me your pen.” . . .

[The Miller Center’s] Russell Riley: [reading] “President Reagan, Please get better, Love, Kim Allen.” And then, in his handwriting below: “Dear Kim, forgive me for using your card for my answer, but I wanted to let you know how very much I appreciate your good wishes and your lovely card, Love, Ronald Reagan, April 15, 1981.”

MARTIN ANDERSON: Assistant to the President for Policy Development

There’s all kind of thinking that goes on. There have been books, a Stanford professor wrote a book about this. There are a few—I’ll be semi-charitable—but there is an academic view of what should happen. Basically the academic view is, you’ve got the President in charge, he’s in control. Something happens to the President, who’s in control and who’s in charge? Wrong, that’s not the way it works. It is not like throwing a light switch.

I think what happened that day is probably a clearer example of it. When we got the information that he had been shot, we did not know the seriousness of it. We did not know if he was dead, we didn’t know how wounded he was, we just knew he had been shot. Now, what happened was, and no one can seem to understand this is—nothing. You wait. You find out what the situation is. You don’t rush off and assume, “Oh my God, he’s been shot, we’re going to put the Vice President in charge.” Or you don’t say, “Well, he’s been shot but he’s in charge so let’s talk to him and see what he is going to do.” You wait and say, “Well, let’s see what happens.” And people were very calm and they just settled down.

It is amazing how much goes on in the government, in the White House, without someone “controlling” it. It works, people do things. Life proceeds. They were just very careful. They took slight steps, they checked to make sure this wasn’t an overall plot. They checked to see where the Soviet submarines were and the Soviet submarines were a little bit out of their normal course and closer to our shores than they were supposed to be, so they checked that out. Then a little while later they said, “Well, that’s not a problem”—and there were more submarines, and they said, “Wait a minute, what’s going on here.” Then they discovered it was the end of the month and that actually they were changing battalions and so they had more submarines, there were always more submarines. They didn’t act precipitously and the academic mind can’t understand that.

In terms of his policies, there was no change at all. He had been working on these for a long time; they were set in place. We knew what he wanted to do. He basically had laid it all in place and we just proceeded to try to get it done, but he never changed any policies that I saw.

MAX FRIEDERSDORF: Assistant to the President for Legislative Affairs

I went over to GW hospital, and went up to the President’s room, and Jim was outside the room with Mrs. Reagan and her secret service agent there and Jim said, “Max, I want you to stay here until I tell you to leave.” I didn’t understand. Mrs. Reagan was all upset, of course. He said that Senator [Strom] Thurmond had come over to the hospital and had talked his way in, past the lobby, up to the President’s room—he’s in intensive care, tubes coming out of his nose and his throat, tubes in his arms and everything—and said that Strom Thurmond had talked his way past the secret service into his room and Mrs. Reagan was outraged, distraught. She couldn’t believe her eyes.

He said, “You know, those guys are crazy. They come over here trying to get a picture in front of the hospital and trying to talk to the President when he may be on his deathbed. You stay here until I tell you to leave. If any Congressman or Senator comes around here, make sure the secret service doesn’t let anybody up, even on this floor.” So I stayed there for about three days, four days, until he came out of intensive care.

He stayed in the hospital about ten days. Other members came later, a very, very few. Howard Baker came. I think Mrs. Reagan made an exception with Tip and probably Howard Baker—those are the only two I can remember when I was there.

Then I think he went home after ten days, but he couldn’t come downstairs in the White House. He stayed up in the residence for a long time recuperating. So we’d have to have meetings up there. Bless his heart, he’d be riding an exercise machine trying to get his strength back. He’d have a pair of jeans on with a T-shirt. He was about 70 then, maybe 71. He had a physique like a 30-year-old muscle builder—he really had big shoulders and chest, and I think his physical condition saved his life. He was up there lifting weights and riding the bike, trying to get built back up. Incredible constitution. It wasn’t too long before he was back in the office, going about his business. I wouldn’t have believed it if I hadn’t seen it.

KENNETH KHACHIGIAN: Chief Speechwriter

I went down to the situation room where that famous scene between Al Haig and Cap Weinberger happened, and then I followed Haig back up to the briefing room when he said he was in control. Quite a day. Then the White House just went into this sort of quiet period. The President came out of danger, and we didn’t have the same urgency in the process. It gave us all time to organize a little more and get caught up. The President, of course, survived the shot. I can’t remember how many days he was in the hospital. Then he came back. But we had lost Jim Brady, basically, because he had severe brain damage. That was a big loss, because Jim was very, very likable, was a great personality around the White House and was a great press secretary. He was given a little bit to being flippant and whatnot, but the press liked him a lot. That was a really big loss.

The security changed, obviously, became stricter. There was a period of time between the President’s shooting and then later on the bombing of the barracks in Beirut, and then they finally shut off Pennsylvania Avenue. But not right afterwards. I don’t think there was a big change. The White House slowed down a great, great deal, and there was a lot of focus on just waiting for the President to get well. But I can’t tell you that there were any big changes.

JAMES C. MILLER: Director Office of Management and Budget

We were in the Roosevelt Room, meeting about the next steps in the regulatory relief effort. We literally walked out of the Roosevelt Room and a lady comes out of the press office, screaming to the deputy press secretary, Larry Speakes: “Larry, Larry, the President has been shot at and Jim Brady has been shot!” It was pandemonium there, but it was controlled pandemonium. There were some reports later. They said we knew the President had been shot, it was serious and this and that. Not true. I was there.

[Dick] Darman picked up the phone immediately and asked for “Signal,” which is the White House military switchboard. “What’s going on?” About that time Jim Baker arrived. Baker grabbed the phone from him, and said, “I don’t understand this. If he’s fine, if he’s okay, why are they going to GW [George Washington University] Hospital? I don’t understand this.” Out of the corner of my eye I saw [David] Gergen running across. He had Meese in tow and then [Michael] Deaver came running in. They threw the phone down, ran, jumped in the car—they’d brought the car around front—and took off for GW.

The notion that they knew all along that something was seriously wrong is not correct. They found out when they arrived at the hospital, but they didn’t know in that immediate response. But the President was quite ill. It was a life-threatening thing. . . . the assassination attempt was a big setback. When I met with the President a few days later, I was really alarmed at how weak his voice was.

LYN NOFZIGER: Assistant to the President for Political Affairs

I went into the emergency room, and I ran into one of the advance men there. I said, “You know, you ought to be taking notes, and you ought to go home and get a tape recorder and talk all this into a tape recorder, because this is going to be historical.” I don’t know whether he ever did or not, but I grabbed some pieces of paper from the nurses’ station there, the forms with the blanks.

And I began jotting down notes, these things that Reagan had said—or it was reported to us that he said—such as to Nancy, “On the whole, I would rather be in Philadelphia.” Paul Laxalt had come over, so there was Meese— Oh, and we had sent Speakes back to the White House to handle the press there, which was proper. Somebody had to be there. It was decided that he would do that, and I would handle the press at the hospital.

So Laxalt and Meese and Baker and I are standing there, and they bring Reagan out of this little emergency room where they’ve had him, and they’re going to take him into the operating room. As they wheel him by on the gurney, he says— Baker said he winked at me. I never saw him wink, but I’ll take that. Reagan did say, “Who’s minding the store?” I learned later, of course, that the doctors had cut his suit off of him. Now, Reagan’s kind of a tightwad, and he was just furious, “You’re ruining my suit.” To hell with the fact that I’m dying, you’re ruining my suit.

He told Deaver after he was shot that he felt that God had saved him for a specific purpose, and that he would try to remember that. I think he thought that that purpose was to stand up to and get rid of communism, because he certainly became determined.

STUART SPENCER: Campaign Strategist

The only change I saw—he had an energy level problem for a while coming back. He almost died. There was a big change in her. She was scared to death after that. She even lobbied not to run again. She had real qualms. If she asked me once, she asked me fifteen times whether he should run again or not. It wasn’t the fear of winning or losing. Every time he went out after that, she had a fear of him getting shot. Why did she talk to Joan Quigley and all these astrologers? She was looking for help. She might have gone in to see the priest to try to get help. It was that sort of a grasp. You and I can understand it. He was very fatalistic about it, but she was scared to death. Big change in her.

CASPAR WEINBERGER: Secretary of Defense

I had responsibilities, and I felt that I should exercise them. I didn’t know what the Soviets were doing, what the nature of this attack had been—whether it was a single madman, or whether it was some sort of concerted effort. I even had in mind the [Abraham] Lincoln assassination, where there was a concerted effort, and several of the members of the Cabinet—including the Secretary of War—had been attacked the same night. I felt that the troops should have a higher degree of alert and be ready for anything that might occur, even though, fortunately, it did not. It was the work of a single madman.

They had to work their way through that to get down to get this bullet. He said it was incredible, the physical development and the strength that was there. Getting an explosive bullet out under any circumstances is a reasonably hazardous enterprise, but his recovery was very complete and very quick—amazingly quick—although I didn’t think it was going to be. I saw him a couple of days after the operation, and he looked completely deflated. I thought it would be months or years before he would ever be able to regain his capabilities. It was a matter of a few weeks.