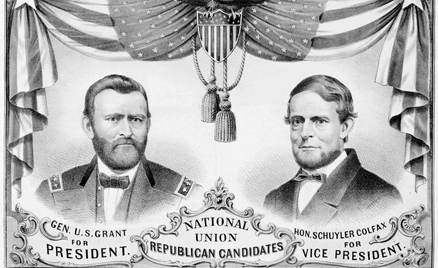

The “General” Election: Ulysses S. Grant (1868)

In 2016, voters and analysts talk about the importance of pre-White House experience and speculate that military experience would provide an advantage in national security issues. The “General” Election is a four-part blog series examining how George Washington, Zachary Taylor, Ulysses S. Grant, and Dwight Eisenhower, all career generals, won the presidency and how effective they were once in office.

1868 Margin of Victory

Electoral College: Grant, 214; Seymour, 80

Popular Vote: Grant (Republican), 53%; Seymour (Democrat), 47%; 309,584 vote differential

------

Ulysses Grant never intended to go into politics. After graduating from West Point, he rose through the ranks of the army, going from second lieutenant to general. Having fought in both the Mexican War and the Civil War, Grant proved himself as a professional soldier. By 1864, Lincoln chose Grant to command the Union armies. In July 1866, Grant was promoted and became the first commander since Washington to hold the rank of general of the army, a five-star title.

Abraham Lincoln’s April 1865 assassination had left the country yearning for strong leadership, but his successor Andrew Johnson simply could not fill his shoes. Many believed that Johnson was unable to provide the type of direction that the nation needed during the tenuous and delicate Reconstruction era. Indeed, he faced impeachment and avoided Senate conviction by one vote.

Grant might not have had any ambition to occupy the White House, but fate had a different plan for him. While serving as general of the army and secretary of war, Grant took issue with what he saw as Johnson’s mismanagement of Reconstruction in the South. While Johnson aimed quickly to reunite the torn nation, he did so at the expense of protecting the rights of newly freed slaves. This led to a split in the Republican Party, where the Radical Republicans, Grant included, aimed to provide African Americans with civil and political rights. Grant ultimately refused to back Johnson’s struggle with Congress and was recruited by the Radicals for a presidential bid.

Despite maintaining that he never sought the presidency, Grant encountered an increasing amount of public pressure to run, and, in 1868, was named the Republican nominee without serious opposition. The Republican platform included support for black suffrage in the South, but still left autonomy for northern states to decide if and how blacks would be enfranchised. The campaign that followed was unusual by today’s standards. Grant, who ran against Democrat Horatio Seymour, did not actively campaign and made no public promises, instead relying on his popularity to win the presidency in 1868 with an impressive margin. It seems as though the nation, still reeling from the violence of the Civil War and the turmoil that followed it, craved the peace that Grant represented and the Republican Party promised. Undoubtedly, Grant’s popularity and biggest strength came from his record as a war hero.

However, Grant himself recognized after two terms in office that stepping into the White House without any political training had been his downfall as president. Although he eventually came to be recognized for his defense of civil rights, Grant is today consistently ranked in the bottom half of presidents. It seems as though the “outsider” status and distaste for politics that helped him win the presidency were ultimately his downfalls.

TAKEAWAY: Grant was able to secure the presidency largely because of his popularity as a Civil War hero. However, by his own admission, his aversion to politics and lack of political experience prohibited him from being as effective as he had hoped. Despite his experience as a leader in the army and ambitious goals in office, Grant’s presidency illustrates that the skills needed to enter office are not necessarily those needed to become an effective president. In an unusual twist, Grant’s post-presidential memoir, written as he battled cancer, is considered the best of its genre. Now in the public domain, the classic work can be found here.